PREFACE

I

am approaching the midline of the tenth decade of a charmed life, if

judged by the quality of lives seen in most of the world. In America

that is not the case, for freedom and opportunity exists to such a

degree that charmed lives are common. Most "best sellers" depict the

highly successful, as measured in power or wealth, and a traumatic

childhood. I, on the other hand, like so many others, had all of the

advantages of a concerned, loving, disciplined home in an upper middle

class world. Despite these advantages, I still became successful, but my

concept of success had nothing to do with power or wealth. It did

require a comfortable living. But above all, it demanded that, whenever

possible, I "give something back." I

am approaching the midline of the tenth decade of a charmed life, if

judged by the quality of lives seen in most of the world. In America

that is not the case, for freedom and opportunity exists to such a

degree that charmed lives are common. Most "best sellers" depict the

highly successful, as measured in power or wealth, and a traumatic

childhood. I, on the other hand, like so many others, had all of the

advantages of a concerned, loving, disciplined home in an upper middle

class world. Despite these advantages, I still became successful, but my

concept of success had nothing to do with power or wealth. It did

require a comfortable living. But above all, it demanded that, whenever

possible, I "give something back."

The story I try to tell is

studded with "give backs," a natural result of a mind set about which

little has been written. I didn’t recognize what this mind set was until

well into my retirement eighties, when my days and nights provided ample

time for a life’s review. One of my "give backs" was diminishing the

chance of a fatal pulmonary embolism with surgery or travel. Another was

making the weighing of patients routine to prevent fluid balance

mistakes, often fatal. A third introduced the catheter to keep

congenitally incontinent children dry and thus active, social

participants. A fourth altered kidney surgery to make it quicker and

less painful. Free time allowed my still fully active mind to keep

asking new questions. My one talk after War..at Oakland. Dad would have

me speaking to all the clubs and I said "no."

(Photo

left - My one talk after War..at Oakland. Dad would have me speaking to

all the clubs and I said "no.") (Photo

left - My one talk after War..at Oakland. Dad would have me speaking to

all the clubs and I said "no.")

And finally, there is the hope

that I have told of real life experiences, many humorous, but revealing

enough to let those not physicians in on our professional secrets. What

a wonderful trip this has been, as the memories preserved by my Process

Mind surface to be lived again and again, a practice that resulted from

my forays into areas that others had not tread. What did I see or just

stumble on, as I took a moment to notice what made me stumble? In so

doing, perhaps a hidden truth had surfaced? Then an answer appeared.

It

dawned on me that my inability to marshal a Quick Memory was in reality

a great blessing. I had considered this a deficit as I watched the

“straight A” students easily be accepted in whatever specialty they

chose to follow. My being admitted to medical school had required other

qualities than just getting top grades. Today, where sheer numbers

demand that machines replace human judgments, the personal element is

often lost. The paradox is that the Process Mind is needed everywhere

and more than ever. This type of mind has a peculiar need for mentors,

for its never-ending questions must be answered. I hope I can encourage

such minds to persevere. Thus I relate my own Process Mind story as one

of doing something every day for someone while fulfilling the commitment

to home and family. It

dawned on me that my inability to marshal a Quick Memory was in reality

a great blessing. I had considered this a deficit as I watched the

“straight A” students easily be accepted in whatever specialty they

chose to follow. My being admitted to medical school had required other

qualities than just getting top grades. Today, where sheer numbers

demand that machines replace human judgments, the personal element is

often lost. The paradox is that the Process Mind is needed everywhere

and more than ever. This type of mind has a peculiar need for mentors,

for its never-ending questions must be answered. I hope I can encourage

such minds to persevere. Thus I relate my own Process Mind story as one

of doing something every day for someone while fulfilling the commitment

to home and family.

My Process Mind works like this. I must

understand to remember. This takes more time than is required for the

Quick Memory minds. However, it is the remembering that makes the

difference, allowing me to tell this story today in the hope I will be

effective.

I

have come to believe that enthusiasm, call it a passion, is a catalyst,

unquenchable and indestructible, at times allowing one to accomplish

what seems impossible. The Process Mind is ideally suited for this

endeavor, for it demands basic truths to be stored and recalled.

Possibilities of new concepts and new uses fan out, requiring only solid

judgment as to their value and their doable potentials. I

have come to believe that enthusiasm, call it a passion, is a catalyst,

unquenchable and indestructible, at times allowing one to accomplish

what seems impossible. The Process Mind is ideally suited for this

endeavor, for it demands basic truths to be stored and recalled.

Possibilities of new concepts and new uses fan out, requiring only solid

judgment as to their value and their doable potentials.

Whom do I

hope will read this story? First will be high school students wondering

what is ahead, and how their journeys may be influenced by an

understanding as to how they learn and remember. Recognition of the

Process Mind and its characteristics can make all the difference, as

curiosities abound and mentors are sought and recognized. I would wish

to be one of them.

Their parents are next in line, especially the

new ones, searching for guidance as they direct young lives flowering

before them. It is critical that the "slower to remember" Process Minds

be recognized and stimulated early on.

I

hope medical educators will read here about how one of their own has

used his Process Mind to contribute solidly, and will recognize the

creative potentials lying in such minds as they not only leave

something, but stimulate fellow students to awaken their own processing

potentials. Surely, to have both a Quick Memory and a Process Memory

acting in concert is a gift with immense potential. It is likely to be

the process component that is the driver. At home and in the classroom,

a start at uncovering and stimulating the thinking potential of a child,

whether naturally a Quick Memorizer or Process Thinker, would be to

counter questionable statements with "Please explain." This would seem

to be well within the reach of the concerned parent. Would the modern

schoolroom make time for this exploration? Surgeons like myself can

relive experiences, perhaps even more poignant than my own, as I expose

the workings of our medical minds under trying circumstances. I

hope medical educators will read here about how one of their own has

used his Process Mind to contribute solidly, and will recognize the

creative potentials lying in such minds as they not only leave

something, but stimulate fellow students to awaken their own processing

potentials. Surely, to have both a Quick Memory and a Process Memory

acting in concert is a gift with immense potential. It is likely to be

the process component that is the driver. At home and in the classroom,

a start at uncovering and stimulating the thinking potential of a child,

whether naturally a Quick Memorizer or Process Thinker, would be to

counter questionable statements with "Please explain." This would seem

to be well within the reach of the concerned parent. Would the modern

schoolroom make time for this exploration? Surgeons like myself can

relive experiences, perhaps even more poignant than my own, as I expose

the workings of our medical minds under trying circumstances.

Retired

physicians as a group should, with a little time on their hands, chuckle

at events I have described, perhaps unearthing their experiences not

thought of for a long time and to be relished in the retelling and

hearing. And car lovers should share with me the joys of driving their

“Blue Beauties” and vicariously racing on a Bondurant Speedway. Retired

physicians as a group should, with a little time on their hands, chuckle

at events I have described, perhaps unearthing their experiences not

thought of for a long time and to be relished in the retelling and

hearing. And car lovers should share with me the joys of driving their

“Blue Beauties” and vicariously racing on a Bondurant Speedway.

Historians must not be left out, for much that is documented here will

reveal the characteristics of the part of America I represent, as it

chronicles one family’s trials and joys in a privileged century of

freedom, at times contested, but which in the end is a monument to the

America envisioned by founding fathers almost 250 years ago.

CHAPTER 1

THE BEGINNING

I was born

I’ve

been reading another success story. It is so wholesome that I wonder if

I would be reading it if the subject were not already a famous person.

Be that as it may, I will assume that someday, probably long after I am

gone, I could be a famous memory. So why don’t I tell my version as to

how I got there while I can still be put on the spot with questions?

First, let me make it clear that I was not raised in poverty, was not

mistreated, and have never thrown a punch in anger or as a defense. I

had what many could call an ''idyllic childhood" and yet I made good, if

personal satisfaction with how I have used my days is to be the judge. I’ve

been reading another success story. It is so wholesome that I wonder if

I would be reading it if the subject were not already a famous person.

Be that as it may, I will assume that someday, probably long after I am

gone, I could be a famous memory. So why don’t I tell my version as to

how I got there while I can still be put on the spot with questions?

First, let me make it clear that I was not raised in poverty, was not

mistreated, and have never thrown a punch in anger or as a defense. I

had what many could call an ''idyllic childhood" and yet I made good, if

personal satisfaction with how I have used my days is to be the judge.

I was born at home in Oakland. Albert Meads, to become "Uncle Bert,"

delivered me at 125 Grand Avenue in a day when hospital deliveries had

become almost the rule. He had been a family doctor for some years.

Then, as specialties began to appear, he went to the Midwest to train as

a urologist with one of the icons of that time. He returned, accredited

by this minimal specialty experience, yet his family practice habits

stayed with him until the day he died. He loved people. Bringing them

into the world was his apex of achievement.

I come into our

world at the end of World War I

As a tiny tot on Grand

Avenue I had no understanding that Dad was at death’s door. The 1918 flu

epidemic had taken him down as he worked in the Military Reserve. Uncle

Bert believed he had no chance to survive. The mortality was soaring

throughout America, taking far more American lives at home than did the

war itself. Dad somehow made it. Our family lives could again take off.

There was a family tenacity already manifest. This seems to have

trickled into the next generation, for I too was tried by whooping cough

(Pertussis) a few years later, in the days before immunization became

the rule. By then we had moved to Highland Avenue in Piedmont. I suppose

this was a step up on the social ladder.

Dad

did not mind the added distance to work. On the cushy seat of his Pierce

Arrow, he was never happier than when behind its wheel. This also turned

out to be a family characteristic as I inherited this joy, later pushing

it to extremes when I passed the Bondurant High Performance Driving test

60 years later. That story can wait.

Dad’s work–call it joy

Lyon Storage and Moving Co. was the first of its kind west of

the Rockies. Most of Dad’s vans were horse drawn. He would be on his way

at five o'clock each morning in order to supervise the harnessing and

make sure that hooves were healthy. Petro Pine ointment, a balsamic

salve, was his wonder drug. It went on every sore or abrasion. Its

quality of "clinging" made it work. Where did this come from? Some

entrepreneur had stored crates of it, and then disappeared, not to

return. Dad, always the opportunist, on this occasion got his full

money’s worth.

Dad thought he was a good judge of horses,

until he purchased one that turned out to be blind. A Lyon

characteristic again appeared as he made the best of a bad bargain. The

blind one became the center horse and the leader in the brace of three.

His power surpassed his fellows as he pulled the others with him.

Then, in our first Piedmont year, a motored van was acquired. It was

a flatbed with a top speed of 12 miles an hour. It could deliver loads

on Piedmont’s streets, so steep that horses feared to tread. Next came

the enclosed van, a bit faster. It rang the death knell for horsepower

not enclosed in steel. And finally, Dad acquired the tractor-trailer to

end up as an 18-wheeler.

Though Dad loved his horses, it was the

horsepower driving the pistons in his Pierce Arrows that thrilled him.

He told me that he had owned 17 Pierce Arrows in a row. When the models

came out in the twenties, still with cloth tops and celluloid side

curtains, he started to acquire these seven-passenger behemoths from

Piedmonter Eamon of “Eamon Olives.” He had paid $5,000 for each car with

its lifetime warranty. After only one year, the Pierce was barely broken

in. Soon Dad had a local company, Gillig, now a nationally known bus

company, put on the first closed top. It was of patent leather and with

sliding windows. These cars, with the life-sized lion from the office

window on the hood, led many a downtown parade, Dad at the wheel. What a

"dandy" he must been! And when another year went by, the Pierce would

end up in Yosemite Valley as a tour bus with many years yet to go.

Sadly, the lifetime warranty did the company in. Studebaker bought it

and allowed a slow demise, hastened by WW II, when its unique aluminum

engine blocks were melted for arms. Finding Dad’s car in a show today is

unlikely. My love of cars can’t be hereditary. It was acquired, like so

many wondrous things we are given by our parents.

I become “my

brother’s keeper”

There

was a strict rule in our house directed at me, age 5, and Ted, age 4.

Our scooter must never leave the upper driveway, for its course of some

60 feet to the street below was steep. Ted broke the rule. I called out,

"Bruder gone down the driveway." Who was punished? Not Ted, but Dick. I

had been informed that I was "my brother’s keeper." This rule is

embedded deep within me. I would repeatedly find that it would extend

well beyond such a narrow family designation in life ahead. There

was a strict rule in our house directed at me, age 5, and Ted, age 4.

Our scooter must never leave the upper driveway, for its course of some

60 feet to the street below was steep. Ted broke the rule. I called out,

"Bruder gone down the driveway." Who was punished? Not Ted, but Dick. I

had been informed that I was "my brother’s keeper." This rule is

embedded deep within me. I would repeatedly find that it would extend

well beyond such a narrow family designation in life ahead.

So

what was my trial at age five? The whooping cough, Pertussis, hit with a

vengeance. I remember long days in the dark in my upstairs room on

Highland with shades pulled as I hacked away and scared even my doctor.

The decision? We must move to a warmer, drier climate. The change in our

lifestyle made no difference as another Lyon characteristic surfaced.

The decision was prompt and action just as prompt. Mom and Dad sold the

house and we moved, lock, stock and barrel, to Sunol, some 50 miles

away. A family characteristic was becoming firmly embedded in this son.

Just assemble the facts, decide, and "Do It Now." I had been given the

blessing of being able to almost unconsciously daily assemble facts,

shunting aside emotions, and thus being prepared to make the required

decision without a moment’s hesitation. Was preparing as an engineer,

then a doctor, an early subconscious decision?

We move to the

country to help me live

Sunol was a child’s heaven. We slept in a

massive, screened outside porch. Each day we had miles of free walking

space through fruit trees and berry bushes bursting with goodies asking

to be picked. I can’t say it was that easy for Mom, because the cooking

was entirely in her hands. I guess I should have felt sorry for Dad and

his long commute each day on narrow winding roads through hamlets that

now are extended cities. But by then, even in my tender years, I knew

Dad was in seventh heaven behind the wheel of his Pierce. He always had

a tow line available to give someone out of gas or in a ditch a helping

hand. I am sure those driving hours were his time to think and plan, his

eyes never leaving the road and he alert to every nuance.

Apparently I recovered my strength after six months in Sunol. Dad found

a cottage in an abandoned nursery just one mile from the tiny hamlet of

Danville. It was closer to Oakland, and the highways were easier to

navigate. We promptly moved in. Of course, moving was duck soup. Lyon

was the mover. Mom was now in a cramped kitchen as she made the most of

natural food sources all around. Dad would usually drive the Pierce to

Saranap––yes that was its name––a station on the fringes of what would

soon be Lafayette. Then he would take the comfortable Sacramento Short

Line electric train through the long tunnel in the Berkeley Hills,

landing him close to his office in the just completed Lyon warehouse,

its clock tower a landmark. It seems like a toy as the Warren Freeway

brushes it to the north. I remember Dad, still in his thirties, telling

the powerful three in Oakland–––Capwell and Taft of department store

wealth, and Tribune newspaper mogul Joseph Knowland–––that the city

should dig another tunnel through the hills for automobiles. Their

reaction? "If we do that people will move to the country." Dad’s

rejoinder was, "They are going there anyway. If you don’t build the

tunnel, they won’t come into the city and buy in your stores."

Prophetic? You bet. And another Lyon characteristic was showing up. An

ability to recognize and assemble emotion-free facts that kept Dad

seeming to be well ahead of his time, most of the time. This is not

always a blessing I have since learned.

My dad

Dad’s story

really began when he graduated from Oakland High School. He was the rare

one who chose to go to college. The University of California was close

by. There he was known as the calculator guru. He was pictured that way

in the Yearbook of 1906. One day I asked Dad why he chose to go to

college in a time when the trades were flourishing. He said, "I wanted

to get an equal start with the best." Thus it was that in the moving and

storage industry, he and the Bekins brothers all were college educated,

and led the field throughout the country, especially when they became

founders of such long distance moving companies as Allied and Bekins.

Dad often mentioned that small local competitors, almost always

restricted to a van or two, did not have the advantage that education

provided. Dad would always be there with a helping hand. Thank goodness

they had the altruistic guidance of men like Dad, who cherished

competition but demanded it be the best it could be.

It was in

Danville that I first tasted school, a walk a mile to the east. I would

saunter back and forth each day with schoolmates recently immigrated

from Mexico. They had already picked up American English and

conversation was rich. We all carried lunch boxes and Mom would load

mine with goodies. My first grade teacher was Ruth Sorrick. I learned

later that I was the only blue-eyed blonde in her room of twenty or so.

And I was in hog heaven, for we all were encouraged to think and learn.

My classmates were alert and friendly. I think that had a tremendous

influence in making me so unconscious of ethnic backgrounds. Their dark

complexions and jet black hair were truly beautiful, and how we laughed

and played together.

One day Mom was in the center of Danville,

moving toward the bank to make a withdrawal. She was driving the Pierce

that day. She saw a man run out of the bank with a bag in his hand,

presumably stolen cash. The alarm was sounded and the sheriff

commandeered the powerful Pierce to make chase. Did the robber get away?

I think so. He might not have, had Dad been at the wheel.

That

was an idyllic world I know now, but I don’t have to look back and wish

I had understood that at the time. Why? Well, my parents constantly

demanded we appreciate the joys and blessings each day as just that––to

take nothing for granted. And it is the same for me today. If these are

God’s gifts, I say, "Thank you." If these are Man’s gifts, I say, "Thank

you for Man."

We return to the city

After

two years in the country it was time to return to the big city and its

challenges. Just before picking up stakes, my teacher, Miss Sorrick,

became Mrs. Lamborn. The blond blue-eyed "teacher’s pet" was the ring

bearer, and, for the first time I found myself playing hide and

seek—should I say flirting—with Jeanie, Ruth Lamborn’s niece and my

companion going down the aisle. I didn’t give in to her entreaties for a

kiss. Guess I blew it, and that would not be the last time. After

two years in the country it was time to return to the big city and its

challenges. Just before picking up stakes, my teacher, Miss Sorrick,

became Mrs. Lamborn. The blond blue-eyed "teacher’s pet" was the ring

bearer, and, for the first time I found myself playing hide and

seek—should I say flirting—with Jeanie, Ruth Lamborn’s niece and my

companion going down the aisle. I didn’t give in to her entreaties for a

kiss. Guess I blew it, and that would not be the last time.

By

this time Dad’s business was booming. We moved blocks up the social

ladder to Piedmont and 306 Sheridan, an English two-story house on a

narrow lot, surrounded by more imposing residences. It was just a mile

from Havens Grammar School and Piedmont High School, all on level

ground, easy to negotiate on bicycle, roller skates, or scooter. It’s

hard to believe now that a small bike was then a curiosity. Dad, always

resourceful, managed to find a much used one. Ted and I, as well as the

rest of the neighborhood, became cyclists by sitting on the bike and

pushing off from the curb. It was self-instruction at its best.

How did we live? Mom could now have

wonderful, supportive help with cooking and cleaning, as well as demand

a little discipline for the obstreperous three boys. Twelve quarts of

milk were delivered each day, and the despised cod liver oil was

replaced with a delicious expensive mix called Kepler’s Malt Extract.

Mom was presented with her new revolutionary electric mixer, the

KitchenAid. It was supposed to do everything. Applesauce was its number

one product, and I developed the trick of always mixing it in my milk,

something I still do today. And then there were the dishes. I have had a

lifetime familiarity with this because it was our chore after each meal

and continued to be my chore, among others, when I hashed my way in the

dining hall of Encina in my first Stanford year. There I set the tables

for 24, served, and then after setting up for the next meal, went

through the dishwashing routine. We hashers, for the most part athletes,

would sweep through the swinging doors, our trays with 24 glasses of

milk balanced above with one hand while the other hand opened the

swinging door. It must have been like a ballet, I think, looking back at

the wonders of being just a youth.

Why bring up this mundane

dishwashing activity? It was because I learned something else from my

Dad on how to get out of an odious job at home. Mom would say, "Harvey,

get in here and help the boys." Dad would roll up his sleeves, grab a

plate, somehow then letting it slip and crash to the floor. He had made

sure it was not one of Mom’s cherished Dresden cups or saucers. Mom,

then suckered, would exclaim, "Harvey, you’re always so clumsy. Get out

of here." A couple of winks by Dad at us boys, and he was back to his

newspaper. I haven’t had the opportunity to repeat that stunt. Could it

be that my coordination won’t allow it? I doubt that, particularly after

dropping and smashing a priceless Sevres cup when I broke the packing

rules as a "packer" on a moving job. I had been told more than once by

an experienced packer to always open a package over the barrel so if

something slipped it would have a soft landing. The owner of the cup was

a doll, thankfully, but the price of the cup made the lesson stick. I

was beginning to realize that mentors were always around if one just

listened.

How did Mom cope with the energies of three boys,

keeping them out of the trouble that seems the outlet for so many

without homes and caring parents? Well, one of the prices paid was our

furniture. We would wrestle in the front room, older, stronger Dick

usually putting Ted on his back with a hammerlock, until Bruce, five

years younger than me, insisted on getting his share of the action. It

wasn’t long before he would then hammerlock me from behind with Ted

down, thereby freeing Ted and winning the day. And then we would take

the long footrest from the front of the fireplace, place it in the

middle of the floor. Because there were three steps into the room, the

top of the steps was ideal for a running flying leap onto it. Needless

to say, springs rapidly flattened, and rather than get a new

replacement, Mom faced reality and kept the target in place until two of

us were off to college.

Bruce, with his living-room strength, had

the serenity we would all like to have. It came to the point that the

Havens School bully, an older sixth grader, challenged Bruce. He

immediately found himself vanquished as he was pinned to the macadam by

Bruce’s hammerlock. From that day on, Reg Kittrell was a pussy cat and

one of Bruce's best friends. I believe that was the only physical

confrontation any of us three boys ever encountered. So, unlike Bill

O’Reilly, was our compliance with reality a bad thing? Not at all. Early

on we three decided that even if our assailant got two black eyes and

lost the match, the price of being the winner with one black eye was a

price too high to pay.

Grammar school

What took place in grammar school that might have been a glimpse of what

was to follow? Third grade teacher Mrs. Haas, in her Mexican costumes,

planted the seeds leading to a lifetime desire to know the outside

world. My sixth grade teacher, Mrs. White, believed music should play a

major part in our lives ahead. She played and replayed such classics as

Meditation from Thais and Night on Bald Mountain, planting more seeds

that have blossomed and enriched my life. Perhaps most revealing of the

lifetime ahead was two years in Mrs. Lohse’s Latin class. Was this

searcher for ways to remember even then fascinated by the stems from

which our western languages have sprung?

Our first and

last larceny

One of my vivid memories of those years took

place when I was 13 and Ted 11–––the "Charleston Candy Bar" incident.

Dad always gave us our 25-cent allowance each week to be used for

whatever we wished, such as a Saturday trip to the Piedmont Theater

which required the streetcar ride to and from. Candy that would rot our

teeth was not on the accepted list.

Dad had a second method to

dispense the nickels and dimes we required to take the street car all

the way to Oakland for the essentials such as a visit to the dentist.

Ted and I knew very well that we were cheating, even stealing, when we

found ourselves taking more than was needed; we were breaking Dad’s

trust. How could this occur when both of us new clearly the difference

between right and wrong? Mr. Springman, pharmacist and proprietor of our

one pharmacy, also wondered about this. He phoned my Dad in his office

in the early morning saying, "Mr. Lyon, have you been allowing the boys

to buy chocolate bars on their way to school?" Thirty minutes later Dad

appeared in Principal Harry Jones’ office. He had a chore to perform and

would like to take his two boys home.

Into each classroom he

marched and, with finger beckoning, led us to the car and home and

upstairs where the looted bank was checked and the guilt assured. We

happily admitted culpability: Let’s pay up and get off the conscience

hook.

Dad did his needed part. Nothing was said. Down came two

pairs of pants, and Dad’s hand reddened, hurting as he administered our

first real spankings. Our reactions, not spoken but nevertheless

transmitted, were in essence, "Thanks Dad, we cheated. We have paid the

price." Thank you for what? No amount of discussion or reasoning was

necessary. We were stuck in our transgressions. Convicted, sentenced,

punished, and guilt removed, we could get back on stride. If that is

corporal punishment, so be it. It works, leaving no doubt as to right

and wrong. The debt is paid. Sure beats talking!

Looking back, I

have wondered why we didn’t just on our own "’fess up." I’m guessing

that we were also putting Dad to the test. Did he really mean what he

said about honesty and personal responsibility? Were we, having already

committed our crime, wondering how long it would take for Dad with his

adding machine mind to discover the robbery of his "till"? Dad trusted

his sons and would never have counted the nickels and dimes each week,

anticipating a robbery. It took Mr. Springman, outsider and real friend,

to accept the responsibility. How wonderful to have been allowed this

mistake, to then pay the bill once and for all and clean the slate, no

discussion required. Once was enough!

We adjust to high

school

Junior high school’s two years opened new vistas

as Mrs. Grover had us study the world, its peoples and geography. My

report on Uruguay lit an interest in the outer world that is just as

ardent today. These 7th and 8th grades were the first steps into high

school. Our classes changed radically. Most dramatic was the mingling of

students from Beach School in lower Piedmont from working blue-collar

families and our top of the world bunch, almost without exception from

from the moderately well-to-do to the very rich families consisting of

executives on both sides of the Bay. Could one be aware of any

difference? I for one could not, and our friendships knew no

limitations.

The girls all wore uniforms, as in most private

schools. I will always believe that the well-pressed quilted black

skirts, and loose white middies made an immense difference, stimulating

the boys to dress with the same neatness and without pretense. This is a

practice that today should be a starting point for inner-city schools,

the government paying for these uniforms that level the playing field

and stimulate classroom performance through personal pride

Yes,

we had clubs, but these were for the most part unpretentious. I was a

Kimmer, mostly drawn from upper Piedmont. Many of my best friends were

Rigmas, from the other side of the tracks, so to speak. I don’t remember

much competition, save as to the type of soft drink each would serve at

parties. As athletes, there was no club loyalty, and if initiations were

the same, Ted and I would have hated both. The inane use of the paddle

to soften up us new members was primitive. By the time we two had

finished our high school years, we had made sure the use of paddles was

on the skids. I remember so well that I received some fifty blows––yes,

I counted them––and finally turned to my tormentors saying, "You guys

might as well quit. My butt is numb and you’re wasting both of our

times." On the other hand, Ted’s fanny was swollen and red. No wonder we

condemned the whole thing.

It was clear from the very start that

Mom and Dad approved of our determination to treat our companions as we

would like to be treated, and that is still the rule. I now think that

"empathy" was heavily in our genes right from the start, aided and

abetted by my parents, who made sure their sons understood that the most

offhand remark must be recognized for the meaning it carried to others.

Forming our views of the world

Looking back,

I realize that skin color was never an issue. Takeo Hamamoto was our

number one tennis player and greatly loved. He had come to America,

surely from a leading family in Japan, and was making his way as a

houseboy. To us this was admirable. How I wish I had followed him to the

internment camp as the war with Japan began. I never understood why

President Roosevelt was not better advised. He should have allowed these

wonderful people to return to their homes and as Americans, to aid the

war effort. I understood the need to initially get them off the streets

and protected from militant kooks, but we missed the boat. As the years

went by and I worked with Japanese-American nurses, I became convinced

that no ethnic group more quickly adapts to our ways. This was

buttressed by our later prewar experiences as we traveled the world,

Japan our starting point. My point is that our home training left no

doubt that our judgments of others, and ourselves, would have only one

dimension. This was quite simply "character." And it is the same for me

today.

Piedmont High School daily took me closer to the time I

would have to leave the protection of home and community as the step to

college must be made. Somehow, I was acutely conscious of the blessings

I was enjoying, not really looking forward to college, where the big

decisions would be made. Some of my friends were anxious to get away and

get started toward clearly defined careers. Easily, the embryo doctors

led the list. Engineers, writers, and artists seemed to follow. I, on

the other hand, chose to wait and let the chips of direction fall. I was

in no hurry to confront responsibility. I milked each day for all of its

worth.

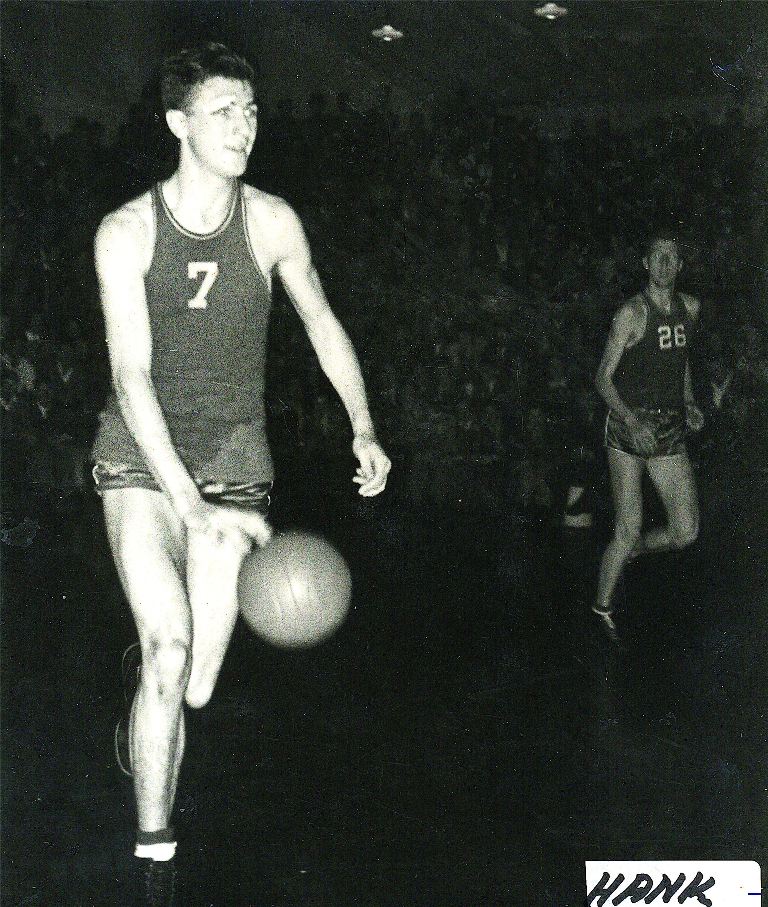

A non-combative world for me as mentors appear

In

personal histories, often a great deal of time is given to demonstrating

one’s ability to court confrontation while not compromising principles.

This was not an option for me. I don’t remember a single instance of

such combat, nor do I remember compromising on principles. We brothers

seemed to have sensed from the start that we did not require the

approbation of others to follow our inclinations. Combat? Yes, on the

basketball court or rugby field, as part of the team. Yet, I saw this as

just fun and admired so often the abilities of the athlete who was my

opponent. I remember being benched in a basketball game with USC when

the "almost All American" center out maneuvered me for a lay-up basket.

I hit him on the fanny with my hand, saying "Nice going, Gale." Coach

Dean’s advice was "Get mad." I didn’t know how. I stayed benched for the

rest of the game. In

personal histories, often a great deal of time is given to demonstrating

one’s ability to court confrontation while not compromising principles.

This was not an option for me. I don’t remember a single instance of

such combat, nor do I remember compromising on principles. We brothers

seemed to have sensed from the start that we did not require the

approbation of others to follow our inclinations. Combat? Yes, on the

basketball court or rugby field, as part of the team. Yet, I saw this as

just fun and admired so often the abilities of the athlete who was my

opponent. I remember being benched in a basketball game with USC when

the "almost All American" center out maneuvered me for a lay-up basket.

I hit him on the fanny with my hand, saying "Nice going, Gale." Coach

Dean’s advice was "Get mad." I didn’t know how. I stayed benched for the

rest of the game.

We Lyon brothers had parents who always took

part to the degree that Dad and Mom were each presidents of the

respective Fathers and Mothers Clubs for as long as five years. Didn’t

anyone else want these jobs? Perhaps, but I never heard a criticism.

This pattern of accomplishment extended to Oakland’s Children's

Hospital, as well as to the local business and charity organizations,

Mom’s almost-Presidency of the National DAR, and Dad’s Presidency of the

National Warehousemans’ Association. Were we boys impressed? I don’t

believe so, for we saw our parents just as feeling obligated to be

effective in anything thrust upon them. Sounds too good to be true, I

guess, but this was an ingredient manifest in most communities in the

America of that day. And when our parents funded and thus created the

Bruce Lyon Children's Hospital Research Laboratory as a memorial, it was

just the natural thing to do, no matter the family largess that was

required. The Bruce Lyon Grove of redwoods at the Oregon-California line

carries the same message.

Humor was part

of our daily fare. At the dinner table Dad would tell us his latest

joke, the punch line of which he had already posted in his little black

book. He accumulated one book for each year, kept them in his dresser,

and then at the end of a long lifetime must have discarded them. They

were lost to his boys. No matter; his sons knew almost all by heart, so

often did he tell them to illustrate a point. I have that habit today

and call them shaggy dog stories, not sure that today’s listeners think

them at all funny, but Dad was famous in the Bay Area for his fund of

jokes. Prominent men such as UC Berkeley President Robert Sproul and

Oakland District Attorney Earl Warren would drop in for a story

befitting a specific occasion, the latter even as Chief Justice of the

United States Supreme Court. His best jokes seemed to be pointed at

one’s self, demonstrating a kind of humility, I think. I like to believe

that this is really the case, because it seems to be familial. Taking

one’s self too seriously is a tough load to bear.

Dad’s

booby prize

Sometime in the 1920s, when Dad was president

of the California Warehousemans’ Association, he went to Florida for a

convention, played golf, and came back with the booby prize, a tiny

alligator. That little organism somehow made the five-day train trip

home. He was "fenced" in the back yard and grew large enough to threaten

our chow dog, Ching, so Dad made a deal with the owner of the plush

Broadway Restaurant in Oakland with its multiple fountains. And for

several weeks or months he was an attraction there until he started

chasing the waitresses. He ended up as the first reptile in the new

Oakland Zoo in Montclair, a happy beginning for hopefully a long life

from prize to perpetuity, since alligators have long life spans.

My first mentors, after Mom and Dad

How many of

my teachers became mentors for me? What is a mentor? There are teachers

from whom we learn, but teachers become mentors when they discern

something in one that lies perhaps undiscovered that must be encouraged

to blossom.

First there was Brick Johnson, a Scot if there ever

was one, so strong, demanding, and principled. His bagpipe band was the

real thing. I practiced on my chanter by the hour, but could never be

available to play the pipes because I was on the playing field, being

encouraged on by them. Brick was also my Sunday School teacher. He

characterized Christ in a way that has impacted me to this day. He said,

"Christ was a powerful man, not as he appears so often in art. Could any

of you in the best of condition carry that cross to the top of the

hill?"

Brick was co-coach with Sam Moyer and believed that men

are made on the field of competition–––football in this case. There was

another believer, Harry Jones, our principal. Each year he would tell

the story to the 1,200 of us of his exploits as a teacher in a tiny

Midwestern school, where student ages ranged from 12 to 22, all in one

room. He had a physical confrontation or two and quickly decided there

must be a better way. Pop Warner, now legendary, had written a small

book entitled, The Forward Pass. Book in hand, Mr. Jones found two

receivers, and a boy-man who could throw the ball. For three years this

tiny school won the state championship, finally taking on the collegiate

normal schools and defeating them by scores into the nineties.

What was the secret of such success? It was a combination of surprise

and habit. It took years for the surprise to end, as habit gave way to a

better way to play. What was the lesson to me? Although we pride

ourselves in adapting to something new each day, in fact change is more

likely to be slow. It would be years before I would test this principle.

It was Principal Jones’ contention that it was on the football field

where one becomes a man. I was in the 10th grade, beginning to sprout to

an eventual 6’2” with the 126-pound weight of a bean pole, really little

different from a newborn colt. The appeal to manhood was so effective

that ninety boys showed up, and ninety uniforms were filled. I succumbed

and was given the ninetieth uniform, a ratty affair, putting me on the

ninth and last string. I was bottom of the line, but that seemed to be

not a factor, for we all had to learn how to tackle and block. It would

have been wiser to send me on the run with the order to catch. But, no,

first I had to learn to tackle. Guess who was my first runner? It was

the Coach’s son, first-string fullback Dick Moyer, 5’6” and a rolling

ball of sheer, hard muscle.

I promptly decided I really wasn’t

ready yet to be a man. My young, growing, loosely-protected bones would

shatter just to have Dick Moyer look at me. I ran to the sports house

and into Coach Brick’s office, shedding my suit, claiming cowardice. To

my amazement, he laughed and said, "Take off that suit and go up to the

gym and grab a basketball." That did it. I wasn’t a coward after all,

and he had better plans for me as he directed me to the sport that would

make me All Conference center and then a teammate of the man who would

change the game, Angelo "Hank" Luisetti.

Beyond Mom and Dad,

mentors like Brick were just beginning to appear. I had quite wonderful

teachers, not in the roles of serious mentors. There was Mrs. Beebe, who

tried without success to make me write using the Palmer full-arm method.

I would get a B at best. I could not satisfy Mom’s desire to see me with

all A’s to make her sure I was as smart as buddy Albert Rowe. He, like

his famous dad, a pioneer in Allergy, was on his way to being a doctor.

I made a deal with Mrs. Beebe: If she would promise not to watch me as I

wrote with hand motion alone and grade me instead on the written results

that deserved an A, I could please Mom. Once straight A’s reached home,

Mom was satisfied. I said, "Mom, that’s it." I could return to

imperfection, and did.

Dr. Niemann, chemistry teacher, although

full of imaginative presentations, could not pierce my inability to

memorize easily. The need to use trial and error in constructing an

equation left me cold. Even then trial and error was the last thing I

wished to use in speeding my understanding of truths that would guide my

life. Mr. Banker, historian, was also a fine source of historical facts,

but didn’t quite have the enthusiasm to give facts life.

Mr.Weingarten was the winner, as far as I was concerned. Algebra was my

joy. It didn’t have to be memorized. Understanding it just required

common sense, my long suit conditioned by a dad who exuded it. Geometry

was a close second as it stimulated the small bit of the artist in me,

suspending Algebra in the third dimension of space. But, then came

Trigonometry. I didn’t know then why it was so difficult.

Years

of experience later revealed that I had a serious deficiency, by

teaching standards. I couldn’t memorize what I couldn’t quickly

understand. A formula demanding a complex of plusses and minuses all

square-rooted had to be taken at face value. I simply couldn’t do it,

and this deficiency would later play a major role in directing me to my

life’s work. The Process Mind was beginning to manifest itself.

And then there was Assistant Principal Bolenbaugh, who installed me as

head of the Student Council, charged with discipline and moral issues.

He knew even then that I would be unlikely to win the popular vote and

hold an elective office. That had already transpired when Chaffee Hall,

un-athlete of the year, dearest friend and the Daily editor, whipped me

in the election for the most coveted job, Commissioner of Entertainment.

The irony and final nail in my political coffin was the fact that Dad

was providing most of the entertainers. I would seem be the logical

choice. Dad performed the same service for Chaffee.

Mr.

Seagrist, our Physics teacher, made the course fun for me as it was a

challenge to understand physical laws that guided so much of our lives.

The quick memorizers did their thing and scored well. I, on the other

hand, had the privilege of working to understand. I guess my A was well

deserved. I was beginning to accept that I had to understand principles

and theorems before I could commit them to a memory that wasn’t

overnight but would likely last a lifetime. In retrospect this has

turned out to be the case.

Mr. Hampton, always a little

absentminded, never learned of the risks I blithely took when I chose as

my term project, chromium plating. This required a combination of

chemicals that produced toxic cyanide gas as an end-product. How to get

rid of this? In our basement I boiled my mixture under a large funnel

and hose directed outside to exhaust the gasses. I survived the process

and received an A. You can be sure I kept the matter to myself, and

accepted that at times a little bit of luck is a very good thing. I

shudder now as I look back at my innocence.

Before and

after "The Crash"

I

well remember one day on Sheridan in 1928 that Dad had caught me leaving

the the front bathroom. He stepped in closed the door, and said, "Dick,

I have to tell someone. Your Dad is a millionaire." Guess I must have

said, "Nice going." I recall that I was not impressed, for our living

habits were wholesome and not changing, Soon after, however, we moved

into the Big House at 25 Crocker, with a porte-cochere and all the

fixings. I

well remember one day on Sheridan in 1928 that Dad had caught me leaving

the the front bathroom. He stepped in closed the door, and said, "Dick,

I have to tell someone. Your Dad is a millionaire." Guess I must have

said, "Nice going." I recall that I was not impressed, for our living

habits were wholesome and not changing, Soon after, however, we moved

into the Big House at 25 Crocker, with a porte-cochere and all the

fixings.

As I started Junior High School, the Crash of ‘29 began

to take it's toll. We were then living in what I called "The Big House"

on the most prominent corner in Piedmont, Crocker and Wildwood. Three

years earlier as Dad prospered, he bought the Abbott house and spent

$25,000 renovating it. It was a spacious colonial mansion, its interior

almost entirely the dark woods of mahogany brought from the Far East. It

was impressive but oppressive. Off-white paint covering this magnificent

wood made it light and airy. Each of us three boys had our own bedroom

and bath for which we chose their colors. Mine was an impressive green

with black trim. In a way, we reveled in our new luxury, but the price

included much garden work for us and Mom. The garden work paid 25 cents

an hour, pure wealth. Dad, with his usual foresight to cover the

improbables of the future, rented the 306 Sheridan house as a backup. It

was just two blocks away.

Life on Crocker in our mansion called

for more help. In Piedmont grandee style, my parents hired our first

Chinese cook, Lee Wong. Loyal, pigtailed servants were fixtures in the

homes of most of the the truly wealthy families. He never took a day

off, living in his small kitchen-side room. Can one imagine this change

in lifestyle for three boys brought up in a single desk-filled room with

one closet, three beds on a porch, and within 200 feet of trolleys that

constantly banged as they switched night and day? In truth, if there was

a quiet holiday, the silence would awaken us with a "What’s that?" from

one of us. Our second new household member was a "house boy" from the

Philippines. It was serene for a few weeks, but when Lee went after the

house boy with a kitchen knife, we realized that Lee was quite enough,

and the chores of making beds and Saturday cleaning were back in place

for the three of us.

I don’t think anyone around us took much

notice of the new inhabitants until Dad saw beautiful white cutout deer

lighting up a Christmas display on Piedmont’s most imposing lawn just a

few blocks away, that of Wallace Alexander. Dad got the idea

immediately. He brought the two life-sized paper maché lions from his

warehouse, and we placed them appropriately on the lawn beside a fir

tree. A scattering of make-believe snow completed the tableau. Cars

going by almost crashed with drivers astonished at Africa in the cold.

That did it! Mom ordered Dad to cease and desist, especially when

someone accused her of advertising Let Lyon Guard Your Goods.

Almost over night, Dad descended from millionaire status to a debtor of

a million dollars. How did Dad survive such times? He went to each bank

and, in so many words, said, "If I am forced into bankruptcy, you will

get nothing. If I agree to pay you 50 cents on the dollar in

installments, you will gain the most and perhaps I will survive." They

were convinced. Over the next nine years Dad, bag in hand, collected

moneys from such as the parking lot he had owned next to the Paramount

Theater. Dad had invested heavily in Oakland prime property. The banks

had been too lenient in allowing loans that within a matter of weeks

were more than the properties were worth as their values plummeted.

“Home” returns to 306

As

the world came tumbling down, we moved again back to 306 Sheridan, lock

stock and barrel. It seems odd, but I don’t remember much about the

move. It just seemed that we were really home again. The small family

room again was graced by the Philco radio, but the furniture breathed a

sigh of relief as our energies, now more channeled, did not include

wrestling. It was back to the single three-boy bedroom, now a little

smaller as we all became bigger. But the fit was easy, and life for us

just took up where it had left off. Mom no longer would be weary from

the incessant demands of a large garden. We boys had a smaller lawn to

weed and mow. Our weekly stipends of 25 cents were not cut, but the

chances for added cents became limited. At the same time, Dad was each

day making his deposit in the bank to pick away at each loan. That took

nine years of daily humbling. The memory is fresh today of Dad stopping

me in the rough at the brow of Orinda Country Club’s fourth hole. As it

was that day in the bathroom, Dad said, "Dick I must tell you something.

Your Dad doesn’t owe a single cent to anyone." If his eyes didn’t tear

at that moment, I would be surprised, for my eyes tear today just with

the thought. As

the world came tumbling down, we moved again back to 306 Sheridan, lock

stock and barrel. It seems odd, but I don’t remember much about the

move. It just seemed that we were really home again. The small family

room again was graced by the Philco radio, but the furniture breathed a

sigh of relief as our energies, now more channeled, did not include

wrestling. It was back to the single three-boy bedroom, now a little

smaller as we all became bigger. But the fit was easy, and life for us

just took up where it had left off. Mom no longer would be weary from

the incessant demands of a large garden. We boys had a smaller lawn to

weed and mow. Our weekly stipends of 25 cents were not cut, but the

chances for added cents became limited. At the same time, Dad was each

day making his deposit in the bank to pick away at each loan. That took

nine years of daily humbling. The memory is fresh today of Dad stopping

me in the rough at the brow of Orinda Country Club’s fourth hole. As it

was that day in the bathroom, Dad said, "Dick I must tell you something.

Your Dad doesn’t owe a single cent to anyone." If his eyes didn’t tear

at that moment, I would be surprised, for my eyes tear today just with

the thought.

Dad saved Lyon Storage and Moving Co. with the help

of $17,000 from grandmother Richards, then, occupying our guest room. It

was a mighty tight squeeze. Still nursing his pride, Dad could now

afford only an Oldsmobile. For a year he parked around the block in

hiding. He believed he must maintain the mantle of success. I suspect it

was a help. Several Piedmont friends took their lives for insurance

support for families. Mr. Hamby lost his magnificent grocery store as

the wealthy ran up immense bills, never repaid until too late.

True Grit, as we look back

Dad demonstrated the

truth of his lessons to his sons as he took his beatings without a

moment of self pity. I never heard a complaint as he recognized his poor

judgment, although events that took place had been correctly anticipated

by only a few. But an event just before The Crash throws light on the

values he passed on to his sons, these values having a price.

In

1927, two years before The Crash, Dad decided to expand Lyon Storage and

Moving Co. by adding a second unit in San Francisco. Things must have

been going well, for this was the prosperous run-up to 1929. He acquired

perhaps the choicest property in San Francisco. It was directly across

from the City Hall in the Civic Center. Today it is hard to believe that

finding and acquiring such a nugget was possible. The warehouse was to

be the finest in America and a standard for fire proofing advances that

assured storage safety. The foundation was complete and the first floor

underway, with $10,000 worth of steel already delivered. Then the axe

fell. Horace Clifton, chairman of the San Francisco Board knew that a

fine orchestra would remain a dream without a true Opera House. It was

now put up or shut up, all set in motion by Dad’s foresight. The city

fathers gave in. The property was condemned for public use but Dad was

offered any other available property he would choose.

Dad, in the

meantime, had second thoughts about this new venture. Crossing the Bay

meant lost time on the ferry each way daily–––no bridge then–––and this

time had become precious for it invaded time at home with his family. I

believe he quietly sighed with relief, reclaiming the funds and happy to

be a big guy in then a little pond.

The story now takes an

unexpected twist, for this was the heyday of property and stock market

values. He took the funds and bought TransAmerica stock, believing it

golden at a value of over $200 a share. Over the next two years, it

steadily worked its way down. Only when it reached $100 did he ask his

sons’ opinions, our ages to 7 to 12. Our decision was unanimous: "Sell."

Dad didn't take our advice, and then watched TransAmerica plunge to

zero. That was when the full impact of The Crash hit home. No tears from

Dad. He would just "gut it out." Lessons for his boys? You have only

yourself to blame when things go badly. Quietly, bite your lip and get

on with making the very best of it.

Life-preserver golf

It would seem that a sport would just

provide delightful memories throughout our growing years, but in our

case, golf was something quite different. It came close to being a way

of life, teaching us lessons that would help us through difficult times

yet ahead.

Dad, in his prime, had been a founder of Orinda

Country Club, a gem in the hills just one half hour away from home. We

three boys and Dad started playing as we reached age ten. This was a

family affair from the start. The Sunday picnic on our lot, intended for

a home someday, was followed by the Lyon eighteen-hole foursome, Mom

biding her time reading and knitting. Dad, even with all of his worries,

kept our game a ritual.

Ted and I became proficient golfers,

making up the second pair on the high school team. We never lost a

match. It was years later that I recognized why. Younger brother Ted,

with his consistent, upright, finely-honed swing went right down the

middle. I rarely was able to best him. I, on the other hand, was a bit

wild, but long. In our matches, at about the fifteenth hole, we would

begin to pull away. Why? Because our opponents would start to spray

their shots as they tried to get the longest drives. I would often do

the same, while Ted went down the middle and we won the closing holes.

Our golfing buddies couldn’t understand why we wouldn’t be intent on

competing with them more often and thereby improve our games. We never

offered an explanation. We just played as a family together.

The

finale to all this is that when Dad’s world came crashing down, his sons

were his shock-absorbers–––always there and ready to go. The country

club should have been one of the casualties, and our golf therapy for

Dad would have been denied. Was someone looking after us, we wondered,

for Dad’s founder’s lifetime membership demanded no dues, and our locker

was $1 a month? Golf balls? No problem. After the Sunday game, we

trekked back to the thickets lining the course. Ted somehow found just

new balls. I found mostly “rocks,” but we shared everything, of course.

To this day, golfing buddies can’t understand my attitude towards

the game. It is the same in other "one on one" sports such as tennis and

swimming. There must be something wrong with me if I am to judge from

the many books on individuals where winning is "the name of the game."

It is true I didn’t like to lose so often to brother Ted, but at the

same time I gained no joy out of being the winner. To this day, this

intent is the same. I prefer to come out even, both of us having played

a fine game. Many times as I faced a one-foot putt to win, something

inside would trip my hand to make me miss. Had the putt been necessary

for me to secure a tie, I would calm myself and sink it, usually. We

would be even. My joy has always been in the game that I played within

myself.

My future: doors kept open ahead

I was 14, and beginning to think about what I would like to do

with my life. Our year studying the outer world in geography class in

junior high school rang the bell. The outside world, so far away, seemed

almost inaccessible, but it beckoned. I would join the Foreign Service

and see that world. What could give me a helping hand? Practical from

the start, I imagined diplomats in white tropical suits, long pants and

all, cavorting on the tennis courts. Golf then was still in its

diplomatic infancy. A first step then would be to become competent in

tennis, and I could be a desired partner on the courts when ambassadors

needed talented partners to win their contests.

This was later

borne out when Dr. Bill Smart, dear friend and champion golfer, as a

mere Lieutenant would in innocence walk through the officers mess on his

aircraft carrier in golf attire. His golf cleats clanged on the deck

before he stepped into the Admiral’s gig for a game that day. And we

were at war!

Berkeley Tennis Club was a major center of great

tennis. Locals Helen Wills and Dorothy Jacobs were world champions. I

took the street cars, changing as necessary, and met with the tennis

pro, Mr. George Hudson. He agreed to give me 10 lessons at $4 a lesson.

I had $40 from weekend gardening jobs. The ten weeks went rapidly by. I

was given a firm basis for a classic free-swinging game, although there

was no time in between to practice. Nevertheless, my game was good

enough to make the third pair of Piedmont’s team, while golf and

basketball teams were not neglected.

So, what is my point in

telling this story? It is to strive to be taught only by the "best"

right from the start. If it requires long rides on the trolley cars, so

what. Just make it work. So Do It Now.

Away from home at

college and value of the name Lyon

Graduation

meant the first major change in a life pattern so ordered thus far. In

1934 it was time to break the comforting and ever encouraging bonds of

home. What did I wish to be? I hadn’t the slightest idea, for my talents

seemed so ordinary in the face of my buddies with gifts in music, art,

and writing. We were confirmed "Golden Bears," and UC Berkeley was to be

the next step in preparing for my life’s work. At this time I was

high-point man, the center, on a winning basketball team. I had earned

"All Conference" status. So, along with 10 others originating in the

western states, I was offered a scholarship at Stanford. Dad’s doubts

about financing my college education without my living at home were

relieved. Graduation

meant the first major change in a life pattern so ordered thus far. In

1934 it was time to break the comforting and ever encouraging bonds of

home. What did I wish to be? I hadn’t the slightest idea, for my talents

seemed so ordinary in the face of my buddies with gifts in music, art,

and writing. We were confirmed "Golden Bears," and UC Berkeley was to be

the next step in preparing for my life’s work. At this time I was

high-point man, the center, on a winning basketball team. I had earned

"All Conference" status. So, along with 10 others originating in the

western states, I was offered a scholarship at Stanford. Dad’s doubts

about financing my college education without my living at home were

relieved.

Then came the June surprise: Coach John Bunn called to

say that the Board of Athletic Control denied my scholarship because the

name Lyon of Lyon Storage and Moving with its slogan, Let Lyon Guard

Your Goods was too well known. Stanford could not be seen to be

subsidizing wealth. This was in the early days of Dad’s recovery.

Technically, he was still broke. I faced Dad in the back porch that

evening.

"Dad," I said, "How much is the name Lyon worth?"

Dad retorted, "What do you mean by our name having worth? Give me a

figure?"

"Dad, is it worth $345 a year?"

"What’s that?"

"That is the tuition at Stanford for a year. You give me the

scholarship and I’ll work my way through."

Dad said, "OK. It’s a

deal."

Thus the Lyon Scholarship was created. He paid up and I

worked, hashing at Encina Hall as a freshman and then hashing again at

sororities. I worked for a small government grant doing book work and as

a private contractor washing "well-to-do" boys’ cars. I did odd jobs in

the summer, and in my last year all needs were met as house manager of

my fraternity.

CHAPTER 2

I GO TO COLLEGE

Stanford beginning

My

first quarter of the academic year was a difficult one. In order to get

by financially, I lived for three months in a small room with bath at

the back of Coach Bunn’s home. I never had a meal there, let alone saw

the dining room. Its distance from the campus meant arising early in

order to hash at Encina Hall, followed by a busy day of classes and

basketball practices. Not having a room at Encina Hall kept me from

getting into the swing beyond making new friends on the court. Weekends

at home were a refuge. My

first quarter of the academic year was a difficult one. In order to get

by financially, I lived for three months in a small room with bath at

the back of Coach Bunn’s home. I never had a meal there, let alone saw

the dining room. Its distance from the campus meant arising early in

order to hash at Encina Hall, followed by a busy day of classes and

basketball practices. Not having a room at Encina Hall kept me from

getting into the swing beyond making new friends on the court. Weekends

at home were a refuge.

Something had to change! Dad agreed to

help with costs as I moved into Encina Hall in January and could then

take part in campus life, my hashing duties now next door. I would find

it a joy in the sophomore year to live in the fraternity house, my home

for the next three years, as well as the dining table later during the

months on campus in medical school.

I play basketball

with the coming star, Angelo Hank Luisetti

Hank

Luisetti proved to be all that was expected and a joy to be with on the

team. From the start the competition was intense. As the days wore on,

our diminutive, feisty, freshman coach tried different combinations. I

usually ended up with Hank as the other forward or as center. Hank

Luisetti proved to be all that was expected and a joy to be with on the

team. From the start the competition was intense. As the days wore on,

our diminutive, feisty, freshman coach tried different combinations. I

usually ended up with Hank as the other forward or as center.

We

started our season in Auburn, heralded there as the "great team" we were

on our way to becoming, winning all but one of our games. That game I

most remember for it was our opening encounter with the Cal frosh. We

gained our first dose of what a "hot" team could do. Cal players such as

Chet Carlisle and Ed Dougery couldn’t miss no matter from where they

threw the ball. We tried three kinds of defense yet lost miserably. The

irony was that each year for the next three, the same "hot night"

occurred at Cal, so that almost our only losses were these and they were

clearly won by Cal, to their absolute joy. I remember so well Dougery

just standing there and tossing while laughing in my face. Strangely, in

all my Stanford years, I don’t remember a hot Stanford team night. If

Hank couldn’t hit, he would shoot anyway, and then on a first or second

followup on the shot, ram it in, something no longer possible with the

giants under the basket.

Hank was the

consummate basketball player, the equal of the modern stars such as

Michael Jordan who seem so superior. This is largely because of their

freedom to take three steps instead of two, to palm the ball in the

dribble, and to strike the basket rim as they dunk. I have the clipping

telling of the foul I incurred as my wrist touched the net on a lay-up.

I guess "white guys could jump." The dunk changed that, not to the

advantage of the game. I saw Hank make the first dribble behind his back

as he left the All American USC captain, Hal Dornsife, just standing

there, then throwing up his hands as though asking the crowd what they

would do. Hank’s defensive moves were unmatched even today.

Engineering to Hygiene to Engineering

Now the

awakening! My first semester was a disaster, for Descriptive Geometry

turned out to be Trigonometry all over again, yet magnified. My

professor named Butter made me feel just "too dumb to get it." I had no

intention of continuing if I couldn't "get it." So I dropped my major

and switched to Hygiene, at least to get my breath and regroup.

At that low point I pinned Mom with the question, "What was my IQ on the

Terman Test?" Mom hesitated, but I was not to be denied. She said it was

136. What a relief! I wasn't anywhere near a genius at 140 or above, but

was in a range where I hoped sheer determination, persistence, and hard

work could make anything possible. I let things go at that until–a

miracle? Yes, I think so as I look back.

Dr. Harold Bacon (thank

goodness not Butter again), Professor of Mathematics, was the "timer" at

our freshman games. He had heard that I had dropped out of Engineering.

As a freshman, I was playing forward with Hank Luisetti, trying to

emulate his one-hand push shot that changed the game. Dr. Bacon asked me

to go back into Engineering and repeat the first year of math with him,

and somehow we would make it go. He backed up his promise, each week

devoting several hours to coaching what I know now was my Process Mind

to make sense of Descriptive Geometry, and Differential and Integral

Calculus. A key boost to my confidence came when I earned one of the

three A’s in Integral Calculus. The other two A students were in another

realm, I believed. They had done the assignments in an hour and were

playing pool when I asked for help.

Yes, HWDP–––Hard Work,

Determination, and Persistence–––could make the difference. I never

would doubt that again.

A big step that took years to

understand

Now a jump forward to cement the contention I

have just made. My Hydraulics course, considered the most demanding both

in substance and in performance, was taught by Dr. Hedburg, a

no-nonsense guy. As I walked into the final exam room, I was blown away

by the activity. Students were burning up their slide-rules, making

calculations seem easy. I panicked.

I asked Dr. Hedburg, "May I

go to the House and do my exam, please. My head is spinning."

"Of

course." We both knew that no book could help.

Four hours later I

turned in my Blue Book. I commented that, "I think I have flunked the

course."

His rejoinder, "We’ll see." Two days later the blue book

arrived with an "A" on it.

I went to the engineering corner and

said to Dr. Hedburg "I think you should look at this. Your corrector

must have made a mistake."

Dr. Hedburg said, "There is no

mistake. In fact, you got the highest grade in the course."

"Please, Sir, how could that be when I really didn’t know what I was

doing?"

"Well, you derived every equation."

This statement

meant nothing to me at the time. Of course I was thankful for this

judgment. There was perhaps something worthwhile yet ahead. It took over

sixty years for me to understand the prediction of that day. It was my

Process Mind at work. It would pursue its course through all my

professional life, and even after. It would only be in the “after” of

retirement and time for contemplation that I would strive to understand

this Process in order that others like me with HWDP could early on

recognize their possibilities and then realize their full potentials.

The "Straight A’s" would not be able to keep up.

CHAPTER

3

1936 AROUND THE WORLD

This

next section of Dr. Lyon's book deals with his Rotary experience in

1936. This

next section of Dr. Lyon's book deals with his Rotary experience in

1936.

Grandmother Richards takes over

In the spring of my

freshman year, as our Luisetti team took all the honors, my beloved

Grandmother Richards passed quietly away as her kidneys failed, the end

point of scarlet fever acquired in the waters of Sutro Baths near the

Golden Gate. She had been living with us for sometime. I had many talks

with her, for I was becoming a history buff. Her tales about the Old

South and the Civil War never tired me. Gram knew I had a dream, quite

impossible to achieve, of riding a bicycle through Europe, so far away

from home and family. Air travel was then restricted to pioneering Pan

American flying boats to Hawaii and South America. The telegraph was the

only reliable means of direct communication and not available

everywhere. So, dream on Dick, no charge, as you still have the Foreign

Service in your prospects.

Gram’s Will made this dream come true.

Ted and I were each to receive $800 that could only be spent riding

bicycles in Europe. There was no backing off from this commitment, and

there was a time frame dictating "now." The year was 1936, and the

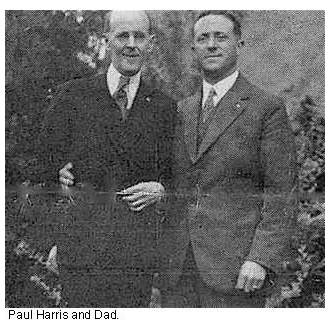

Olympics would be in Berlin.Lyon

Dad and Mom, faced with an

obligation that must be met, frightened of course, started to plan. Both

of them, always making something odious into something good, decided

that the $1,600 could be stretched to take us around the world. Dad

would make us into Rotary Ambassadors of Goodwill by enlisting the help

of Paul Harris, Founder of Rotary, that was by then in 57 countries,

many on our route. His letter assured our parents that their sons would

have helping hands when in need, and further, that two American young

men, whose teeth were cut on a Rotary Wheel, could strengthen the ties

that bind this organization. Dad sent the letter to the clubs in each

major city on our route.

We leave our home for eight

months to see the world

The hours riding in the bus to Seattle

were the only ones on the trip that were troubled by any apprehension.

The enormity of our undertaking was becoming obvious. By the time we

boarded the NYK Hiya Maru, our confidence had reestablished itself and

our days would be dedicated to planning ahead.

The trip in winter

in the subarctic seas was a rough one, our sturdy ship and equally

sturdy captain plunging along. The ten passengers made common sense of

using first class comforts, returning to second class for meals, there

chasing plates as they careened, some to the deck. No one was seasick.

There was really no time to sit in a deck chair with nothing to do

except respond to the environment.

Japan

Our Rotary

involvement began the day we landed in Yokohama. We were met and were