|

American

Supra: Book Three

Fulbright Scholar in Tbilisi and Other Cities

After September 11, 2001

It must be a peace without victory…Victory

would mean pace forced upon the loser, a victor’s terms

imposed upon the vanquished. It would be accepted in

humiliation, under duress, at an intolerable sacrifice, and

would leave a sting, a resentment, a bitter memory upon

which terms of peace would rest, not permanently, but only

as upon quicksand. Only a peace between equals can last.

Woodrow Wilson, 1856-1924, Address to the US Senate

But the artist appeals to that part of our being which is

not dependent on wisdom, to that in us which is a gift and

not an acquisition- and, therefore, more permanently

enduring. He speaks to our capacity for delight and wonder,

to the sense of mystery surrounding our lives; to our sense

of pity, and beauty, and pain.

Joseph Conrad, 1857-1924, from Youth, 1902

Nonviolence and truth (Satya) are inseparable and presuppose

one another. There is no god higher than truth.

Mohandasa Karamchand Mahatma Gandhi, 1869-1948, True

Patriotism: Some Sayings of Mahatma Gandhi (1939)

When I remember bygone days

I think how evening follows morn;

So many I loved were not yet dead,

So many I love were not yet born.

Ogden Nash, 1902-1971, from the Middle

Tbilisi 1: After September 11, 2001

An alert goes out to meet at the Sheridan Metechi Palace

Hotel on September 28th. It is a meeting of all

Americans. There is a system where wardens are chosen to get

out the word to all American citizens if there is a threat

of any kind. At this general meeting, attended by over 300,

we are informed that the Georgian police have discovered

that Embassy personnel have been followed with the purpose

of kidnapping. We are told, “At this time, we know of no

threat to non-Embassy people but a warning of increased

caution is in order.” One lady asks, “How can you tell if

you are being followed?” The answer is vague, since many

Georgians follow Americans to hear English and improve their

own skills in that language. Afterwards we journey with a

number of Americans and their friends to a restaurant that

has great pizza. With the alert still in our minds, it is

good to hear English spoken and sit in the midst of a group

where you think you knew their intent. Raphael, our driver,

picks us up when we call on our cell phone. No one can rely

calling on a regular phone. Raphael is a fine guitarist who

cannot find work in his field because of the economy. One

couple at the restaurant has an architect driving for them,

another a doctor, another a scientist, and so it goes.

Raphael is very good at his job. He drives us home and then

watches while we get into the apartment. He is part of our

protection against the threat for which we were alerted.

A few days later, we are invited to an Embassy dinner and

jazz session at the Ambassador home (at this time, no one

fills that post).

I learned yesterday that the reason that I got $500 for the

International Plenary of Artist in Kutaisi instead of the

$700 that was promised was that I was re-categorized at the

end of the session as a “graphic artist” instead of a

“painter”. It made no difference to them that I create

paintings. The criteria I now know is that graphic artists

work on paper and painters work on canvas. The old Soviet

system is still alive, well and functioning. It also makes

no difference that the canvases were awful to work upon and

the paper a little better but with perseverance one could

create a quality work of art. It also makes no difference

that I was never told of this distinction and outmoded

definition. I had stepped into the 19th century

with the Communists still in positions of power. What would

they have done with my friend Robert Wilson who does not

even do his own creations but hires skilled craftsmen to do

his work for him? Who is paid more in the space program at

NASA: the craftsman on the line or the artist/scientist who

dreams of the way to the stars? Sweat is not the criteria

for quality and value in the 20th and 21st

century. The concepts are not only out of date but truly

primitive. I will teach that the 20th century

recognizes works on paper as paintings, not a definition

rooted in the dim past without any present rationality to

justify it. Of course, I will teach at the Tbilisi State

Academy of Fine Arts which still classifies its professors

as “graphic artists” and “painters”, paying them accordingly

(paying each classification too little to live upon).

At one time in history, there was a need for the artist to

be the producer as well as the creator of the idea. Now, I

do not know of one architect who paints his ideas in the

design phase to present to a client or places one stone on

another when the construction phase starts. Title is not the

coin of the realm today; information is. But should I really

be surprised with this? The rules were constantly changed

all the time in Kutaisi. They functioned by the old Soviet

system. Wait and I will tell you what to think and do! There

was no concept of purpose or goal about the program. Artists

were not encouraged to exchange ideas but to work, to

complete the required five works of art. It was a program

for workers of the world…. I created over 40 paintings in

the 30 days (of which, they only received the five that was

ordained). As one artist from France said, “This is a

pattern etched into an antiquated past.” Maybe one thing

that this Fulbright Scholar can do in his time here in

Georgia is to help some young people step into the 21st

century.

In this century, idea is everything. Material is only the

skin for the idea. It is not without reason that “a work of

art” is called that, separating the “work” from the “art”.

At one time in history, work and skilled laborers was rare

(ending in the 18th century or earlier) therefore

the artist was the maker and material was tied to the

“idea”. This is no longer true. Anyone with an idea can hire

skilled craftsmen to execute “work” for the “art”. Wilson

has proved that over and over again. He created one idea in

theater while workers sculpt or paint another idea while

still others prepare the opera house for his scenes for a

classic opera. The future belongs to the idea man. All of

Europe, America and Asia has embraced this concept.

Information and creative thought is the future. I have been

reading F. L. Wright’s “The Future of Architecture” where he

separates the past from the present in terms of the

percentage of skilled laborers available. He says the

machine is the tool of the 20th century and

information is the currency of the 21st century

(using the computer). When he said that in the early years

of the 20th century, he was ahead of his times

but now the times have caught up.

What bothers me about the symposium for artists in Kutaisi

is that we were sent out into the mountains to paint

“scenes”, not exchange ideas. No time was planned for the

painters and graphic artists to exchange information from

different countries and different points of view. For an

artist, the idea is everything.

Part of the problem is that the Communists did not allow the

visual artists to think any new thoughts. Socialist Realism

was the party’s approved form of visual expression and

nothing else was allowed to exist. In the performing arts,

it was the same and yet the traditional performing arts were

allowed and encouraged to exist and excel. I am amazed at

the level of performance in dance, singing and playing

instruments but these arts are repeating old forms, old

compositions. You can learn your “craft” without having an

original idea, only small variations were allowed according

to personality. Seeing the teacher of Georgian dance with

his stick enforced my image of art education in Georgia. I

know; you learn. Me Tarzan, you student. I will be different

with the students, asking them to be partners in the process

of their own learning. Nato, the professor of English

literature at Kutaisi State University said after one of my

lectures, “It is interesting to see you teach. We are not

used to your methods. It is refreshing. There is no lack of

knowledge and information given the student but you make

learning fun. I will try a little of it. Georgian education

is not based on the joy of learning.”

Yesterday, I met a Georgian architect Temur Jordaze who

wanted to know more about architectural lighting. I told him

the little I know and directed him to architects in the

States, particularly the firm of OlsonSundberg in Seattle

who have their own daylight lab which can create the daytime

lighting for any spot on earth. I learned later that he

followed my introduction and journeyed to Seattle. I may

have started something. He may just bring back to Georgia

new ideas in daylight lighting technology to create future

buildings. Information is still the way to the future. When

I ask him, as he is a professor at Tbilisi State Academy of

Fine Arts as I am, “When my classes in the second semester

start?”, he told me, “About February 1st or March

15th.” He said it with a straight face and it was

all that I could do not to laugh. Yet, I learned later that

it was a ridiculous statement and absolutely correct. At

that time, I thanked him and though, “OK, all I need to

teach is a place, students and a time. If the Academy makes

its schedule of opening second semester on the temperature

of winter and has no electricity and therefore no heat, I

will move to a place that has heat and space.” The Academy

did not start classes until March 1st and

therefore I taught all of February at the National State

University, letting my Academy students know where I was

lecturing and allowing them to come. Each class had over

seventy students.

I taught my class on museum studies at the Academy today. We

circle the desks which appeared to have never been moved

from their authoritarian positions facing the front of the

classroom. We build a board of trustees, make policies,

recruit new board members and do other American Museum

Association ideas. What is for me a way of life is all new

to them. The Director of the Art History Department, who was

sitting in, asked, “Do museums that are supported by the

government have this kind of system?” My answer was, “Yes.”

“Do art galleries?” “No,” I said, “businesses do not have to

have American Association of Museum’s standards or

accreditation.” “What is accreditation?” It was at this

point that I knew that some complex ideas had to been

explained after finding any close equivalent in Georgian

life. Our ideas are tied so strongly into American freedom,

democracy and individual rights that it is hard to explain

them here. All decisions for years have come from the top

down, not with the people on the bottom up. The daughter of

a good Georgian friend went to have minor operation. She has

lived in America for her high school years. Now, she is

annoyed that the doctors would not tell her what they were

doing. She told them it was her body. One doctor said, “For

now, it is ours.”

My techniques of teaching have been perfected over the years

by taking time off to learn how to get across material in

short segment (by becoming a disc jockey for a time) and how

to use my voice as an instrument of learning (acting in

plays to learn projection). I use the whole space of the

classroom, an idea that is revolutionary here. I break the

imaginary plane between teacher and student all the time.

For me, using the space that normally causes a separation

between the teacher and the student is a way to identify

with the student and his or her needs. The Georgian system

is to stay in front and tell the students information (which

is out of date by the time they get out of school). Their

job is to memorize, not think. I make them work at thinking

and, eventually, they enjoy learning. Also I use humor to

get across major points. An individual who can laugh is open

to new ideas. I enjoy teaching and these students are so

appreciative.

In any situation that an artist finds himself, he must

look at different ways to see information. A simple question

like “Do you have the keys?” may be the beginning for a new

way of thinking about the events of daily life anywhere.

To Have or Have Not

It all started innocently enough. My wife Anne and I were

leaving our apartment in Tbilisi and she said, “Do you have

the keys?” I was in one of those moods where a simple answer

just is not in my nature and I said, “No, the keys have me.”

That did it. Much of that day, the next and into the week

all that I could think about was all the things in daily

life that “had” me in their grasp. I thought of all that had

gone on since leaving America to come to Georgia as a

Fulbright Scholar.

At one time I did not have a computer to type out my

articles. I had a typewriter who had me. Before that I wrote

out my thoughts longhand (which I do again now when there is

no electricity which is often) and then passed them over to

my secretary who had me until she was finished. Now, it is

email. I check it the morning, the afternoon, the evening

after dinner and, if I get up in the middle of the night, I

check in to my master again. It has me good. Writing letters

seems like something that is in the past. Even then I had to

have a certain pencil or pen. Of course, I do write at times

and then fax the pages to the some unseen source. The fax

has me too.

It is not enough that my computer, fax and email have me.

Now I need a scanner. Of course, without all this, I have

(or it has me) my office away from my home office, the

American Embassy of Georgia. They know me by name. They have

me because they own my time and knowledge when I pass over

some gem that just must be done “now”. Time has me too.

Raphael, my driver in Tbilisi, has me. When his car is in

the repair shop, they have me. The apartment owns me more

than I own the apartment. In America, just ask the bank who

holds the mortgage on our home, having sway over a cut of

the social security check that I now get from the government

since I retired to be free from others “having my time”. The

income tax deadline will pass while we are in Georgia.

Anyone who does not believe that the government does not

“have” us is cheating on their tax returns. Even at this

distance, my dog and cat own me. I get daily reports of my

relatives taking them out when they want to go. Little

things have me too in this modern world. A lock when it will

not open. The bureau door that is jammed and I cannot summon

its services. Electricians and plumbers have me. CNN news on

my laptop controls my first hour of being awake.

In America, it is the telephone. Now don’t start me about

the telephone. Even when I am not there, the answering

machine has a message that I just can’t miss. Those unwanted

calls in the evening that starts with, “Joe, it is wonderful

catching you at home. We have a deal that you just can’t

refuse.” Well, “brother (actually “bother”), you don’t have

me!” I can hang up the phone now as fast as any Western

gunslinger. (In fact, one of the joys of being away in a

foreign land is that you don’t get programmed calls

anymore). In America or when I go the Embassy in Georgia,

the television is something when it is on “has” me. When my

mind is tired, I watch anything, falling asleep to the soft

sounds of murder, love, Chinese news broadcasts (in

Chinese), sports of any kind, commercials, talk shows, “sit

coms”, and cartoons. All of them “have” me for a time. And

then there is the addiction to the Internet! My bed has me a

third of my life. The bathroom has its time too. The craze

for health has me. At least my wife and I do not have each

other. We share each other.

“Who has me now?” I ask some days. Who owns me for this

precious second or minute? The car, the computer, a promise

makes “To have or have not” the question of the day. Some

times during the day, a simple question like “Do you have

the keys to the apartment?” is more complex when you begin

to think about who has what and when. Do I have a name or

does my name own me? It is a puzzlement. Have you ever

answered questions to an insurance form where they want your

medical card number and the company, your social security

number, your telephone number and your address before they

ever try to learn who you are or why you want to see the

doctor? I have learned the secret though. It is to “unhave”.

For years, I collected works of art until I began to realize

some of them “own“ me. To unhave frees us all. In Tbilisi,

Georgia, I have less things and more time to find out who I

am.

Another element that artist needs is more time, therefore

processes that extend the psychological moment is critical

to exploring the wonders and mysteries of everyday living.

Extend the Moment. Live Longer.

Driving down Rusteveli Avenue early in the

morning, before going to class at the Academy, watching the

cars that pass in no seeming order, thoughts raced around

the speedway of my mind. There is so much to do and so

little time to do it all. And “all” is what most of us want

to do each day. We forget to leave a little for the next

day. We have forgotten Hewingway’s lesson when he left a

story incomplete in a day’s writing so that the next day he

had someplace to start the process of creating a new day’s

work.

Now on this street in a strange land, Georgia, I

determined that I would see, record and marvel at this

special sight. There had been so many days when that same

resolution had been made and I was surprised when I realized

that I had missed the whole wondrous scene, thinking about a

telephone call which had to be made, or a lesson to be

planned, or a chore that just had to be completed in the

next fraction of a second. This time I was determined that I

would see and enjoy.

Going down a hill, I received glimpses of the

smooth waters of the winding dark river through the trees.

Then the scene opened as I got closer. Finally, it spread

before me: a simple scene of blue sky, glass-like river

water that so many have struggled to control, the

August-filled trees and bushes, and another hill to climb in

this Russian-made chariot. The moment is held as long as it

can be held. It is extended in time by the joy of the scene

with Georgian churches perched on the edge of the hills..

The serene horizontal of the far bank, the water that dances

with light and soft color fills my being. I have done it. I

have captured the moment. The fast pace of modern living has

not won the day. Light, color, water, sky, green-green and

rocks are all that exist.

It is the same struggle that was depicted in a

recent movie, “Star Trek: Insurrection”, which we saw and

enjoyed in Russian. A major theme centered on a battle

against those who would cast out innocence, art and

fulfilled-living and those who held these attributes close

to the heart. The 300-year-old beauty showed Captain Pecard

how to extend the moment by blowing pollen from a flower.

The star-like golden specks gleaned in the sun’s light in

slow movement. Pecard, a man of the future (our future of

technology and swift action) was forced to slow his glaze to

a shuffled pace.

The river is before me again. I have to rush to

the American Embassy to get something reproduced quickly.

That is what Embassy does. It helps Fulbright Scholars. It

is not Kinkos, which was created to speed up our office

work, but they are a help in Georgia.. Again, it is a

struggle to forget my hectic job for a moment. I have to

say, “Work does not exist. Work does not exist.” And for the

moment coming over the crest of another hill, diving into

the green blue of the river and the park lined with men

waiting for work, and the magnificent Tbilisi sky, work

disappears. Isn’t that what all of us wish to do? To live

longer! Not in years, but in the extension of the moment. It

is not the length of our lives that counts but how we use

each precious moment and extend those moments. Tbilisi,

Georgia is a wonderful place for extended moments. Modern

life does not allow long periods of slow contemplation, but

when we can have them they are the joy of living. We can

truly see, hear, feel, enjoy and learn.

It reminds me of the story of the beggar in an

India market. He is starving. All day, day after day, he

begs for money. A kindly merchant watches this drama for a

week. Finally, he gives the beggar money and tells him to

buy himself some food so that his life would be prolonged.

The beggar thanks the merchant and takes half the money and

boys food. With the other half, he buys a flower. The

merchant is angry. He has not given the man money to throw

away.

“Why have you bought that flower?” asks the irate merchant.

The humble beggar answers, “Half your money will

keep me alive for half a day. Holding the flower in my hand

while I eat makes life worth living”.

Tbilisi, Georgia, on this special day, is this

beggar’s flower.

Tbilisi, Georgia 2

I sit in the twenty foot by fifteen foot living room,

looking up to the extra high ceilings and a crystal

chandelier. The doors are four inches thick and hold out the

sound between the labyrinths of rooms. There are wood inlaid

floors, a refrigerator from the 1920s which hold the

Georgian beer which I love so much, a washing machine is

rattling its age from the 18th century (it seems)

and books, books, books, antiques, antiques, antiques,

dating back to the Ice Age. Everything is lovely but it is

antique. I took down all the dark paintings, in style as

well as color, and put up my own paintings. All my color

seems strangely out of place. As I have said before, black

is the dominant color in Georgia. Well, that’s us, strangely

out of place and time.

I called my daughter, Samantha, today and told her, “I love

you,” before she had a chance to speak. She laughed, because

she says that I am weird, and said, “I love you too, Dad.”

Funny but I needed that feeling from home. Being away as a

Fulbright Scholar, you don’t need material things (you can’t

get them anyway) but you do need to know that some few

special people love you as you love them. The Georgians are

right in the supra. Family should be toasted at every meal

because it is the life blood of this society, or any

society.

What I saw in Kutaisi, in Kharaguali, at the Black Sea, here

in Tbilisi, at Rustavi, and later at Telavi when we went to

a dinner and had a supra was the possible death of the

supra. It was created for two reasons: to celebrate the most

important things in Georgian life and to keep the creative

minds of the participants alive as their bodies were

oppressed by outside forces. What is happening is an

internal stagnation of the tradition. It should have some

codification at the beginning and the end. The beginning of

the supra should be honoring guest, country and family, the

three staples of Georgian tradition; the end should be to

honor the tamada, since this is a demanding and taxing job,

but the middle should be free to celebrate ideas, to build

upon themes, to let the creative minds of the participants

fly and soar. That is how it began. That is how it should

grow. That is how it will survive as a vibrant part of an

emerging democracy. It should be a time to celebrate the

poetry of ideas and feelings. It should live and grow.

Things which do not do grow, die!

We have been emailing friends, being starved for news

because there is not much and rumor fills what there is. For

a while after the alert, we were feeling the tension of

threats from local terrorists but our routine is now built

around safety.

A few nights ago, we stepped into it again, a rare night of

wonder and beauty. We buy our tickets and are told that this

time it is a ballet. For a change, it is, sort of, and a

pageant, sort of, and the presentation of a dance, music

school, sort of. What it was “was wonderful”! The age of the

performers was between seven and twenty, all professional in

their parts, all two hundred and fifty of them on stage,

sometimes at the same time. How can a society so

knowledgeable in the performing arts be so backward in the

visual arts? This was the Batumi Children’s Concert.

“Children” only in name and age. In performance, they were

as good as it gets.

I went to teach my class in 20th century

criticism with Ketevan Kintsurashvili but it was delayed

because the students were out in mass painting a group

action mural and listening to a hired rock band. Anne stayed

behind with Nino, another professor in the Art History

Department, to watch how Georgians make their delicious

bread. She is fascinated. There is a large ceramic drum-like

kiln on a dirt floor. It is heated to blazing hot, then the

dough is slapped on the side and the bread is baked. It is

then scrapped off like our pizza except it is horizontal. It

is again, using that overused word, wonderful!

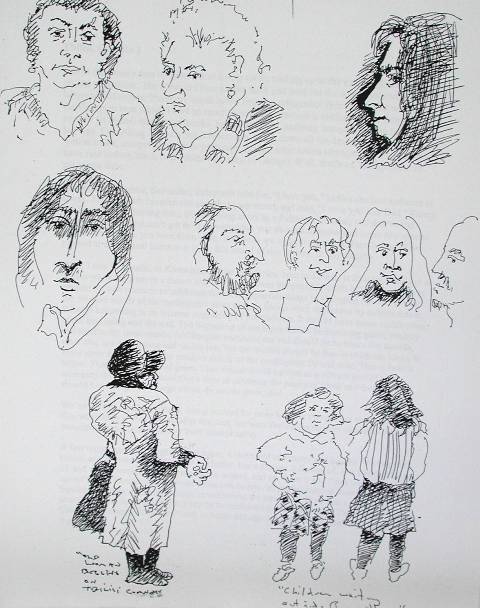

Outside the Opera House, I draw and observe. Only the young

wear color and that is just for accent to the black or red.

Tight pants and shawls are everywhere, and one little girl

is all in purple which stands out against the blacks, grays

and browns. Rustelili Avenue is the main six lane street

through Tbilisi and is always busy. You do not cross because

everyone drives too fast and never stops for anything,

especially red lights. So you go under the streets, passing

the beggars, small shops and strolling musicians. In the

Opera House, a man comes in front of the curtain and tells

the children the story of “Swan Lake”. I cannot understand a

word he says but the tone is storytelling and the way the

children listen I know that it is a story.

Swan Lake is a full adult ballet, danced by professionals to

a full symphony orchestra. It is not a children’s

performance although the house is packed with mothers,

fathers and children. It is a noon Sunday performance. The

dancers move with extreme talent. The children can come free

if they sit on a parent’s lap (normally the mother’s) and

all this for 10 lari ($5.00 USD).

The Opera House is decorated in the old, grand style with

exquisite sets, a large stage, magnificent chandelier and

side lamps in the antique fashion of the late 19th

century. The house lights dim, the second act begins where

the first act ended with the young hunter who has fallen in

love with the graceful swan. Twenty four other swan

ballerinas dance as one. The black swan/wizard makes his

ominous appearance. Later, under the spell of this black

wizard, the white swan turns black. They dance together. The

young man gives his heart (flowers) to the prima ballerina

(the black swan now) and she spurns him, leaving with the

magical male black swan (now a dark human figure) and the

second act ends at court with the heartbroken young prince.

In the last act, the dark sorcerer and the young man fight

to the death. The young man wins. He and the white swan are

joined forever and ride into the heavens on a chariot.

Curtain! Marvelous, even with a story that is an excuse for

great dancing. Flowers, which are in abundance on every

corner of Tbilisi for a reasonable expense, are presented

from the audience to the prima ballerina, the lead male

dancer, and some selected other ballerinas.

That night, I work on a new series of paintings called

“Quarter Turn”. The idea happens as I look again at Monet’s

Haystack series. All the compositions are the same. Only the

light and color changes. I ask myself, “What would happen if

I painted the same composition and made a quarter turn of

the color study so that the order of the colors would change

in terms of the spaces they inhabit?” What happens to my

pleasure and surprise is that the paintings change in

character although the composition stays the same and the

colors are the same but in a new order. Ideas have a life

cycle like people and organizations: birth, life and death.

This idea is in its infancy

I decided to go to the Academy and draw with the students.

They have a model and I need the practice. What I did not

know until later was this is again revolutionary. Teachers

do not work alongside students. One young girl meets me and

shows me where I am to work. It is a studio in the 19th

century style (I am saying that often but it is true). It is

a large room with a skylight, dirty floors (I will never

bring my jacket or red bag again), high Gothic arched

ceilings. For the painters in the class, their palettes are

arranged in a Renaissance style from white to yellow to red

to…etc. until black. The painting is also locked into the

last century. The drawing is Renaissance. Well done, but it

is Renaissance and classical (not a bad tradition if the

students are also allowed to do 20th century

ideas). It is interesting to see how the students react to

my drawing style. I call it “cluster thinking”. They have

been taught to build the figure from proportions and basic

forms. For me, all this is in my head and not on the page. I

try to find the clusters that make up the heart of the

experience of seeing. It is how the human body begins as a

cluster of lines and forms. All else can be drawn around the

key cluster to the vision. You have to have Renaissance

proportions but it is internal and not on the page. You know

this before you look for the prime cluster.

As I began to draw, I noticed that nothing at the Academy

starts when the schedule (if there is such a thing in

Georgia) states. I know that I have plenty of time to draw

and write before even seeing the professor for the class. As

I came in I noticed professors standing around outside,

smoking and talking until 10:30 when a class was to begin at

9:30.

It is understandable. No one is paid much for their efforts.

A professor makes between 15 and 20 lari a month, no salary

to live on, no salary to rush to class to teach. The

professor’s attitude is passed on down to the students. Only

a few come to class on time except me. I am stupid enough to

think that art is its own reward.

In front of me is a model stand, an old mattress, torn

clothe, a kind of shawl for an added touch of color with a

piece of silk. I hope that today’s model is young. Yesterday

the models were ancient and huge. The model comes in, a

young lady in late twenties, and she puts a clean sheet

which she has brought over the model stand. I think, “I

wonder how much it would take to scrub these floors. I guess

scrubbing is out of the economic question”. It is cold and

the model plugs in her electric heater, after she repairs

the plug. Nothing is simple here. My heart goes out to this

model who poses in her panties and for Georgia.

Mzia came to clean today and help Anne with her Georgian

phrases. They have struck up a good friendship. Later, the

landlady came with the men to install a gas heater which

will vent to the outside. They drill through one of the back

walls. As they finish, we are told that it will warm the

whole apartment It barely heats the one small room where it

is placed and we close off two rooms to the cold to take the

chill off the rest of area. We will use electric heaters in

the rooms where we spend the most time, the bedroom and the

computer room, and we will survive the winter in better

shape than most Georgians. We also keep a kerosene heater as

backup for those days when there is no gas or electricity.

Tonight we attend the performance of Jesus Christ Superstar

by a visiting Russian company. We know it so well that we

are looking forward to hearing it in Russian. In fact, we

saw Jurasic Park 3 in Russian. How much translation does

screaming take? Again, we were surprised when the company

did the whole performance in English. So far, nothing that

we have attended is what we thought it might be but the

quality of performance is there. They did the whole musical,

two standing encores and then came back and did seven more

encores as a tribute to the history of rock and roll. People

were standing in the aisles, on the side of the theater, and

all those plus the seated audience stood as one and cheered.

It was that good. We have seen some magnificent performances

on Broadway but this production rates with the best. These

performers could hold their own and make a living from their

profession anywhere.

My pattern of getting up in the middle of the night and

staying up painting will have to change. I need to stay in

bed and try to get back to sleep but it is hard. My mind

keeps racing to all the projects that I am juggling:

painting, classes, exhibitions, fund raising, consulting,

etc. I cannot complain how it has affected my painting. I am

doing the best work of my life. Why it is that getting away

from America brings out the best in me? Maybe it is

perspective. I get to look objectively at my ideas, my work

and my life. Whatever it is, the painting is as good as I

can be at this point in time, pushing seventy from the lower

end.

I have begun to think that “Quarter Turn” is not just a

physical thing for the painting, an idea or an action, but

it is more like the changing of seasons. Winter, spring,

summer and fall are a quarter turn therefore I will instruct

the American Embassy to make a turn of my painting every

three months. This idea of seasons changing the colors again

goes back to the Impressionists. I have been thinking a

great deal about Monet and his experiments with color and

light. I do not wish to do Impressionism but there is a germ

of an idea working at the corners of my mind that has real

meaning and merit. It is beginning to emerge that may cause

a whole new direction in my work. It is always a troubling

time when I lose sleep but also it keeps me young inside and

is exciting.

Tbilisi 3

Our record is still in place. We still have not gone to one

performance where it happens as the program reads or was

something other than what we were told.

I have a good session with the gallery directors. It is an

open discussion of hopes, visions, and concerns for their

businesses. We discuss the state of the visual arts in

Georgia. The only negative that I get back is, “Yes, you can

do that in America but this is Georgia. We cannot find money

to do what is needed.” I agree that I do not know Georgia

yet as the people in that room do therefore they have to

come up with long term answers to their questions. My

question to them is, “If you try something new, could you be

any worse than you are now?” I know that two of the

directors who did not speak up have gotten grants and did

some new things in Georgia. After class I ask them to report

on their projects the next session. Until then, I promise to

visit all the establishment of those present and discuss

their problems on their home territory. We will all meet

again in a month and begin to collectively discuss

solutions. While we are engrossed in this discussion,

protesters march on Parliament and Rustevili Avenue is

closed to traffic. Also they lock the doors of the museum

where we are having our meeting. Thousands are marching. It

is the sixties in the States for me all over again. When the

session is over, we are lead by a museum guard through the

labyrinth of passageways under the museum and out a side

door.

The next day the protesters are still marching and

assembling in front of Parliament. This will continue until

Parliament breaks up its talks this weekend. I call the

Embassy to see if I have class at the Academy on art

criticism and am told it was safe. The marchers are

peaceful. But I remember Chicago’s marches and what started

as peaceful demonstrations became violent. If you are

assembling a large mound of hay, all it takes is one match

to set it aflame. We cancel my class and our plans to go out

to dinner in that area.

One thing is sure in my mind after working with the museum

professionals and the owners of art galleries: arts

management and knowledge about American art are dramatically

needed in Georgia.

Tonight, in what the Georgians call “old town”, we attend

two art openings in the same building, Caravan-sarai Gallery

in the National Historical Museum. By far, the exhibition by

Georgi Alexi-Meskhishvili is the strongest contemporary art

that I have seen. He is now teaching at my alma mater,

Dartmouth College, but for years he was the senior set

designer for the Opera House and the National Theater. What

shows so strongly is his sense of play with images, words

and surface. Another art exhibition, by an artist named

Levon, shows art work from the 1980s that had been banned by

the Communists. It also is strong in content and execution.

Caravan-sarai is a wonderful space on the second floor to

show art. I will look into having it for my December

exhibition.

I sit now away from the crowd, feeling the effects of two

days with a cold. I am ready for a few days of rest. We will

go home early tonight but I am also glad I came because the

art is stimulating. It is as good as anything I have found,

powerful and playful at the same time. It is refreshing to

see this quality of work in contemporary art but it is also

too bad that the best Georgian artists have to go abroad to

find a market for their creativity.

We shop at our local market and now we are “regulars”. Again

I need rest. This cold has me extra tired therefore I nap

for an hour. When I awake there is no electricity. This is

the first time for us in Tbilsi (in Kutaisi it was a daily

outage). Our driver, Raphael, has gone three days without

lights and heat and his son, Michael, could not study his

lessons in Russian, English and Georgian. It gets old very

fast to be without electricity all the time. People have

learned to put up with it for years. I can understand the

demonstrations now by the students and their march on

Parliament. Candle light is romantic only when it is a

choice.

I talk to Anne about how, with all this painting everyday, I

am back to the place in my life where I wake at night,

visualize a whole or part section of a painting, and paint

it in my mind, the colors materializing as I put them in

place. There is a study of a woman who has been tested to

hold 10,000 bits of visual information in her mind and can

recall any segment. I can walk through a gallery quickly,

almost running by the paintings, and later tell you all

about the colors, lines, brushstrokes, forms and content of

the works. It takes me about two walk-throughs to collect

this visual information. Sometimes years later I can walk

again through that same exhibit in my mind’s eye and tell

you where each painting was placed and how it was painted. I

have never thought much about this ability because it has

always been a part of my sight but now I understand that it

is a gift. School never rewarded visualization except in art

so I learned to play the word games for success but my

strength has been my visualization. Just as I said the word,

“visualization”, to Anne, the lights came on and we get up.

I help the American Embassy interview five women for a

Hubert Humphrey Fellowship, 30 minutes each. Two are very

strong, one came close but did not have the advance degree

needed to go with her stated purpose for applying, and two

are too young to really qualify. We will send one of their

names to Washington for the final decision. I am impressed

with the strength of all their resolve that Georgia will

change for the better if they have any say in the process.

No men apply.

We go to the Free Theater, which is not free in admissions

cost, to see Medea. A haunting classic beauty sat in front

of us. There can be no place on the face of the earth with

as many beautiful women in the Greek statue classical sense.

The men are good looking but many of the women are

spectacular. At every event, I marvel at their features.

Matisse and Picasso would have models forever from this

Georgian society. I know that I have remarked on this fact

before but it still surprises me walking in the street or

going to a theater performance.

From the womb of the Gods (the eye of an ancient sculpture)

comes Medea with a dancer of the fates interweaving her

fatal despair in a kind of dance macabre after she murders

her children (who came from her womb). The many faces

(masks) of our lives are worn by the actors, just as the

three fates (the cruel masked sisters who spin our destiny

and cut the thread of our lives). The four masks are worn

first by the fates, then Medea, then the dancers, then put

away. The dancer of destiny and Medea look into a momentary

tableau. An aged masked figure appears, carried by the youth

of the gods. His mask is forged in the fires of Vulcan and

Medea becomes the temptress, the shaper of death and a

faithful, adoring lover.

The old man takes off his mask and finds his love, Medea.

All that is left for Medea is the favors of sex (which when

kissing stings her lips). The old man leaves, receiving the

favor of a kiss, carried by youth to die. Then the youths

come again, exchanging symbols of Medea’s crime against her

children and begin to rebuild the image of the Greek gods.

Her husband returns from the wars and finds out her bloody

deed. They live together in an embrace of peace in a sea of

madness and the broken pieces of the god’s image.

After her husband leaves again, all that is left is a mask

existence for Medea. Her mother returns from the grave to

torment her with the punishment of Zeus. The dancer of

destiny returns with the four masks. After removing the last

mask, we see a fifth painted on the dancer’s face. She

dances with Medea and all the pieces of the broken god are

assembled. Medea’s time is up. The fabric of her life is

broken like the statue and she dies under the rubble of the

god’s statue crumbling upon her.

The lead woman who plays Medea is magnificent, a strong

character for a strong part. Flowers are thrown on the stage

as she takes her last bow, flowers are handed to her by the

audience, flowers are everywhere. For us, it is another

simple evening in Tbilisi, Georgia.

I have found what I sought, a tool to teach arts management

to students and professionals. It has been in front of me

all the time, the supra. The tamada is the CEO or director,

the others are players. Today I use the supra for them to

begin to think of “how to find grant funds”. The idea of

sweat labor to balance a request for funds from a foundation

is totally foreign to the student’s thinking. The Communists

and their parents gave but never asked what was needed. To

analyze strengths and weaknesses and then to pursue only the

strength is again a new concept. Getting money through the

grant process is second nature to me. I do not need to think

about it. I just do it. I start with what is needed, work up

the budget and then proceed to the narrative. Teaching these

concepts is so hard because asking for funds is new and I

work through an interpreter. The supra, at least, is

something they know. What they are not used to is taking one

system from one source and using it in another context.

After class, I stop down in the pits of the Academy to see

my carpenter. He is finishing the sanding of the framework

for my painting that I sold to the American Embassy. He is

proud of his job and I compliment him with a thumps-up sign.

Today is the day when I move the paper painting onto the

framework. It is exciting to think that finally the time has

come but also a little frightening, two months work which

can be lost if the glue is not right, the workers cannot

communicate or my planning is flawed. I have gone over the

process in my mind again and again. I know the first step,

the next and the final finishing with the hot iron to smooth

the surface and make the glue permanent as a bond. I am

working with help who do not understand my language or this

concept of art. I work with glue that comes from Turkey

which I never used before this time. I did do a small

example on a board but this is a six foot by six foot

painting on paper. I have a momentary panic attack when a

thought comes into my mind, “What if he flipped the template

and the shaped painting does not fit?” No, I cannot think

defeat. This can be glorious or it can be like many creative

attempts in Georgia, a bust. If I fail today, I have a

backup plan to use the framework for a new painting. I will

not fail today.

We struggled but it is finished and it looks great. The

American Embassy will be pleased because I am pleased (and I

am a harder critic of my work than any patron). Even my

co-workers admired it. Anne thinks that my painting now is

my best (and she has learned to be a harsh critic). Tomorrow

we will take it on top of Raphael’s car to the American

Embassy of Georgia for its final placement on the wall over

the fireplace in the master ballroom.

I cannot think about that now. Tomorrow I have three

lectures, two in Rustavi, a town near Tbilisi, and one at

the Tbilisi State Academy of Fine Arts, my host institution.

Today, I gave the “American Education” lecture to the

National State University, stressing the three kinds of

democracy which is the basis of American education: 1)

Thomas Jefferson’s idea of educating the best and the

brightest to lead the nation, 2) a mercantile America where

the government gets funds to aid the people, and 3) Thomas

Paine’s idea of one vote, one person, so that the people can

change leaders who do no serve them well. We play my

information game. The students enjoy it because it brings

home how much they “need information”. I discuss the four

aspects of American education from a leadership perspective.

If the audience knows nothing, tell them. If an audience

knows a little, show them. If an audience knows as much as

you, work alongside of them as a partner in education. If

an audience knows more than you, get out of their way but

find them the resources to accomplish their goals.

The one thing that is troubling now, living abroad, is

the rise in international terrorism. Everyday is a challenge

for security and well being. This new threat to freedom adds

an additional burden to any Fulbright Scholar. This article

tried to examine this situation.

Living Abroad

in Today’s World

You wake in the morning at six in an apartment in Tbilisi,

Georgia. In your mind, you go over what the day will hold

and what it will not. Before September 11th in

America, it held endless possibilities- walking through the

bizarre to view all the merchandise from around the world,

stopping by the river to view the paintings and objects from

now-open attics, strolling along Rustaveli Avenue (the main

road going through this city of 1.6 million people),

stopping at the US Embassy to check on the week’s schedule,

or just going downstairs to buy bread, cheese, some Coke,

Russian potato salad and bottled water. Now, since the

tragedy, I wake and take things off the list.

If we go to the bizarre with its constant stream of milling,

jostling people, looking for the just the right thing or

some stable that is needed for the day, we take our driver

for communication and protection. We do not stop by the

river to brose the venders’ wares. The bazaar at the river

has been a place where northern Georgian terrorists have

been sighted. Walking the main street in Tbilisi is a

decision that is made with “when” not “if”. We never go

there now in the evening, except when we have tickets for a

performance and our driver, Raphael, takes us and picks us

up directly after the event. Spar of the moment dinners at

some newly-found restaurant, on some street off the beaten

path, is out of the question, except after we check it out

during the day and plan the time and the departure.

Each time we stop at the US Embassy, new construction is

going on. Now it is large concrete barriers to replace and

partner with the already large concrete barriers to stop

cars ramming through and attacking this special place for

Americans. Just after the September 11th

declaration of war, all Americans were gathered and told

that they had been “possibly” singled out in Tbilisi for

kidnapping (therefore take “extra precautions”). We were

told to watch if anyone was following us. “Do not take

public transportation if possible. And when driving, leave

enough room between you and the car in front of you if you

stop”. That is so you can escape. One American asked, “How

can you tell if a suspicious character is following you in a

country where almost no American speaks the language,

everyone can look “suspicious” and people follow you all the

time “just to hear English” and “practice their language

skills”? Nothing has happened, although some of the Embassy

staff had been told by the local authorities that they had

been targeted for kidnapping, but the threat of something

happening makes you look over your shoulder when walking the

streets.

Our apartment on the second floor has two steel doors, with

a heavy forged slide lock on the inside door, and bars on

the windows (left over from Communist times). To get to our

door, we walk up two flights of dark stairs. In the evening,

when we go down to buy groceries at our friendly markets and

return home, the first action when entering the building is

to look behind the entrance door to a dark corner where no

one is hiding but the idea has been planted. One advantage

in any city, even when the times are not as tense, is that

you are finally known by your neighbors, your shop workers,

our man selling fruits and vegetables, and the other tenants

to the apartment house. The people around you begin to look

after your well being. You begin to smile at others who also

look over their shoulder because this has been a way of life

for Georgians for a much longer time than Americans living

abroad have experienced it. You find that how they react

conditions your actions.

I was teaching at a state museum to gallery owners and

non-governmental agencies when the great October march on

the Parliament Building came. The museum was closed with us

in it. Most Georgians stayed away from the marchers and

that area (most of my students did not), but after the

second day it became normal to adjust to “no government”

(since members of the Parliament resigned after the

protests). One of my friends in the States asked by email,

“What is it like living abroad now?” I wrote back, “Tense

but normal (and not tense all the time).” The one thing that

is comforting is the knowledge that these are the warmest,

friendliest, most hospitable people in the world. Situations

are situations. There is never a totally safe time in the

modern world. You make decisions based upon your priorities.

One of our priorities is the refusal to live in fear. Tense,

yes, but normal.

What keeps the mind and spirit alive and well many days

is ideas and images. The Greeks called that combination an

“ideate”. In Georgia, you need all the ideates that you can

create. The Rolling Around Effect examined this phenomena.

The Rolling Around Effect

Did you ever have an idea roll around in your head, bouncing

off the electric connections so that new connections are

created? It happens to me all the time. I get interested in

circles when flying over Arizona on my way to losing my

money in Vegas. The circles are new watering patterns made

by farmers to irrigate their land. The new patterns grace

the landscape as far as the eye can see. Next, the idea of

bubble technology is introduced to my brain computer by

Lucent Technologies where information can be stored and

transmitted by bubbles (just more circles). Next, I am

watching television and listening to the search for answers

for Alzheimer patients, thinking about the circles of

friends and stored information, emotions, memories of

earlier times that makes old age a vintage time in one’s

life. Last, I write almost everyday on this computer,

backing up the information that I create with marked discs

so that I retrieve the data.

Now comes the rolling around effect, the stew that is

produced when all these ideas are kept in the air like

bubbles. I know that the human brain is the most complex

computer in the world. I know that I keep notebooks and

sketchbooks and computer discs to keep ideas afloat for

years which might come together later as a “new idea.”

Now came the great “what if”! What if the computer industry

could put our thoughts on disk, not to place it back in the

computer but to place it back in our brain when we lose

information. I am naive enough to not know the damage that

is done when Alzheimer’s Disease strikes and erases the

computer of our mind. But also, I have watched a Computer

Doctor find 1070 viruses on my computer, clean it out and

reprogram much of the data that was stored, while also

putting up “walls” against a new attack from new viruses or

the reintroduction of old ones. I also now know that “Love”

can be a virus.

What if in the 21st century we put things together different

sources to create new solutions to old problems. We take an

idea of bubbles making the structure of information for our

minds, a dash of extremely advanced computer knowledge, the

idea of information storage for later use, and compassion

for those who lose information in older life. Simply put, we

download data when we are at the height of our information

capacity and feed it back into our brain computer later.

There are questions that come to mind as I dream this

solution. Are we the sum total of our memories or are

memories just the information to interface so that new ideas

are born? If we download the information in our minds at one

point in time, are we lessening the individuality of the

person over a whole lifetime?

What about the soul of a person? Is it the sum of the

memories or something which comes from outside the

information base of our collected memories? When we download

the memories to feed back later, are we damaging the essence

of the soul? The mechanics of the brain with its bubble (or

some other system) technology must have spirit as well as

material substance (memories). How do we insure that the

spirit is retained on our disc of information?

How will all this change education? We cannot separate

information into categories if it is all bouncing bubbles in

a matrix. Will we continue to hear a bell ring in our heads

from our outdated school experience (even if we attended a

school which did not use a bell) to separate math, reading,

art, music, physical education, science, politics, sex,

play, etc.?

Education does not stop in the classroom. We fly over

farmland, watch television, play with grandchildren, kiss a

loved one, and gather memories. I would welcome a backup

system for my life experiences. Maybe in the 21st century we

will be able to download, store and retrieve our minds.

Maybe Alzheimer’s Disease is a complex or simple

human-computer problem. I hope that I am behind the times

and others have thought of this already that have the time

and knowledge for a solution!

Tbilisi 4

I go to my normal class to teach with Ketevan

Kintsurashvili, my co-teacher in art criticism at the

Academy. Nino, another professor in the department, says

that she would like to participate lecturing when we discuss

Brancusi. I have prepared about half an hour of discussion

on how this Rumanian transformed Paris and the art world

with his seemingly simple forms. I have reviewed two work

that are at the Hirshhorn Scupture Garden in Washington, DC.

I though that this would be an easy day for a change since I

am not center stage. I am sharing our eight students with

two other professors. When I walk up the grand staircase

with the two plaster Greek statues on the first landing, I

am met by one of the eight who say that we were in the great

hall, where all the historical paintings hang like reminders

that this Academy is eighty years old and has never grown

up. I use the great hall on Saturday because of the size of

my architecture class. When the crowd starts to come in, I

know this would be no normal class. That day, I lecture on

Brancusi, his influence on 20th century art, his

ideas in sculpture with two examples from the Hirschhorn

Museum, to over 350 in attendance, including the Rumanian

Ambassador and his entourage. The event is sponsored by the

Academy and the Rumanian Embassy. I am prepared to speak all

the time in Georgia because you just never know. I had seen

the poster announcing this event but it was all in Georgian

and I did not recognize my name as a major speaker. In

brief, I wing it with my ability to talk and draw. It must

have been successful because Anne and I are invited to a

limited dinner given by the Ambassador and the Rector, where

Ketevan, Nino and I are celebrated. It just is an example of

what life is like for a Fulbright Scholar in Georgia. You

just never know what is around the next corner.

Days and weeks are speeding by. Already it is December and

my exhibition opens in twenty more days. Yesterday, I found

a printer at a reasonable price (after two outlandish bids

on the work where I was doing all the design work). I guess

that the printers make their profit on their design time

while I was trying to cut that out as a cost. I want a

brochure of twenty pages but at bids of $800 and $720 it is

out of my budget. Now, for a poster and a smaller brochure

it is $260.00 USD, a respectable bid.

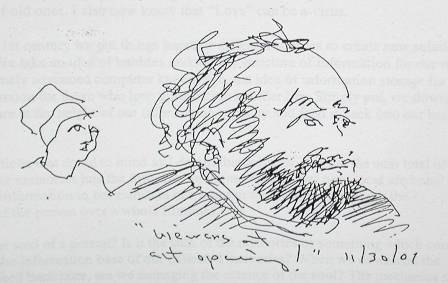

An American Supra, the title of my exhibition, opens to over

300 viewers. Some of my artists friends from Kutaisi come

and many of my students at the Academy, plus a few

professors. Afterwards, taking two bottles of wine with us,

we go to Loretta’s studio on the tenth floor of a concrete

disaster built by the Soviets. No electricity so the

elevator is not functioning. We eat fruit, some cakes and

drank wine, relive our time together painting and waiting to

paint in Kutaisi, and light a fire in Loretta’s new

fireplace. All of us escape coughing when the smoke backs up

but a good time is had by all the artists together again. We

talk of a spring exhibition called “Joe and Friends”.

It seems strange to get up in the middle of the night and

not have painting to do. I must rest my wrist from the wear

and tear of painting six to eight hours every day. It has

taken its toil. Plus I am preparing for other jobs that must

be done. The painting has been all-consuming. It has been my

work, my relaxation, my passion for the last three months.

It is strange not having it to do but that too is part of

the process. Even muscles need a rest before they work

again.

From the Georgian Arts and Cultural Center, I get an urgent

telephone call from Maka Dvalishvili, the Director of the

cultural center, that they finally have electricity so they

are going ahead with their Christmas sale. Today, a Friday,

they are printing the invitations for the Sunday opening to

sell museum reproductions which has taken three years to

assemble and create. She is almost in tears that they have

electricity at last. I could not live with this situation

for years as she has. You plan something special for your

museum and your country, you secure funding from Phillip

Morris Company, you select the objects to be reproduced,

have them made to specifications, and then be held up

because the government will not pay the electrical bill for

the National State Museum, where the Arts and Cultural

Center is located. Justice in Georgia is certainly blind.

The pattern continues. I wake at 3:00 a.m., work on the

computer until 4:00 a.m., go back to sleep, wake at 6:00

a.m. to return to the computer, and finally go to the studio

to work on the painting. This morning it is the text from

archeology digs waiting that Maka has sent for editing from

Georgian English to English English. It is more of a

challenge than I expected but I have given Maka my word to

help and I will. I thought that it would be an editing job

but it turns out to be a rewriting job. I complete it and

Maka has her opening on Sunday for museum reproductions. She

asks me to give a public speech. I will work on my

exhibition until 3:30 and leave early to make her event by

4:00 p.m. Nothing starts on time in Georgia so I have some

leeway. Of course, in this case, it did start on time. Just

as I have things figured out, someone changes the rules but

I come to the opening in the middle, give my speech about

the importance of museums owning archeological finds after a

period of research by the academic community. It is more of

a political speech than about art. It targets the members of

the Parliament who are in attendance and trying to create a

law saying that the individual owns national treasures

rather than the national museum and the people of Georgia.

When Raphael was driving by the river the other sunny day,

he stopped the car and asked, “Do I stop or go?” I turned

and the light was red and green. We watched it change once

to yellow and then again to red and green. Cautiously,

Raphael drove on but it is a wonderful symbol of Georgia.

Stop and go. Make up your own mind; move at your own risk;

and never take anything for granted.

The day has finally come. I go to hang the exhibition. All

is ready. There are some unknowns, like how can you drive

small nails into the concrete, but most variables have been

thought out, a floor plan for hanging has been drawn and as

much as possible all is ready. I am a “control freak” when

it comes to my exhibitions. Even my own painting is put

through an inspection before it is shown to the public. I go

over each inch of the work with a magnifying glass, looking

for small things that need corrected. It has always been

this way. Sitting at a table for a meal, I find that I begin

to arrange the knife, fork, spoon, etc. and the spaces

between each object.

I have been reading “The Horse’s Mouth” for the umteeth

time. The book is literally falling apart so I leave pages

of it all over the house, in the Embassy, at restaurants,

everywhere. Gulley Jimson, the artist in the story, would

have approved of the book’s demise. I appreciate his

descriptions of the artist’s vision and I love his passion

for seeing. Joyce Cary understands the mind of the painter.

Gulley is an artist in his sixties. I am an artist in my

sixties. He lives his life as a free spirit. I live my life…

The parallel are striking and I can look through Gulley’s

eyes as if they were my own.

As I sit here writing, I find that our decision to fly home

for Christmas is not just right but critical. When I went

recently with Nata, the Cultural Affairs Assistant at the

Embassy, to view the copy for the exhibition brochure, she

went one way and I returned to the apartment. She found me a

taxi, told the driver where I lived and set me on my way.

Halfway I realized that we were going in the wrong

direction. There had been so much talk about kidnapping of

Americans that I had to calm my nerves before gesturing to

the driver, “The other way.” I had been to Rustavi, about

twenty miles from town, and that is where we were headed. At

another time in my life and another time in history, I would

have let the situation continue to see if a new adventure

could be found but now I wanted to be where I felt safe. A

German diplomat had been murdered with a rock two nights

before as he got into his elevator to go to his apartment. I

knew one word for direction, “Adjara Hotel”, which was

across from our apartment. With gestures and that one word,

the taxi was turned around and we drove home. He charged me

for his mistake as I got out of the taxi but I did not care.

This is typical of life in Georgia at this moment in time,

for a foreigner in a land away from America after September

11th. All you want is routine. No surprises. All you want in

Georgia is safe passage from point A to point B.

Today is finishing day at Caravan-sarai Gallery. We take the

painting from the Embassy ballroom as the center piece for

the exhibition plus all the work from the apartment. Anne

and I finish what a team of us started two days before. It

takes three and half hours to complete the hanging, get up

the signage and make last minute adjustments. We have many

visitors as we work. It is freezing and the cold finally

gets to me. The walls are at least five feet thick and

retain the night’s chill for the day. On the way home, we

stop again at the Embassy to get warm and to use clean

bathrooms. The toilets at the museum are holes in the floor

and dirty.

The opening is a normal one for Georgia: a large crowd,

interested and perceptive. I have seven to ten interviews

for television, radio and newspaper, sign over one hundred

signatures on my brochure, and talk to individuals who want

to know what this all means. The idea of “Joe and Friends”

gets a push toward reality as Nino, the art critic, decides

that she will curate it. She decides to ask all the artists

who know me from around Georgia to exhibit with me. I am

honored that they care but so tired from the preparation

that it is hard to really enjoy the event. I hired Raphael

and two of his musician friends to play gypsy, Georgian,

Russian, jazz and show tunes. I do not even have a moment to

listen.

Was the exhibition as good as I want it? Yes. Could some

more detail make it better? Yes. But this is Georgia and

nothing comes off totally as it is envisioned. That is the

present tragedy of this country. You cannot plan ahead and

yet you must try. I had drawn the floor plan, selected the

placement of every work, devised a system of hanging panels

between pillars from wires (which Raphael and I bought at

the bazaar), conceived of how the individual pieces could be

hung so that taking it down when I am gone in America would

be simple, and wrote all the copy, having it translated and

the placement on the wall. With all this planning, there

still are adjustments but I did get it hung in two days,

which I was told was impossible, and had a successful

opening from a personal as well as a professional point of

view.

My Georgian artist friends are surprised at my planning.

Planning is not an art that is practiced because of the

frustrations when the event is ruled by factors beyond an

individual’s control. I understand the frustration murdering

initiative but I will never accept it as a way of life.

There is always a way. Contemporary Georgian life is closer

to the existentialist way of living that I once professed in

my youth. Living in the moment is still a glorious way to

savor each segment of living, but I now also believe that

luck comes to those who are prepared. It is my tradition to

plan. From a free society comes hope. In Georgia, tradition

is the one thing that has held this society together as it

was attacked from all sides. Georgia stayed Georgian through

its holding onto traditions. Now that the attacks are not

here, traditions must grow or die. That is why I called the

exhibition “An American Supra”. The supra is a ritual for

celebrating all that is enriching in life and all that

should constantly be held close: freedom, country,

childhood, mountains, heroes, the future, play, love, color

and form, those who have died, icons, family, and being

truly alive.

December: Letter from Tbilisi

Letter from Tbilisi: As the Christmas holidays approach,

thoughts go to old friends in America and new places, people

and ideas which have been given us in Georgia- mostly good,

some not. One afternoon at the Black Sea when we were

looking for the perfect snack, a vendor came around with

ears of corn. It was so fresh, tasteful and delicious that I

wondered why it had always been presented to me only with a

full meal.

Once in Kharagauli, I saw that there was water leaking from

under the sink. I looked. There was a bucket to catch the

drainage. Americans take so many things for granted: like

plumbing, electricity and water. In Georgia none of these

things can be assumed. In fact, the opposite is true. I

write this in the middle of the night because this is the

season of “black outs”, loss of electricity and no tap water

all over Georgia.

I feel during the last few months that I have stepped into

the 19th century. The impression started when we

walked into our apartment in Tbilisi that first night. I

could see Renior or Monet living here in the mid 1860’s.

When I worked with artists in Kutaisi in September, we went

on outings like the Impressionists. Reality has changed

since then (although it is refreshing to step back in time).

It is no longer only that which is outside the eye but also

what we know, what we dream and what we imagine. A Georgian

artist told me that this kind of thinking is called

“foreign-born” and “liberal”. Georgia at this time in its

history works by “hurry up and wait”. The dominate color in

dress and life is black.

One of the first things that I, as a man, had to learn is

the rules of the Supra, the traditional men’s toasting

ritual. It happens almost at all times when Georgians gather

to eat and drink. There is a pattern controlled by the

“tamada”, a wise and flexible leader who runs the

celebration dinner like a conductor of a great symphony

orchestra. The best that I have witnessed is Shasheasvili,

Governor of 14 districts in Western Georgia and great

supporter of the arts. He went through toasts to guests,

America, Georgia, family, parents, grandparents, those who

died, artists, special persons, peace, love, women, and

other creative subjects (all this over an eight hour period

while he had to drink twice as much as anyone else). Our

shortest public dinner so far has been two hours.

The poverty in Georgia tears at your heart. Those who toil

so hard to change this receive little salary in return. A

few examples are: the President of Georgia makes $2000 lari

a month ($1000 USD), the governor of a large district: $230

lari ($115 USD), the Governor’s driver: $70 lari ($35 USD),

the Director of Water for a city outside of Tbilisi: $14

lari ($7 USD), and a teacher in the provinces: $40 lari ($20

USD). The pension waiting for my Georgian artist/professor

friend on reaching 65 is $7 lari. I could not tell him what

I get from Social Security. As Sasha, a farmer, told me in

the mountains: “All we have here is hope.”

A vivid image that stays with me at this special time of

year is Motsameta and its priest, Father Mamao. Perched on a

strip of land, 500 feet above the stream and valley on three

sides, this 8th century church stands as a vivid

image of strength and the determination of the Georgian

people to survive and thrive against war from all sides and

the ravages of time. I met an 89-year old priest, whose

laughter and wit are as clear as his long while beard. He is

guarded by his location, God and four “sometime-loving”

Doverman Pinchers. He is a legend in Kutaisi, walking

barefoot on special religious days from the town to his

oasis on the mountain. He makes his own beer and writes

poetry in his spare time. Recently, he visited relatives in

San Francisco. I still picture this imposing figure, long

white beard and pastel robe flowing in the bay wind, walking

the modern streets as a figure out of time but timeless. He

showed Anne and I two paintings of saints that he created

for the church (other precious paintings and church icons

from the 8th to 12th century were

saved by the people of his parish during the Communists

purges of all religions and religious objects). Words cannot

describe the twinkle in his eyes and his smile of

contentment. For those looking for “peace on earth, good

will to mankind”, look no further than the face at Motsameta.

Yes, there is a Santa Claus. I found him in Georgia.

January: Letter from Tbilisi:

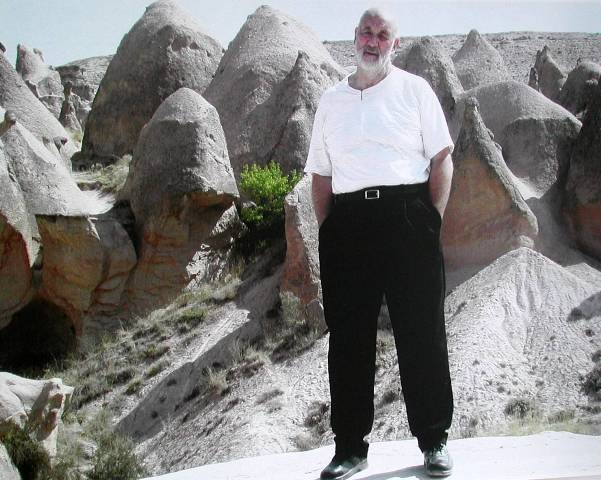

Before coming to Georgia to teach American art and

architecture plus museum studies at three universities, and

lectures on Chinese art, American art, American architecture

and museum management at two national Georgian museums and

to Georgian architects, I was ready for a short vacation. We

decided on Istanbul and Cappadokia, Turkey.

Istanbul is the end of the silk road which starts in China,

crosses Tbilisi, Georgia and terminates in Turkey’s meeting

place for Asia and Europe. Divided by the Bosphorus River

which joins the Black and the Marmara Sea, Istanbul has been

an important crossroad for trade all through history and

many nations fought to control it. We sail the Bosphorus and

marvel at the grand palaces on each side built by the

conquerors and rich traders. We walk through the vast, open