|

American Supra: Book Two

First Days and An

International Artist’s

Workshop in Kutaisi,

Georgia

The dynamic principle of

fantasy is play, which belongs also to the child, and as

such it appears to be inconsistent with the principle of

serious work. But without this playing with fantasy, no

creative work has ever yet come to birth. The debt we own to

the play of the imagination is incalculable.

Carl Gustav Jung,

1875-1961

Democracy- the essential

thing as distinguished from this or that democratic

government- was primarily an attitude of mind, a spiritual

testament, and not an economic structure or a political

machine. The testament involved certain basic beliefs- that

the personality was sacrosanct, which was the meaning of

liberty, that policy should be settled by free discussion;

that normally a minority should be ready to yield to a

majority, which in turn should respect a minority’s sacred

things.

John Buchan Lord

Tweedsmuir, 1875-1940

To leave is to die a

little;

To die to what we love.

We leave behind a bit of

ourselves

Wherever we have been.

Edmond Haraucourt,

1856-1941, from Choix de Poesics (1891)

Early Morning, Tbilisi, Georgia, 3:05 a.m.

Flying into Tbilisi is a strange experience since the

Turkish airline flight plan above our heads reads “1:53” for

landing and we know from the American Embassy of Georgia

that we are to arrive at 3:05 a.m. Our ticket reads 3:05

a.m. The thought flashes across our minds, “Did we get on

the wrong flight?” We are not really sure so we ask,

“Tbilisi?”, pointing to the ground, and are happy when the

answer comes back, “Tbilisi”.

But it is so dark. Coming into Paris and Istanbul, the

cities were filled with a flood of lights. This is in stark

contrast. We are not in Kansas, anymore. Toto!

We are met by a man hired by the Embassy to drive us to our

apartment. The car moves silently across bump-filled roads

in semi-darkness, then on narrow streets until suddenly we

stop and are led through a dark entrance with dirty, peeling

walls and broken steps. It is a concrete dwelling with

multiple stories, pre-Soviet design I learn later, but there

is little at this time of night to identify it. We walk up

one flight of steps, open two massive steel doors with four

keys, and are greeted warmly by our landlady, Landia. She is

in her eighties and speaks no English. Our tour person

translates, somewhat. The inside is in stark contrast to the

walk up the steps. It is bright and large. In many ways, it

is our first lesson in learning about Georgia. Never accept

the outside for what is contained inside.

The ceilings are fifteen feet high. There is a crystal

chandelier in the living room. I feel like Gauguin or Degas,

stepping into the 19th century with Anne as my

mistress/model beside me. Everything is old, antique really.

There are two single beds in the master bedroom and the

total apartment is bigger than our townhouse of 1600 square

feet in Waco, Texas. We are so tired by the time everyone

left that we do not have the energy or desire to eat the

bread, cheese, fruits and snacks stacked in the ancient

Russian-made refrigerator.

We sleep like the dead until 9:30 a.m. (all four and half

hours of rest) but we are comfortable, although apart for

the first time in over forty years of marriage. Our bodies

are still exhausted from the trip but our heads are alive

with things that need to get done in the next day, week,

month, and year. We stand in the middle of the apartment,

looking at the 100 boxes of books and other things sent by

American museums, architects, and artists for a Collection

which will represent American art long after I leave in May.

We sit looking at the piles of work and wonder what is to

come next. It is a scene that will be repeated often in the

next nine months.

When we awake, it is to a Rococo bust of a lady, a ceramic

eagle from the 1800’s, some art nouveau vases on top of an

antique twelve foot by nine foot wardrobe, vintage late 19th

century. Now, the windows are open and light is beginning to

own the darkness. Bread, cheese, fruit, and bottled water

are a welcomed breakfast. This is a ritual which will become

routine in our stay in Georgia. I take my morning pills and

go to the study, which is quiet and piled with boxes. I

begin opening the gifts from American architects, museums

and Texas artists. It is Christmas for me. Surprise after

surprise. Michael Graves sent his book, Robert Venturi sent

six and Stephen Holl sent his ideas about what the future of

architecture should be. Holl has just been featured in Time

Magazine as “Architect of the Decade”. The Museum of Modern

Art in New York, Hirschhorn Gallery and Sculpture Garden,

Houston Museum of Fine Arts, New Orleans Museum of Art,

Newark, Albright-Knox, Honolulu, more and more gifts are

opened. I am filled with wonder on America’s help in this

adventure in a new democracy.

Magda, Nata, and Georgi come from the American Embassy of

Georgia to tell me about my duties which will start in

October. I had been told September before I came but it was

not clear even then. I knew about classes at the Academy,

the National University, some other lectures and session

with non-governmental agencies, working with museums,

secondary school talks, and then Nata says, “Oh, would you

mind going to Kutaisi to represent the United States at an

International Artists Workshop where you paint and lecture

for the month of September?” All kinds of questions filled

my mind but all I said was,”Yes, that would be fine. Of

course, Anne goes too.” “Of course, you will be joining two

Russians, two Germans, one Greek, one French, 10 Georgians

and some other artists. All the painters and graphic

artists will complete at least five works, three going to

the Georgian Artists Union and two for the artist. The

sculptors will just complete one work to be left in

Kutaisi.” A thought did appear, “We have just arrived on the

23rd of August and now we leave again on the 27th!”

but I am elated. I came to Georgia to meet other artists,

work at my own painting, and teach new ideas. This is that

opportunity.

In the evening, we try to find a restaurant that I wrote

about before coming to Georgia (my editor wanted all my

Letters from Tbilisi in his hands three months before

publication therefore our first impressions of Tbilisi were

described through images from the internet). Now, we wanted

to go to make the article true. We knew that it was outside

of the city. What we found is that six restaurants had the

same name therefore we choose one below the patron female

saint who welcomes visitors. Her statue is perched high on

the mountain (which I learned later to call “a high hill” in

contrast to the Caucasus). The restaurant is on the second

floor, a large room with numbered tables set up for groups

of ten or more. We look at each other with the expression,

“Did we find a hall which only caters to banquets?” There

were two groups of men already seated at tables, toasting

and singing. We seemed strangely out of place and time, two

alone Americans being seated at a table which was set up for

twelve. “No, it is all right,” said a young waiter, “we are

set up for smaller parties.” Strange, I thought later, that

he should use that word “party” for that is what the evening

became. We order a full bottle of Old Tbilisi wine (thinking

that we had only ordered half a bottle but learned quickly

that nothing comes in halves in Georgia) and settled down to

eating some of the best food of our lives. The supra, an

ancient toasting and drinking ritual while eating, which has

symbolic and real value to keeping Georgia Georgian, was in

full motion at the other tables and it did not stay at one

table. Toasting was done between the tables, across the vast

hall and around each table. The live entertainment was

professional and marvelous, soloists and singing quartets

with piano/organ and a drum. The voices of the singers

rivaled any opera stars.

At some moment in time, another birthday party came in; a

bottle of wine was presented from one table to another,

although it was obvious that except that they were all

Georgian they did not know each other before that moment.

Time was at a human pace. Two and half hours passed

enjoyably, listening and eating. Then a major figure came

into the room, passed from table to table, surrounded by his

subordinates, and slipped away as a whisper in the joy of

the night. Anne nudged me and said, “Godfather”. We finished

the last of our wine, ate the last delicious morsel of food,

prepared to leave when a new bottle of wine of Old Tbilisi

Red was presented from a man at the table in the corner. We

blew each other kisses, a universal symbol that transcends

spoken language, and settled back for a longer evening. We

had never drunk two bottles of wine at one meal.

Later I found a waiter who spoke some English, got some

Xerox paper to draw on, went over to our host’s table and

drew his portrait. He had a strong, robust smiling face. We

were no longer strangers in that moment. People at the front

table, seven men and one exquisite young woman in a red

dress, were gathered around an enormous, lighted birthday

cake which had been brought to the table with great

ceremony. The men got up to dance together. Finally, the

birthday lad and the young woman in red danced to a slow

Georgian tune. It was hypnotic; the two of them were ballet

dancers in their own realm on a stage made just for those

two. The graceful movements of their hands, arms and

intrigue steps were a thing of pure joy. I had never seen

such beautiful dancing except on a professional stage and I

had looked the world over for this kind of beauty. Matisse

would have envied my vision at that transfixing, magic,

extended moment. Others cut in to dance with the lady in

red, then she sat down and two men locked arms in dance.

Finally, our objectivity was broken when some young men

asked us to join in the dance. We did. It was not the beauty

that I had seen with the lady in red and the birthday lad

but that was not what the party had asked us to do. All they

ask was “join in the dance”.

When we left the hall that first night in Tbilisi, full dark

night had come once again upon the city and this new outside

world. It was the same dark that we had encountered when

driving in to our apartment for the first time but somehow

it was totally different. Now, the dark was a cloak that was

worn with a smile, warm and friendly. We had been the

“honored guests” in this new nation.

It is Sunday now, the day before we leave for Kutaisi. I go

to the lot behind our apartment to unload our trash cans

into the four large containers. I just make it in time as

the garage truck is loading. The men are so courteous and

helpful. I have two loads of empty boxes and they help me.

They carry the loads and somehow communicate that “Is that

all?” As I walk back to the second floor, six men work on a

disassembled motor, another dressed as a chef unloads fresh

meat from the trunk of his car and cuts it on a large tree

cross section, and two boys play war games with toy machine

guns and a toy rifle. Each bobs his head, “Good morning,”

except the boys who are winning their own imaginary war.

Later, I find that the taxi drivers are tolerant of

“non-Georgians”. I give them another address for one of the

six restaurants with the same name and they try to make out

where we want to go. None speak English. We speak no

Georgian. One driver went in the opposite direction at first

until he realized his mistake (or our mistake in writing the

address) and still we were charged the normal 5 lari ($2.50

USD).

October, 2001: Letter From Tbilisi: In truth, this

letter should be titled Letter from Kutaisi, Georgia. After

arriving in Georgia, we were invited by the Fifth Annual

International Plenary for Artists to come to Kutaisi and

paint five works of art, two for myself and three for the

Georgian Artists Union. I am the first American artist to be

invited and participate. It is such an honor and opportunity

that I jumped at the chance. Anne and I would see parts of

Georgia that no Fulbright Scholar or American had seen

before and at the same time live and work with twenty of the

best artists in France, Greece, Germany, Russia and of

course Georgia (10 sculptors and 10 painters/graphic

artists). As an added gift, Anne and I were asked to be the

guest of the Governor (and his wife Dea) of 14 Western

Georgia districts, Mr. and Mrs. Shasheashvili..

Nine of us left Tbilisi by bus, sent by the Municipality of

Kutaisi, the old capitol of Georgia. To say that the roads

in Georgia are bad is the largest understatement that I can

make in these letters. It did not take long for the beauty

of the mountains and valleys to make us forget our

backsides, the luggage sometimes coming down the aisle and

the slalom-driving to miss the potholes that could stop our

adventure. Also the warmth and comradeship of the other

passengers makes up for the lack of smoothness. We stopped

to eat warm bread, khachapuri (a bread with cheese inside)

and fresh cheese that rivals any in the world. We drove into

the towering mountains for five and a half hours before

reaching Kutaisi, a much smaller city than Tbilisi. Cameras

for television and newspapers greeted us, as well as the

Governor, the Mayor and other district dignitaries. It does

not take long to realize that one must wear several hats at

these international events: artistic, political and social.

It takes a juggling act to shift roles but it is essential

to understanding the situation.

Soon after the individual and group photographs were taken,

we were escorted by the Governor’s driver to a modest home

at the outskirts of the city (it had been his parent’s

house) and first met Dea, his wife, who would become a

friend and companion over the next month while we were in

Kutaisi (which ended up for only two weeks since we took

side trips to places where no Americans have gone, the high

mountains). That night we were the honored guests at the

annual religious ceremony at the 6th century

reconstructed church high on the mountain protecting the

city. Everyone walked behind the golden icon of the Virgin

through the winding, cobblestone streets to the church.

Later, we had our opening banquet which started at midnight

and ended at 7:30 a.m.with wonderful food, drink, toasting

(it was our first real extended experience with the Supra,

the Georgian ritual of toasting by the men), dancing and

singing. We only made it until five in the morning but when

we left the party still was alive and spirited. The Governor

was the tamada (the orchestral leader of the Supra) and was

brilliant to watch, making sure each of the 40 participants

were honored, had a voice and given the correct time to

speak and be heard. He had to mix humor and wit with

seriousness, music and dancing with the toasting. It was

masterful to watch. And also he had to drink more than

anyone at the banquet since he was the leader who honored

all. I do not know many American leaders who could shoulder

his role.

I attempted to figure out the schedule but only found that

we ate at nine, three and nine o’clock because the sculptors

needed the light to work. Many of the first few days were

spent with a “hurry up and wait” pattern. When Dea asked us

to go to the Black Sea for the day, it was a welcomed break.

The sand was black, the water warm and the company

delightful. On returning I found that I was leaving the next

day to go to Kharagauli with two other painters and Anne. It

was a rare and wonderful trip, high in the mountains, filled

with breathtaking scenery, visits to artists and farmers who

not too many foreigners get to meet, and welcomed by a

hospitality that is second to none in this world. We ate at

Sasha’s small house (no more than fifteen feet square) and

he gave us all that he had (with the Supra of course). The

poverty in Georgia is widespread but the pride in country

and giving to an “honored guest” is a long and respected

tradition. One plate is always left empty just in case a

guest might arrive. I got to see David Sakwadzef, the

district manager of Kharagauli, ride like John Wayne, tall

in the saddle and comfortable on a horse. I finished eight

paintings, after driving over non-roads, fifteen streams and

car-size potholes where the water came halfway up the tires

of our Russian army jeep, so I can take a day off here and

there to visit other magnificent places. The economy and the

road are poor but the people are rich in spirit and live in

one of the truly beautiful countries of the world. The

economy will change. New leadership will make sure it

happens but only because they can build upon a foundation of

centuries of tradition, a fierce pride in nation and the

warmth of a people that overcomes many adversities. I will

miss Kutaisi when the final exhibition opens and I return to

Tbilisi for teaching but I will plan to come back during our

year because friendships have been made.

Kutaisi, Georgia: The International Plenary Workshop for

Artists and Sculptors:

A rooster crows in the distance, returned by another cry in

the opposite direction, a cow moos to the morning, a few

sounds of children break nature’s symphony or add to it, and

the flapping of pigeon wings are all the sounds that great

my awaking in Kutaisi, Georgia. In the distance, the city’s

cars made a soft rumble as this city of 300,000 awakes too.

The sight of a straw hat appearing over the hedge in the

distance tells the story that the farming community has been

awake long before my stirring. Now, a few voices join the

concert sounds, accented by the chirping of crickets.

Visually, the mountains ring the city. I sit on the rough

concrete balcony of the Governor’s house and feel the cool

morning breeze wash my skin. It is 9:00 a.m. For me, that

seems like getting up late, but if you party collectively

until 5:00 a.m. then this is early. The Kutaisi Georgians

are the crown princes of partying with speeches and toasting

(the supra), food, food, food, singing, dancing, more food,

drinking (no glass goes unfilled) and music (a trip of

voices, saxophone, piano and violin). That was the opening

banquet held by the Georgian Artist’s Union and the Governor

of the Western Section of Georgia. It started at midnight

after a religious service at the 11th century

church (started construction in the 6th century)

where Governor Shashiashvili and priests presided. The

city’s icon of the Virgin Mary was carried up the mountain

(“high hill”) to the cathedral without a roof. Anne walked

the whole way with the procession, up the winding,

cobblestone streets. I drove, resting my bad knees.

We arrived to a press blitz, had pictures taken and were

whisk off to the Governor’s house. His wife Dea greeted us

and we ate the first of two meals before the midnight

banquet. As an artist and a man, I was struck by her beauty

and graciousness. I tried to draw her but it was not even

close. I had brought a tiny sketchbook for portraits where I

would draw the face and the model would sign in Georgian and

English. I did not ask her to sign that drawing. Later, I

would do another. I did start a small series of portraits of

the other eight artists who came with us in the bus. It is

my visual memory devise to learn names and tie them

permanently in my mind with every feature. I drew some other

portraits at the banquet last night.

Anne tells me that breakfast is “prepared”. Breakfast is

never “ready” but it is a major preparation. As I leave the

balcony, the city comes more alive against the panorama of

the breathtaking mountains. I hope to learn the schedule for

the artists today but I have learned already that “things

come as they come in Georgia”. There are things that are

sure: there cannot be any other people in the world who work

so hard for so little and party so hard for much!

I meet with a group of artists for lunch. We discuss many

things through two or three languages. The artists have

impressions of America that differ from mine. The discussion

centers on our “old democracy” and their “new emerging

democracy”. George, the sculptor, points out that each time

the president changes here the system changes whereas in

America the system stays the same and the man at the top

changes. We discuss the “corruption” of government in

Georgia. We discuss how the infusion of American’s dollars

into any economy that is just beginning creates the idea

that “money will solve everything”. One fear that George has

is the environment. How can Georgia come into the 21st

century and still keep the beauty that is this special

place?

After a week of hard painting, we drove to the Black Sear

and black sand with Dea and her children, the two German

artists and our driver from the Governor’s office. After

laying in the shade, with the roasting sun turning the sand

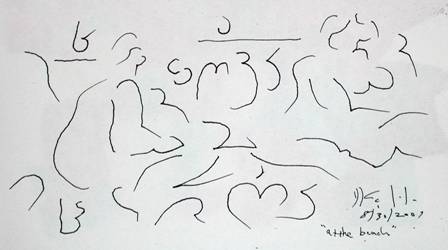

to hot coals, I ask Dea’s daughter, Nini, to write “sky,”

“water,” and “sand” in Georgian and I copied them upside

down (a trick I learned when studying counterfeiting of

signatures). Now I must put them back together in some kind

of structure that pleases me and captures the love that I

have for the visualization of this special alphabet (being

one of the fourteen languages of the world and only used in

Georgia). I drew:

As the heat intensifies and the burning sand stops all

walking in bare feet, a vendor comes by. I ate two ears of

corn as a snack. It was so fresh, tasteful and delicious

that I think “it is a shame to only serve it with a meal as

we do in America”.

After another bumpy ride home where our backsides ruled our

minds, Anne and I wish to walk a little in Kutaisi. It is

raining. We have no umbrella and are soaked as we journey to

the studio to get instruction for the next week. We are told

that we “must” go into the mountains for “five

days”. I expect Renoir or Monet to bring canvases for

the extended outing. We should ask Seurat too, I think. Oh,

how the thinking about art and contemporary concepts are

non-existent. Down below the two Georgian artists bring

canvases and rolled paper. This is a far concept from my

laptop images from my digital camera for details and my

sketchbook for concept images.

The way that I work is gather information. Actually, that is

how Renoir, Monet and Seurat also worked except that they

did not have a laptop or they would have used it.

I gather information in the quickest way possible- sketches,

photos, color studies, ideas in words, and then I come back

to use this material which emerges from the ideas in the

field. Reality has changed since the 19th

century. Not Nature herself, but how man collects

information. It is no longer reality which is only outside

the eye but also what we know, what we dream and what we

imagine. Sadly, that kind of thinking is called “foreign

influence” and “liberal” and “American”- even when a

Georgian artist does it. For now, sitting on the balcony,

waiting to leave for the mountains, we wait, we wait, we

wait. There is no schedule. In Georgia, it has not been

invented yet.

Kharaguali, Georgia: We had dinner at the Kharagauli

district manager’s home. Once again, the food is delicious

and abundant. We toast to America, Georgia, family, parents,

grandparents, art of Georgia and the world, the artists from

all over who came to Kutaisi, Kharagauli, peace,

Shashiashvili and a special toast while drinking from the

“singing goblet”. The goblet is filled and as you drink it

slowly song comes from it, a long Georgian chant from the

past. The competition is to drink until the song is almost

over. It takes practice and the more wine that you drink to

practice the worse you perform. David, the manager, has five

children, one son and four daughters. The girls sang three

Georgian songs as we ate and they sang like angels. When we

returned to the hotel room (kept for those who came to give

or get from Kharaguali), my head was light as I sat on the

edge of the bed but my body was too heavy for the weak

boards holding up the mattress. It crashed to the floor so

we slept in the other single bed. There was no electricity

so we lit a candle. During the night, since the holder for

the candle is some kind of plastic that is disguised as

metal, there is a fire in bathroom. Anne puts it out as I

sleep.

High in the mountains (much higher than we

went yesterday in a standard jeep) in the chill air,

in the home of an artist, in the village of Leg-wani,

we sit around a carved table, nine men and Anne,

surrounded by art inside and beauty without.

I can see why this talented man returned to the

mountains to work.

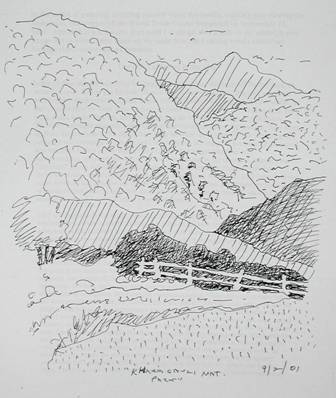

We drove on and come to a point as high as I thought we

would go. We arrive at Borjami-Kharagauli National Park

(halfway to “Iron Crest”) which is only part of our journey

that day. “The road gives out,” we are told. “Iron Crest is

six miles further up the

mountain. We have crossed fifteen white-foam,

rapidly-rushing, shallow streams and countless holes in the

dirt “road” filled with water that come halfway up the tires

of our Russian army jeep. The pride that the Georgians have

in their land is everywhere. Java, a Georgian painter from

Kutaisi, started a canvas using a clump of trees as his

subject. I paint a color study. No one paints the grandeur

and majesty of the towering rounded mountains. One can see

where the curves and rounded letters of the Georgian

language come from. Later, we stop at Sasha’s small farm.

All the houses and work sheds are hand-built with simple

rough wood. His home is elemental with three rooms- two for

sleeping and one for general use. One of the sleeping areas

doubles as a place to eat. Sasha and his neighbor, Robert,

give us the best that they have: bread which they bake

themselves, another bread made from potatoes, homemade

cheese and wine, and khachaburi (a bread with cheese

inside). We eat and toast for an hour and a half with Sasha

and Robert speaking passionately about Georgia’s future. As

Robert says, who is in his late seventies as is Sasha, “All

we have here is hope.”

The contrast between the unbelievable beauty of the

mountains of Kharagauli and the believable poverty that is

so obvious is something that all Americans should see. Even

the man with so little (except hope in the future) shares

all he has with strangers. There is a wonderful tradition in

Georgia of leaving one plate empty at the table for the

guest which might come. There is so much richness in the

daily life of Georgia that I want to drink it all in.

Back in Kutaisi, we go to visit a woodcarver’s collection.

He died four months ago. When we arrive, there is no light,

no electricity therefore we view each work by candle light.

It is an enjoyable way to view works of art. You have to

concentrate on each creation and remember its detail to

compare it to the next work of art. Later, the lights came

on, the Governor’s wife, Dea, called the electric company.

The next day, we visit the Kutaisi Museum and the

electricity goes off again in the middle of the viewing. We

have to feel our way to the exits in the dark. One of the

smartest things that Anne brought was a flashlight.

Bagdati, Georgia: at a mineral springs retreat built by the

Soviets and now rundown but used by thousands of Georgians:

I feel rested but it comes in two to three hour sequences.

The bed is firm, the pillow a little less than concrete with

a soft cover, the wood floor holds together by the dirt

between the boards which tip up as you step on one end, the

bathroom…well if you sit the commode your knees are under

the sink, and the water in the sink never stops running. In

the mountains, there is no short supply of water. We have no

towels, but luckily we are learning and brought one. Life is

at its elemental again. Everyone says it was better under

Communist rule but no one speaks of going back to that kind

of life. Our friend Ato, the painter from Kutaisi, has a

gallery in Milwaukee where he sells a few paintings a year

that keeps him, his wife and a child, his mother and an aunt

surviving. I have learned that is the key word in Georgia-

“survival”, except for the politicians and a few businessmen

(some say ex-Communists who got theirs before the change

happened in the country), all driving BMWs and Mercedes. I

am asked by a reporter from Batumi, a city in the lower

southeast corner of Georgia, “What do you not like about

Georgia?” I sidestep the question by asking her, “What do

you not like?” The young highly-educated reporter says, “The

bad roads, no electricity, no water, no hope at times, and

my salary, 30 lari a month. How can anyone live on $15.00

USD a month?” “You have answered your own question then,” I

reply.

Yet again, in all this, the people love art, country, their

traditions (which have survived through occupations by the

Persians, Turks, Mongols and the Communists from Russia),

their unique language, and one of the most beautiful spots

on the face of the earth (although only seven percent of the

earth is good for growing things). There is a zest and true

love of life which is refreshing while at the same time

there is a deep sense of seriousness. The colors of this

land are black mixed with bright red and white. It is Death,

Blood and Hope, which are the colors of the Georgian flag.

To Color and Form

September 2001: Hundabe Valley, Kharagauli: “Creation of art

is not a duplication of what most people call “reality”- a

distant view. It is close and far, what I see and what I

know is there, the color on the surface and the color coming

through the surface, and what is in the distant view and

what is in the air between the eye and the object.”

To mountains and Landscape:

In the midst of painting, drinking mineral water for

health, walking and viewing the mountains, the tragedy of

the World Trade Center happened on September 11, 2001.

Although it was several days until I could get this article

to my editor, it was important to write it and make up my

mind how my painting would reflect my feelings about

terrorism and freedom.

Cut Off, Yet Seeing From Afar

In the 20 days that we have been in Georgia, the electricity

has been off for ten days, no water for seven and no gas for

four. Here in the mountain region of Bagdati, a mineral

water resort (since most Georgians cannot afford medical

care), high above the world, we had no electricity for three

days. There is no email or internet and all cell phones do

not work at this height. One can call out but the line for

the one telephone is prohibitive. Therefore last night when

the lights went on and the candles were put away, a cheer

went up from the hundreds in the dining hall. Later we went

up to view the one television (the language was Georgian of

course) and I saw in horror the image of the burning,

collapsed and torn twin towers of the World Trade Center.

The image was clear and understandable, although the only

word that I understood in the Georgian subtitles was

“terrorists”. (some words bridge both languages). I watched

the images from the universal screen, the television, and

found the anger rising within me. All I knew was that some

terrorists had attacked my country (two cities, New York and

Washington) with the weapons of international terrorists:

fear and violence. It was planned for maximum television

coverage and maximum emotional impact.

I did not sleep much that night, replaying the images in

same manner that that the fourteen-inch screen had done

earlier. The strike on the twin symbols of America’s

economic power had been high up, telling us that no place is

safe now. Still not sleeping, I reviewed the two pieces of

information and thought that I might not get more data if

the pattern of no electricity continued (it did). My major

thought in the night, so far from America, was: “We cannot

allow these fanatics of fear to change our way of life, the

freedom that so many through the years had died to defend”.

One of our strongest weapons is our freedom itself. They

attacked our basic resources: world trade and business, our

symbol of Democracy (Washington) and our elected and

military leadership. We may not be free from caution or

safeguards but we can be free not to choose fear as a

response. My Georgian companion asked, “Why did your country

not kill the terrorists, wherever they hide, before they

acted?” My Georgian was poor and his English was not up to

my complicated attempt at an answer. In the middle of the

night later, I not only wanted to wipe out the leader behind

this act of violence but wipe out the fanatics’ names - no

identity for history, no recognition and certainly no

television prime time. George Orwell taught us that those

who write history create history. We Americans hold

individual life and property as a precious gift. We are

shocked at those who throw away life as if it does not

matter. It is strange having only bits and pieces of news,

or worse no news since the electricity is always

questionable. As a people and society, Americans have

instant everything, including more news than our minds can

handle. Here, I have minimal or none. And when it does come,

it is through limited translation.

In the midst of a long, dark night, I asked myself: “What

can I do as an American abroad to support our belief in

democracy and freedom?” The answer was swift and clear. I

came to Georgia to tell others about America, especially

American art and architecture. Right now, in the mountains,

I am the American representative at an International Plenary

of artists from many nations. I will paint with the

brightest, strongest colors that my freedom allows. I will

not give in to black and bright red, death and blood.

Later, many Georgians came up to Anne and me, touched their

hearts and said, “Sorry”, one of the few words in English

they knew. I replied, “Thank you very much,” one of the few

phrases in Georgian I had learned. Here, a people with so

little extend to me- the only symbol of America in these

remote mountains- their sorrow on our national loss. I am

moved deeply. After a long wait and help from a Georgian

artist, I talked with the US Embassy about our safety and

was told to stay in the mountains a few more days.

Therefore, we remain at a place where there is little or no

communication with the outside world and the one television

for two large “hotels” worked only a few minutes to give me

a lasting image to ponder. I would say for all of us to

ponder.

After waiting in line for the one telephone for over 1000

callers, I contacted the American Embassy of Georgia about

our safety. A special meeting was being held in Tbilisi for

the American community in Georgia but there was no way that

we could make it on time from the mountains. Also, we were

told by the Embassy staff, “Stay where you are for a few

more days. You are safer there than here.” Therefore I

returned to painting and writing in my daily journal. I

reviewed what we have seen and create two other segments of

the December exhibition.

To Soaring and Joy

“Birds fly in great sky

circles of freedom

How do they learn this?

They fall

And having fallen

They are given wings.”

“May the Beauty we love be

what we do.”

Jelaluddin Rumi, 13th

century Islamic, mystic poet who believed that we all are

brothers.

I discuss in my journal that relationship of color and

form to the mountains. Also I think about the relationship

between the abstract qualities of these natural structures

and the forces that are at work within me. Later, I found

these words by David Kakabadze which I will use for this

celebration exhibition:

To Color and Form

In 1921, Kakabadze wrote:

“Art should not present what exists, but what is possible to

exist.

Art is as solid, as more it

describes unexpected events.

Possible plastic art, which

does not remind us of existing natural shapes, but by its

inside character inspires possibilities of nature.

Plastic forms exist, without

telling any contents.”

I find today that I am a

brother to Kakabadze in spirit, not really separated by

eighty years. I keep a photograph of him, taken in 1950,

that shows his love of life and Georgia. I celebrate his

joy.

As Anne, Java, Ato and I walk down to get the “after meal”

mineral water, an image appears across my mind’s visual

memory. I am six. It is 1938. I had to tend the tomato

garden in our backyard and I look forward to eating liver

pot pie for dinner. Many men are out of work. Fortunately,

my father has his job as a milkman. Everyone is poor so no

one knows that they are poor. Later as I grow up I decide

never to eat another tomato or a cucumber (also growing in

that tended garden) as a protest again that time in life

when that was all that we had at breakfast, lunch, dinner

and as snacks. In Georgia, I again eat tomatoes, cucumber

and, sometimes, liver!

I am reading Edward Hall’s “Beyond Culture”. It should be

standard reading for any Fulbright Scholar. We see daily

examples of the clash between monochromatic-time (Western

ideas and schedules) and polychromatic time (the Georgian

hold on the past and non-scheduled activities, even when

scheduled). Our waiting time in Kutaisi is understood now,

frustrating but understood.

Again, back in Kutaisi, we attend a Georgian play. The

dancing and singing are wonderful. The play is a symbolic

and predictable saga of Georgia’s march from Communist

“blindness” to freedom. It was written in 1987 and banned by

the Communists. As a critic, this banning of the play is the

only reason that it lasted this long. My German painter

friend, Claus-Peter, and a Georgian artist only could take

one act. We stayed the whole time. You can learn much even

from bad plays. I am writing this on the porch of the

Governor’s house, where five families live, with no

electricity or water again. This condition has continued for

the last eleven years since independence. In some ways, the

Georgians are still blind to solutions and accept the

circumstances. This real play will also last until there is

a cultural outcry and the blinders are taken off. Drinking,

toasting and talking will not change a situation of no

electricity and no water. Only action will make a difference

and that means figuring out how to obtain the political and

financial resources to create change. There are those who

see, as there were in the play, but they feel that nothing

can be done in a corrupt system of government. And some, who

prosper by the misery, do not want change.

More reading of Edward Hall’s book gave me an insight into

the lack of color in this society. Hall discusses the

working of the human eye: cones in the center which are the

tools to make fine color distinctions and rods further out

which distinguish movement. If you are being confronted

daily by things (automobiles, strange characters, etc)

coming at you from all sides at once, you use your rods more

than the cones. This society has always been attacked from

all sides and still is. Walking the streets, cars come from

all directions without reason or a system. I have found that

stopping for a red light is only honored by some, sometimes.

Again, Hall gives me more insights. Anne read me a section

about the Arab’s “spite walls” in Kuwait. In two instances,

an Arab was offended and took years to buy the land around

his victim’s home. When the land was all purchased, he built

a high “spite wall” around the neighbor’s house so that the

offender “could not see the sea or the world around him”.

That is the intent of Osama bin Laden, using his terrorists

instead of a spite wall, to America today. He is trying to

change how Americans see the world around them. He is

attempting to wall in freedom.

It is another early morning, just me and the roasters

crowing. In the east, the warmth of the colors of morning

begins to fill the sky. I did not drink last night at the

supra, a five-hour banquet. As I see beggars on the street

and people living on bare existence, it is hard to watch the

abundance of food and drink that is laid out at each banquet

of those in positions of power- politicians, lawyers,

educators, doctors and others. We have had supras in Kutaisi

with all of them, in fact 40 supras in 30 days. I believe

that I understand the guest-host relationship and traditions

of Georgia. As the vice Governor said last night, “If you

are the host in the house, then no matter the relationship

with your guest- friend or enemy- it is an iron-clad

tradition that you offer the guest wine and food while he is

under your roof.” That is a marvelous tradition and a model

that could be used for the world, but the national scene in

Georgia is such that the people are suffering. Aren’t the

people of Georgia a guest in the house of the politicians?

True, a nation must take care of the stranger but I see

estranged citizens becoming strangers in their own land!

Edward Hall writes, “Man has a personal relationship with

everything. What one needs from life is power, but that

power can be used or find its way only in certain

directions, which are set by the karma of the individual.

Hunters relate to one cluster of particular substances,

while men of knowledge have another set.”

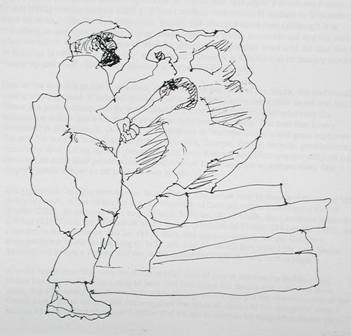

On the day before leaving Kutaisi, we were asked to visit a

dance class. We went to the where the sculptors work and

wait for our guide to the dance studio. No one comes at the

appointed time and just as we are ready to leave, a voice

behind us says, “The dancers are now ready.” We are lead

into a small room, hot with no air conditioning, with about

thirty young dancers waiting on benches as we come in. At

once they applaud our entrance and stand up. We are the only

audience and they are magnificent. I see where the great

tradition of quality dance in Russia and Georgia comes from-

two seven-year olds hold themselves erect and then move like

seasoned, professional, ballet performers. The headmaster

(and he was that) holds a stick and is not reticent about

using it to show correct form and a straight back. Again

quality comes from this kind of enforced discipline. He also

kisses and hugs the children when they excel.

That evening we drive with Dea and Governor Shashiashvili in

his Mercedes to the Conservatory for a concert. The music

again is superb, first class in any culture. The conductor

is from Tbilisi and has spent a year conducting in America.

As the light dimmed outside and no electricity inside, the

next to last piece by a Georgian composer is performed by

candlelight. The last piece of the evening has to be

cancelled. As Anne says, “It almost brings tears to see this

serious pursuit of excellence in a country where they cannot

afford electricity for excellence.” Our hearts go out to

these fine musicians who make little or no money as a

professional and to the audience, packed to the standing

room, who endure the heat and concert by candlelight. Just

when I think that I see and understand Georgia a day happens

like this, filled with wonder and superb beauty and tragedy.

Yesterday, I taught a two hour class at the Kutaisi State

University to about thirty students who were studying

English. My talk was called “Freedom and Creativity”. We

played creative games, audience participation, discussions

and I gave a straight lecture. Some professors who attended

said that my style was different than what they were used to

under the Soviet system. That system had been a formal

lecture and then a few questions. I gave no less information

to them but not a formal talk without their participation.

Learning for me is a joint activity between teacher and

student where the object of the teaching is to make each

student his or her own teacher. We discussed Georgia’s

problems with democracy and I told them right off that

America or anyone from the outside could not be the

solution. They could be an asset, an aid, but never a

solution. I was asked what I thought were the resources that

must be in place to make change. I was reticent to say, only

being in Georgia for a month, but I was pushed to say what a

consultant might recommend. I said, “Leadership, vision,

building upon natural resources, the use of the vote to oust

elected official who do not serve the people, the use of the

vote to create change in the people’s best interest, and the

use of outside sources that need Georgia’s riches.” They

asked what to do about corruption. I told them that it was

an internal decision that only they could make with the help

of their elected officials. One girl said, “Our elections

are only the show of democracy, not true voting.” One boy

said, “We have no models. How can we solve the problems?” At

this, I laughed and added, “Who knows one resource, which

could be a solution, which Georgia has in abundance?” After

a short silence, one girl said, “We have water.” “And all

over the world, water is used to make what?” “Electricity”

was the choral response. I told them about meeting a farmer

who had harnessed the power of a stream in the mountains for

his saw mill. He had electricity all year round for the

saws, sanders, grain pounders, and enough left over to send

it to his home on the mountain. He was never without

electricity. He had their answer in microcosm. I left after

signing autographs (a new experience for an American

teacher) and went to the opera house for a final performance

before we left for Tbilisi. It was like a Kennedy Center

tribute to performers but instead of six artists being

honored it was one. She was a singer who had worked at the

Met. A younger opera star, now singing at La Scala in Milan,

gave a magnificent tribute in song, and accented it at the

end with flowers for the honored guest. Anne and I attended

the final banquet for the grand lady of the opera. It was a

banquet for one hundred friends with toasts, food, singing

and dancing. I drank water and no one cared. It was a

glorious day in a series of days that can be called “best”.

Driving back to Tbilisi in an American Embassy car, I

considered what I had learned in Kutaisi. I had seen

Georgian social, country club life, the political world from

the home of its leading politician in Western Georgia, the

problems of the artist in this politically-charged setting,

small villages in the mountains, farmers who gave all that

they had to a stranger from America, and had seen places

high about the valley floor that few Americans have had the

privilege to experience. I attended dinners in a cramped

setting on a mountainside in a hut for one which held four

people, in artist’s homes, conferences of doctors, lawyers,

scientists, educators, performing artists, children’s school

administrators, University professors and many, many more.

We attended supras until the wine became too much. We lived

with the Governor and his lovely wife, Dea, for a month. We

do not even live with our children now for that long. We met

business leaders who are trying to expand the bounders of

Georgia through commerce. We knew judges who painted,

painters who were trained as scientists, leading doctors and

educators who recited poetry at the supras. And we had seen

Georgia’s common man close up in the city and the mountains.

We were the official Americans at every event we attended

(two or three per day). We were the only Americans in

Western Georgia for that time. I was interviewed over twenty

times in the thirty days. We learned about sacrifice,

dedication, pride, tradition and the Georgian love of art,

all arts. I read Edward Hall’s “Beyond Culture” as I was

experienced a culture beyond my own and it was the right

moment for that insightful book to give a framework and

perspective on what we saw and felt. Mostly, we survived,

endured, learned, enjoyed, transcended together and got the

best preliminary education about Georgia that we can be

imagined. When we drove into Tbilisi, both Anne and I

commented that this time we are coming in with a fresh

attitude. This is now “home” for eight more months and the

darkness is not as frightening as the night we first came

from the airport.

Shortly after returning to Tbilisi, after my month of

work in Kutaisi, I was asked to have a December exhibition.

Almost at the instant when the idea was presented to me, I

began to think in terms of the things that I learned in my

first few months in Georgia and the one thing that stayed in

my mind was the supra. For me, it was more than a drinking

ritual; it was a way to celebrate all those things which are

important in the life of a country and an individual.

Therefore, the idea of An American Supra started as I

considered all the resources that I use in my art work and

feel are important in life. Groups of paintings were

dedicated:

To Play, Childhood and

Family

To Love and Freedom

To Georgia and America

To Icons and Tradition

To Mountains and Landscape

To Color and Form

To Soaring and Joy

To Death and Those Who Have

Died

To Heroes (Like David

Kakabadze)

To Life and Being Truly

Alive

Since this Fulbright (to

Georgia) was my second and the first was 36 years ago, two

sections of this exhibition dealt with themes that I had

explored at the time of my first Fulbright to Taiwan; Death

Is All The Time, a book painting which I created in 1963 but

published in 1975 and a book I purchase in the early 1960’s

that has sustained me for years in my creative work, Les

Dejeuners by Picasso.

To Death and Those Who Have

Died

Shortly after my marriage in

1957, I learned that my wife’s grandmother had lost 44 of 48

relatives while under the Nazi regime in Hungary. I acquired

army photographs of the concentration camps and studied them

for several years, not being able to divorce my feelings

from the forms that jumped from the pages. In 1963, I took

time off from teaching to give full attention to creating a

work of art in Phoenix, Arizona that dealt with all the

aspects of death that I could think of at the time: from

microscopic to macrocosmic death. I worked twelve to

fourteen hours a day, completing over 2500 drawings in one

year, and completing 169 finished drawings for Death Is All

The Time, a book painting (which I finally published in

1975). During the working on this work of art, Jack Kennedy

was murdered in Dallas. Since I knew him, he was included in

the work under the title “Death of a Young Man Murdered”.

The intensity of the work in 1963-64 forced me to examine

the opposite point of view. That work was called In Summer

When Butterflies Don’t Even Die. As artist in residence for

Washington State University in Spokane, Washington, I

exhibited all the drawings from these two series in 1965 (a

little over 300 works of art). They caused a stir in the

community. I decided to wait to exhibit them again until the

times were able to see them for what they were: examinations

of two extremes in life. Much of the work that has been

completed since that retreat in Phoenix has dealt with the

Butterfly approach to life and being truly alive. The work

since 1978 consciously exalts the wonders of life.

To Play, Childhood and

Family

In 1962, as I finished my

fourth year of teaching in Pennsylvania, I acquired

Picasso’s book of drawings called “Les Dejeuners”. It never

changed my drawing style (Matisse had long ago done that)

but it made me conscious of the need to play with form and

ideas. Picasso was an old man but in that framework lived a

child at heart. Now as I reach a similar time in life, I

give homage to this child! Picasso had taken Manet’s

“Luncheon On The Grass” and spent two years just playing

with one idea- from 1959 to late 1961. My work at times is a

commitment to play.

|