|

American Supra: Book Four

Christmas In America,

Return to Georgia,

Teaching, Projects, Grants, Lectures, People,

Events and “Joe and Friends”, an April Exhibition

Blest hour! it was a

luxury- to be.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge,

1772-1834,

from Reflections on

Having Left a Place of Retirement

To love one maiden only,

cleave to her,

And worship her by years

of golden deeds.

Alfred Lord Tennyson,

1809-1892

Give me your tired, your

poor,

Your huddled masses

yearning to be free,

The wretched refuse of

your teeming shore,

Send these, the homeless,

tempest-tossed, to me;

I lift my lamp beside the

golden door.

Emma Lazarus, 1849-1887

In life courtesy and

self-possession, and in the arts style, are the sensible

impressions of the free mind, for both arise out of a

dsliberate shaping of all things and from never being swept

away, whatever the emotions, into confusion or dullness.

William Butler Years,

1865-1939, from Essays and Introductions, 1961

Tbilisi 5

It is the day before Christmas. We have our present already,

coming home to spend time with our children and friends. It

will be easier going back to Georgia.

On the night before Christmas, we have spaghetti, beer and

wine. I try to give a Georgian toast but it just does not

work.

On early morning Christmas day, I sit here in the living

room with the lighted tree and all the wrapped presents

until others get up to begin the ritual of opening gifts.

This season I am more interested in giving than receiving.

We will see how that plays out. Christmas is a time where

Samantha becomes a child again with the excitement of the

season (and now she is a 31 year-old mother). She will pass

this joy to Erin I am sure, just as we passed it on to her.

Yule time is a magical season, much more than the presents

under the tree. It is the songs of Christmas, the atmosphere

of counting our blessings and everyone on the street saying,

“Merry Christmas.” Coming home is the best present we could

give ourselves. As one friend told me long ago, “After the

money is spent, you forget its amount.” The wonder of the

work in the new exhibit on December 19th begins

to fade. “What’s next?” is my mindset. I am beginning to

think of the spring exhibition, my final showing in Georgia.

How do I top what I did in December? I don’t but maybe Joe

and Friends will be a new experience as rich as the last (as

all my Georgian artist friends come together to say

goodbye). It should have wide public appeal and show the

variety and skill of what is happening in Georgia. That

will make three major projects for the spring: finalizing

the placement of the American Art Archive Collection,

creating the first playground in the inner city in Tbilisi,

and the “Joe and Friends” exhibition. That is plenty to keep

me occupied until we fly to Beijing in May and then home to

Texas.

We get a rare treat on Christmas afternoon, an encore

performance of the Concert for New York City. It is five and

a half hours of pure pleasure and tears. I do not like all

the music but no one can deny the wonder of the whole

experience of America coming together to mourn those who

died and celebrate freedom. It is hard to find the words to

say how I feel. There is pride in America, certainly, and

there is wonderment in how

quickly America rebounds from the terrorist attack. I think

that bin Laden thought that the structure of the nation

would crumble when the two towers did, but he is wrong. We

are only soft on the surface. The Rumanian columnist’s

article on America, sent to me from the Rumanian Embassy in

Tbilisi, sums up my feelings in his “Ode to America”. He

calls the five and a half hour concert “a celebration of

freedom and heroes”.

Since that concert, I have been thinking about America’s

position in world affairs, particularly in light of

international terrorism. I know that bin Laden understood

that he was attacking a symbol of America’s wealth and

power, but what he might not have see is that America is a

system which does not depend on the leadership from the top

but the courage of all citizens when freedom is attacked. It

is the system which will survive, even when individuals die.

It does not make any difference in our policy if Gore had

beaten Bush for the Presidency. The job shapes the man

through our history as it does today. You can see that in

the faces of those who have been chosen to lead. They age

and gray in the decision-making position. In Georgia, if the

head man changes, the system changes. I also question bin

Laden’s decision to attack the World Trade Center because

the optimum word there is “world”. It is interesting to see

that all attacks since then have been on American Airlines

or the US Postal system. Certainly, there is an attempt to

separate America from the world by the terrorists, but the

logic of killing sixty different nationalities in the Trade

Center tragedy escapes me. America is no longer protected by

isolation. That is now clear but in turn it is now a partner

in a world without borders. Green is the color of

international business and bravery is the color of freedom.

Now, it is the last day of a year of turmoil for the world

and adventure for us, mostly good but some not. It is a year

that set us on a course that we needed as a break from what

we had been doing. It has not been an easy year, but nothing

worthwhile is easy. My creative work is at a quality height

that I have wanted for some time and my work has been shown

internationally. Returning to Tbilisi, Georgia, to finish up

the teaching and all the other projects will not be hard. In

fact, it will be much easier than if we stayed there over

the holidays.

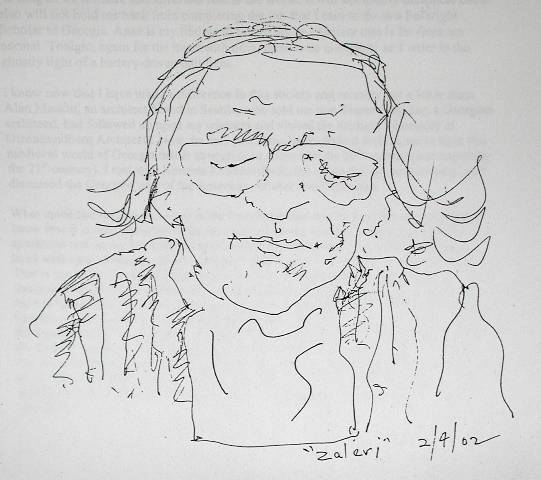

Every morning I wake to the lithograph of Matisse’s drawing

of a woman’s face, the essence of beauty and simplicity. The

line work captures all the elements that traditional

Renaissance classical drawing conveys. It does what I saw in

the classic beauty of the faces of women in Georgia. This

morning I try to draw it from memory, a memory device for me

to etch it in my mind. It is the same device that I used in

Kutaisi to learn the names and faces of the artists with

which I shared a month. I see the little upturn of the line

at the edge of the mouth, the long pure line of the nose

(ending in the small hook that directs attention back to the

mouth), and the almond-shaped eyes that stare out at the

world with child-like innocence. The line of the hair pushes

in upon the oval of the face. It is so perfect and complete,

just the right combination, just the correct proportions,

and just the ultimate degree of confidence in the line. I

did three sketches and only came close on one to what

Matisse had so easily done without seeming effort. I marvel

at his genius. Picasso, another artist I admire, used

innovation in his drawings to astound his viewer whereas

Matisse uses subtle line and unerring craft. He is the

master of the line. It is a wonder that a man could capture

the plastic unity of a woman’s face, hold it all together

and share that beauty in a few perfectly chosen lines. I

remember the men standing around in Tbilisi and the peace

and openness here.

Being with my daughter’s family for this special time of

year, I think that all of us have come to the same

conclusion: family is important and our differences are not

(although we honor those differences).

To end our stay in America, we fly to Pittsburgh on Friday

and on Saturday, Anne and I celebrated our 45th anniversary,

high above the city and its lights on Mount Washington.

Below is the meeting of the three rivers, Phillip Johnson’s

glass masterpiece of the PPG Center and memories of earlier

times when all of us were young. Lou, my brother in law, and

I ate at the Oyster House on Market Street, across from the

market where my grandfather sold fish. It is a place where

my father took me many times. They still make the largest,

most delicious fish sandwich in the world. The waitress is

still a “smart aleck” but now quite old (ancient, in fact).

Memories of good times flood my mind. Why is it as we age

the good times prevail in our digital memory unit, the

brain?

The anniversary dinner is paid for by Anne’s sister and her

husband, Lou. It is expensive, over $150.00 for the four of

us, but I wonder if Georgian prices are coloring my vision.

This is the beginning of a journey back to Georgia. I now

places in the mind’s file case our American visions and

compare them to Georgia.

On the way back, I find that travel is not as much fun as it

once was. Security is high everywhere now. I am searched

three times, twice by taking off my shoes. There is a

tension in the air. People are afraid that they will make a

mistake and they make mistakes. One couple on the plane got

very upset when an Indian couple changed seats, with the

permission of the stewardess, and he had to sit beside them.

Another man who saw the interchange gave up his seat so that

they could sit together but the first man was still uptight.

While relaxing on the airplane, I ask myself, “What had been

accomplished on this stay in America?” Rest is the first

answer, while relaxing the inner life as well as the body.

We viewed three exceptional movies. I cataloged, cropped and

enhanced all my photographs from Georgia and created several

slide shows for the computer. I played with my new visual

computer toy, which I will turn into paintings on arriving

back in Tbilisi. Mostly I go back to Georgia refreshed,

knowing what must be accomplished and ready to do the work.

On the nine hour flight from Detroit to Amsterdam, I find

that time is a subjective dimension. An image flashes up on

the television and movie screen, stating “Ten minutes to the

movie.” Having nothing else to do and nowhere to go, I try

to count the seconds in my head for a minute. I come to the

conclusion that air time is longer than actual time. I

mention this astute observation to Anne, who has a science

background, and she hands me her watch without a word. I

time the minute again. Of course, it is exactly one minute

by the watch. Now with the 600 miles to Amsterdam, I know

that my psychological time is different than real time and I

think, “We do crazy things to pass the time.”

Early morning has become a routine for me, waking with the

sun and the sounds of 1.6 million heartbeats of Tbilisi.

Being back in the city is easier and harder than before. I

have none of the adventurer’s illusions. I will just add to

the knowledge base of a few key players and students which

might make change happen in the long run. Tbilisi is an

overpopulated city with an unemployed male workforce that is

dynamic ready to explode. As I drive the streets with

Raphael and Anne, I see it in the park and at the bazaar. In

the few months that I have left here, I will built the

playground, establish the American art resource library,

teach my classes in museum management, American art and

architecture, and 20th century art criticism,

help the non-governmental agencies and the art gallery

owners to work in a free enterprise world, and create a body

of work to exhibit in “Joe and Friends” in April.

As we stroll along Rustevili Avenue, every ten feet there is

a beggar. Going under the street to get to the other side,

there are mothers with rag doll children in one arm and a

hand out with the other, out of work musicians play for

their hat of coins, and small shop keepers try to make a

meager living. Anne always puts something in an extended

hand. I mention all this because the contrast is so great

when you take your seats in the Opera House. It is always

filled. The tickets cost from 5 lari ($2.50) to 20 lari

($10.00 for an expensive production) but it makes no

difference in the cost. It is always filled to the fifth

tier of seats. Mothers and fathers bring their children. I

am still astonished by this. This image of support will stay

with me when I go back to America. Here are a people who

love art so much that they want their children to love and

enjoy it too. Tonight it is Carmen with, again, a full

symphony orchestra. In all the seats, everyone is dressed

with style. No beggars here.

I watch one man a few seats away keeping time by clasping

and unclasping his giant hands. He is a gargantuan hulk of a

man with layer upon layer of flab and a shape that surrounds

his seat like a snowman. Carmen is arrested and led off in

chains as the first act ends. My giant of a man hangs his

head in despair and rings his hands together. Sitting in

front of him is one of the most beautiful women that I have

seen with clean lines, olive skin and keen appreciation of

her looks and carriage. She holds herself apart. The man she

is with does not fit her therefore I question whether she is

a woman for hire, a bangle on the man’s sleeve for the

night. Sometimes I wish that I could read minds but here I

can read small gestures, lines and actions. It is most

interesting, a play within the opera.

No electricity last night and none briefly this morning.

Across the street, in the Adjara Hotel, the lights are

always on and they never pay any bills since they are

refugees the government puts there. Anne had enough time to

complete one load of clothes before the electricity went off

again. She feels fortunate since the other day it stopped in

the middle of drying and she had to wait eight hours before

she could finish and unload the washer.

Of course, there is no electricity today so we go to the

Embassy (who always has heat, light and electricity). We

went for several reasons but one main one was to retrieve

our bill for our cell phone so that we could pay it. A

normal request. We wanted to pay our bill. It could not be

found. “Well, call the company,” I say, “find out what I

owe.” Simple, right? Simple, no! “They can’t tell you,” I am

told. “Why?” “I don’t know why. Give me a day or two and we

will bill you again by sending a fax to the Embassy.” Did I

mention the answer that I got the other day when calling the

Sheridan Hotel to find out what time Rotary holds its

meeting? I was told in the most serious voice, “They meet

every Wednesday night at 6:00 o’clock if they come!” Well,

to finish the story, after we paid for our cell phone, we

got the lost bill.

We go to dinner, 2:00 p.m. in the afternoon, at Raphael’s

house for soup and bread. We told him to make it simple.

Have you ever had a ten course soup and bread, with extras

of course? Across the table sat Raphael’s brother, Volari.

His face says volumes about the harshness of life in

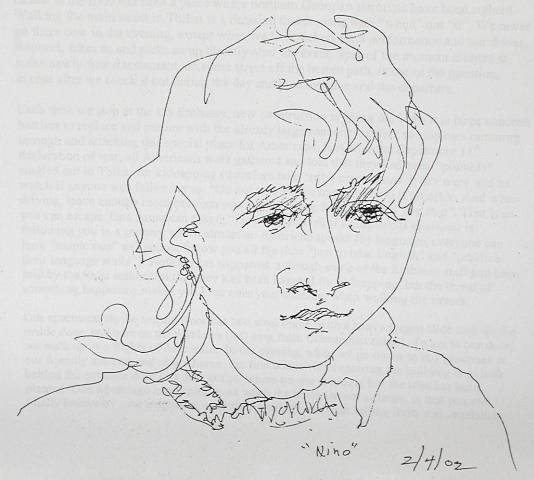

Georgia. The innocence of Nino, Raphael’s niece, is in

contrast to the weathered face. Her youth is fleeting so I

wish to catch it before it becomes the morning mist and is

gone. The lovely Julia, Raphael’s wife, voices her opinion

about the problems with electricity. “Some days, I don’t

want to live here anymore,” she said. “Everything is too

hard. The lights are out, no heat for days in the winter,

Michael cannot study or go to school when it is this cold

inside, and the corruption keeps it all going. Some say it

is the Mafia of Georgia that sells the kerosene. Electricity

is cheap; kerosene is expensive.”

Volari adds, “This has been a mild winter and yet the

electricity is off when the businesses are opened.”

Raphael’s only comment was “Crazy people.”

When we were in Waco at Christmas time, Anne picked up a

copy of Senior News. Don’t know why she did that since we

are so young but she did. On the back of the section for

which she picked it up was a letter from a 75 year-old man.

He writes: “We are, considering the alternative, reasonably

content with the burdens of functional obsolescence, such as

the immediate transfer of desserts to bodily blubber, the

nearly as immediate metamorphosis of most foods from solid

to the gaseous state, the graying and decaying above the

neck, and the widespread deterioration below it.” I still

chuckle at this old man’s words. I am so young, a mere

sixty-nine, yet I empathize with his words.

February: Letter from Tbilisi:

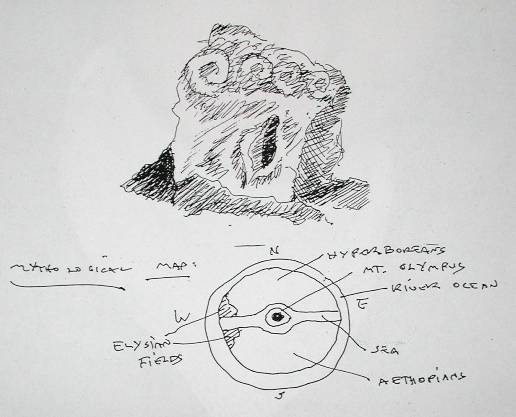

One of the reasons that I wanted to come to Georgia was to

see wonderful examples of Byzantine and Georgian

architecture of the 11th and 12th

century. In front of an ex-hotel which the Russians built,

in the center of Tbilisi, now filled with poverty-stricken

IDPs (Independent Displaced Persons, who are different than

refugees who come across borders), stands the grand statue

of the Bagraid king David II Aghmashenchechi (1089-1125).

Each time we pass, my driver Raphael points out how he,

although only 16, defeated the Seijuk Turks at the Battle of

Dadgori in 1121, ushering in Georgia’s golden age of

architecture. This period was short-lived for the Mongols

came sweeping through the South Caucasus in the 12th

and 13th centuries. What followed are the Ottoman

Empire and the Persian invasions, interspersed with brief

period of freedom, and then the iron grip of the Russians

from the 18th century to 1991. All that one can

call Russian utilitarian structures is “concrete ugly” and

the worst form of architecture for humans to live within.

The hotel behind the statue of King David is a good example

of bad architecture and Georgians shake their heads because

the Russians left many examples of that.

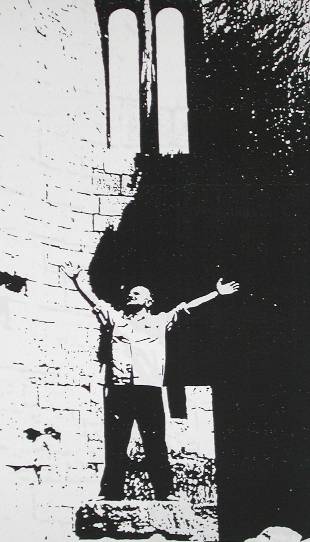

On the hill, grandly overlooking the city of Kutaisi, stands

Bagrati Cathedral, a church built in 1003 A.D., destroyed

many times and rebuilt. There is a long winding, cobblestone

road to the church which is walked by the citizens on holy

days. We walked it when the yearly procession of the

Madonna’s icon, the city’s official relic, is taken to the

church. Standing in the services, the sky as the only roof,

you feel like you are in grand open air Gothic cathedral,

although the rounded arches tell you this is pure Romanesque

architecture. In this structure, you can see the improvement

in opening the walls with arches when contrasted to the

Kharagauli church built in the 8th century where

the structure is more closed in although the cupping out of

space has begun. Frank Lloyd Wright calls architecture “a

womb with a view”. The close space and semi-domes cupping

out cave-like areas of the Romanesque style do give a

feeling of sheltering comfort. Anyone thinking about it

knows that “mother” is the first home, the cave follows

shortly, and then constructed structures to keep out the

elements and retain warmth and coolness.

In Eastern Georgia (Bagridi Cathedral was in Western

Georgia), Georgian homes from earliest times had roofs which

tapered into a central hole which let light in and smoke

out. This design, the darbuzi, may have been the origin of

the central-domed churches so typical of Georgia. In “old

town Tbilisi” these churches still exist is wonderful

condition.

Therefore it was with great interest that I went to see

Victor Djorbenadze’s “Wedding Chapel”, on the left high-bank

of the Kura River in Tbilisi. Rolf Gross makes the

statement, “Victor Djorbenadze was one of the remarkable

architects of the end of the 20th century…the

Wedding Cathedral shows him to be one of the great

architects of Europe, with a sophisticated architectural

brut, which orients itself on Le Corbusier and Frank Gehry.”

That is high praise indeed. Le Corbusier was the main

architect of the International style which made the glass

buildings of New York, Dallas and Houston possible and Frank

Gehry is the originator of the revolutionary Guggenheim

Museum in Balboa, Spain.

It is a miracle that this work of art was built at all.

Djorbenadze was a homosexual in a culture where that is

unofficially condemned. Fortunately, he was backed by Edward

Shevardnadze, present President of Georgia but then chairman

of the Communist Party (a act of courage on Shevardnadze’s

part because Djorbenadze was not a member of the Party). The

castle-like outside, sheathed in limestone facing, is

spectacular but the inside is purely Georgian with rounded

curves (similar to Georgian letters and the Georgian love of

“mother”). When asked about the floor plan, Djorbenadze

confessed that the female reproductive system was his basic

form.

Djorbenadze’s cathedral has been somewhat ignored today

because of the Georgian justifiable dislike of anything

“Russian in design” but this building, although built under

Russian rule, is pristine Georgian. Looking up into

cross-wise overlapping wooden beams that form a “false

dome”, one is reminded of those early cone-like structures

of Georgian farm homes (which can be seen at the Tbilisi

Open Air Museum and in Miskheta). Victor Djorbenadze died

forgotten and disparaged in 1999. The neglected Wedding

Cathedral is slowly crumbling. As Rolf Gross writes, “There

is nothing like it in the former Soviet Union”. But as a

wedding cathedral, it may have seen its time. There are too

many unpleasant memories of the Communists repression of

Georgian Christianity. Georgians are returning to their

traditional churches for services and marriage (as it should

be) but it is time to rehabilitate the man and find a new

use for this original and remarkable work of art.*

Internet source for images:

http://vdjorbenadze.tripod.com/WC02.htm/WC03.htm

* Typical in Georgia, instead of the government finding a

use for this national treasure, they sold it in 2002 without

a public bidding system to a Georgian millionaire who made

all his fortune in Russia. He is now living there and has

made it his home. The Georgian people are kept out by steel

gates and machine-gun armed guards. The more that this

society changes; the more it stays the same. This is the way

it was done in Communist times.

March: Letter from Tbilisi, Georgia:

This is one story in a nation of stories.

Just up from one of the two McDonald’s restaurants (with a

happy Ronald McDonald in full color sitting outside with his

hand raised to greet the many patrons) is an old cobblestone

street with houses behind large steel doors and an

atmosphere of stepping into the mid-19th century.

My co-teacher, Ketevan Kintsurasvili, who shares a class in

Modern Art and Criticism with this American Fulbright

Scholar and allows me to call her Katie, had asked Anne and

I to join her when she went to visit the studio of the

Georgian artist, David Kakabadze. His widow Etery

Andronikashvili keeps the spirit of his art alive in this

house. Etery also teaches at the Tbilisi State Academy of

Fine Arts

The studio was on the second floor. Etery met us with a kiss

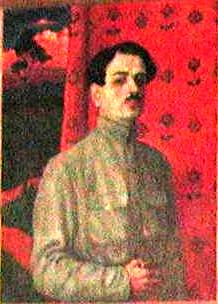

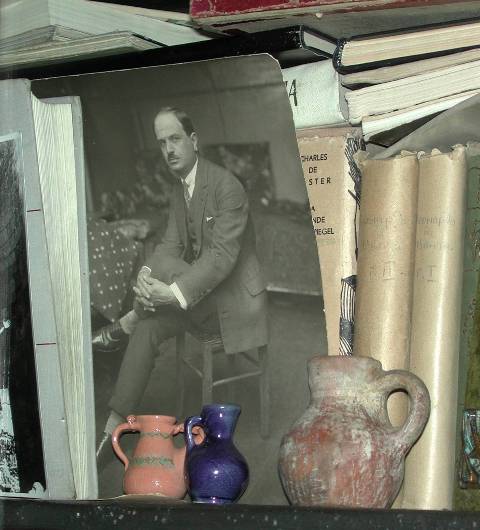

and said, “We begin to see here.” And see we did. A portrait

of her husband done in Moscow in the early 1910s met our

eyes as we stepped into the room. It was of a proud,

straight-shoulder young man with a small moustache looking

assuredly out at the world. Next, we saw his early paintings

of Georgia and his love of the mountains was clear. In fact,

his love of Georgia showed through the paint which was, to

my first surprise, ahead of its time. He bathed the

mountains in color and spirit.

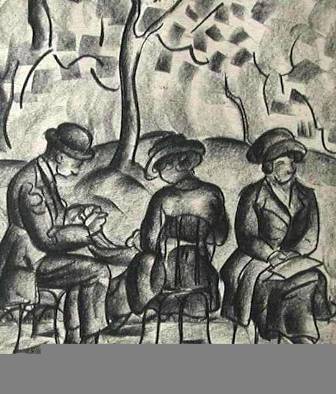

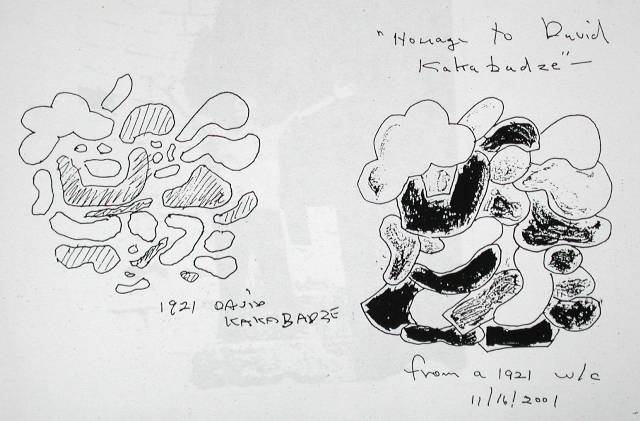

Now came the second surprise. I had journeyed to Tbilisi,

Georgia to learn about the art and its people. All the

research that I did before coming told me that the art was

about 100 years behind the times, black and white with a

little color thrown in and no modern art concepts. When

Kakabadze went to Paris in 1921, he was a leader in the

Cubist movement, exhibiting alongside Picasso, Braque and

Leger. Long before Kandinsky finally came to Paris in 1930s,

Kakabadze was doing biological cubism with images that came

alive under an artist’s microscopic eye. Kakabadze had been

trained as a biologist as well as a painter. His work was

not of cubism but went beyond cubism in its concepts.. The

excitement that his work created, being so far in front of

what was happening in the early 20th century,

made me want to see his studio in the next room. If a man

can create all this from 1921 through 1927, what miracles of

art could he create for Georgia when he returned in 1928?

His revolutionary historian friend who lived several houses

away tried to get word to Kakabadze that he should stay in

Paris. “The Soviet Regime is oppressive and does not allow

any new ideas to flourish in Georgia” was the message. But

the young artist could not believe how bad the situation was

in his beloved country so he returned.

The first thing that the Soviets did was outlaw any painting

of Cubism by Kakabadze or any other modern ideas about art.

Only Socialist Realism was allowed. If a young painter

wished to feed his wife and children, he painted the party

line. It was impossible for him. Cubism kept coming into his

compositions. He had secured a teaching job at the Academy

where I now teach. He was popular and loved by his students

for his understanding and ideas. Yet, he was forced to teach

only Socialist Realism and in 1948 he was dismissed because

he was not a zealot of Socialist Realism. He was banned from

any profession to make a living. He lived from the kindness

of strangers and friends. This lasted for four years until

his heart gave out and he died in 1952. Oh, I forgot to tell

this part of the story. All his students got failing marks

because they had associated with or taken a course from

David Kakabadze.

No American can imagine what this hero of Georgia went

through for his country. He had to silence his ideas about

art (which were beyond their time and at the edge of what

was happening in modern art), give up his teaching and

finally give up his life just because he returned to the

country he loved so deeply. The Communists would not allow

him to leave the country. He was threatened with death if he

spread “modern ideas” to the young. He was blacklisted so he

could not make any living from his talents. In Paris in the

1920s, the American Katherine Drier and her friend Marcel

Duchamp purchased many works by Kakabadze. They are some of

the treasures of the Yale University Art Collection, taking

their rightful place side by side with Picasso, Braque and

Leger. And now in Georgia, David Kakabadze is known as a

great artist, a patriot and a tragic victim of Communism. I

learned that the cobblestone street where his studio, his

widow and Ronald McDonald live is called Kakabadze Street.

When I journeyed to Rustavi to lecture at Highschool 23

and Rustavi State University, I was impressed that the

principal of the highschool had rallied the community

together and gotten the walls in the school painted. I was

going to turn in a grant which had a component for painting

to be donated therefore I asked her to write me a letter,

telling how she got the walls painted. What I received was

more than I asked for but it was so honest about life in

Georgia that I included it in my journal.

Tbilisi 6

Anne and I go to the Georgian National Museum, open from

11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m., which specializes in archeological

finds before the time of Christ. We have attempted this tour

four other times but each time the electricity is off. The

government has stopped paying the bills for lights and heat

although this is a national museum. This time we are

determined to view some aspects of the collection but there

is still no electricity for the upper floors. Only the gold

collection has lights; no heat but lights. We pay for our

ticket and a woman who speaks English consents to guide us

through the gold and silver treasures. She has worked there

for 35 years. The tour takes over two hours and we leave

only then because the museum is closing for the day. I now

know more than I ever wish to know about the art of

goldsmithing in Georgia but she is determined to be thorough

and we are determined that if she can take the freezing

chamber we will follow her. It is much colder there down in

the subbasement than outside (again, because of the

architecture and the practice of building four to five foot

thick walls to hold the night’s coolness which works if you

have some way to warm the air a little). As our legs get a

little numb from the cold, we journey on until a guard kicks

us out. The outside air is refreshing, feeling positively

warm in contrast.

It is time to return to an idea that started at the Black

Sea in September. I am fascinated still by Georgian letters

and words, not as a linguist but as an artist viewing pure,

sensual form. Here are the ones that started me on this

journey:

Today, Raphael takes me to the Embassy

for a computer briefing. Getting there early, I am asked by

the man setting up the computer, “Why are you here?” “I am a

Fulbright Scholar who uses the computers when mine is down

and I need to read my emails.” “You have no government

clearance.” I am sure that was a statement, not a question.

“All you do is get into Hotmail?” That was a question, I

knew, from the look on the man’s face. “Yes, I read

Hotmail.” “Then you don’t have to be here.” “OK,” I said

smiling, “I will leave. Someone said that I was required to

come to this before I could use the computers again.” At

this moment, a second man who had said nothing, pulls the

first man aside and begins whispering as I gather up my

sketchbook and pens. He returns before I am ready to leave.

“I’d appreciate it if you stayed,” he says in a government

tone which means ‘you better’, “officially, you do not have

to but I would appreciate it.” I sit down again, “OK.” You

get used to this in Georgia but as the King says in The King

and I, “It is a puzzlement.”

At the beginning of the briefing, the gentlemen who asked me

to stay begins speaking in “government-speak” with a lot of

IPOs, ISSOs, CLOs, etc. laced with words I understand but

not here out of context. I do not understand a word he says

for the first five minutes but the others in the audience

nod their heads so I know that the briefing is going well.

Oh, I get the gist of the message, “Don’t mess with my

computers or I will slap your hand. Here are my rules.”

The more that we become dependent on technology to do our

thinking the more we think like computers. He tells us that

computers can be scanned from a mile away if you leave them

on (if you have the right equipment, and the enemy always

has the right equipment). With me, the United States

Government is secure in its information. I know no

passwords. I know nothing. I am dependent on others to even

get me into my webpage on Hotmail. Most of what is discussed

is for the hired help. I am the outsider although they

include me in briefings where I get bits and pieces which

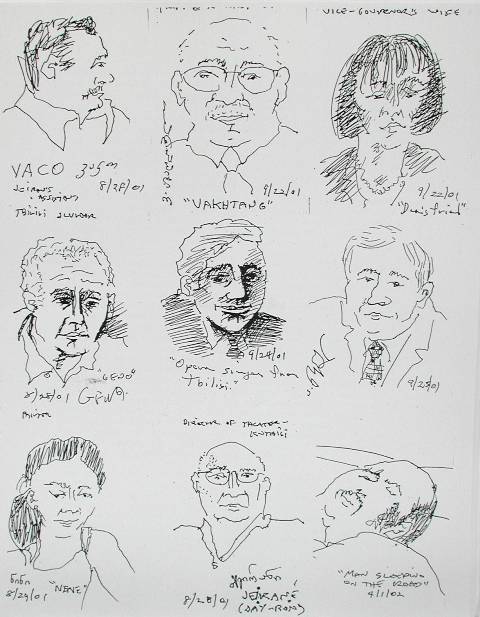

never go together. But I did not waste my time. I make

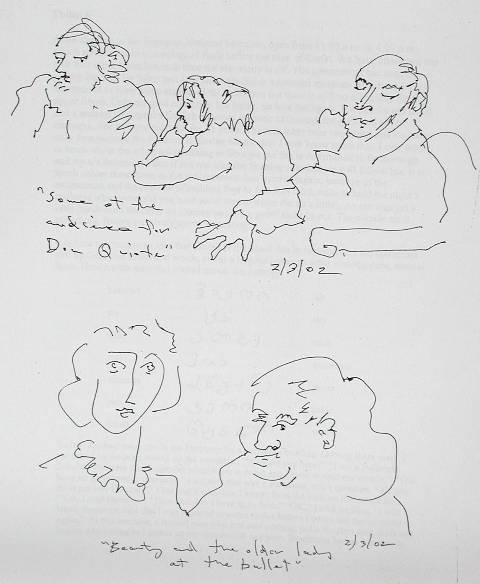

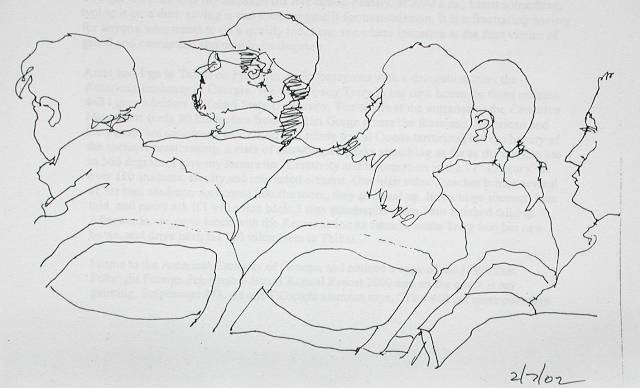

sketches of the audience. I get a lot of information from

him about how not to get information. My drawings are all

about gathering information. From a critical point of view

and as a teacher of over 40 years, I analyze his “non-style”

of presentation. The best that I can say is that it is

boring.

Yesterday, we went to the bazaar to try to find acrylic

paint (since all my paints were not allowed on the airplane

at Christmas because they were on a list of “flammables”,

which acrylic is not, oil paint is). After examining each

booth in the paint section, we found none. We went to Expo

Georgia and the German/Georgian paint company. I found

yellow and white in acrylic (liquid form but I will make

do). Ah ha, they do have the paint in Georgia. I had been

told that there was none here. It is German-made so it

should be good. I have not painted for over a month. My

wrist needed a rest and I did not wish to injure it further.

I will wear a wrist guard if it acts up again. I will tell

Georgian artists that they can find “acrylics in Tbilisi”.

As we pass the machine gun guard at the Mayor’s Office, we

enter a large hall with murals of Georgia’s past in tapestry

form on one wall and scattered groups of people waiting for

an audience with some bureaucrat. The Mayor’s office is also

crowded with those waiting to see him. They turn and

question our presence as the Minister of Foreign Affairs

shakes our hands. I am “the American” and his translator. We

are ushered into the Mayor’s grand office with a layout of

Tbilisi behind his desk. I give him the citation and the

present from the Mayor and City Manager of Waco. He gives me

a view of Old Tbilisi to take back to them. We discuss the

idea of a playground in the inner city. He queries if we are

here to ask for money. When we tell him that we have that,

we want his consent and blessing. With a grand wave of his

hand, he says, “You find the place, you build the

playground.” We leave and the Minister of Foreign Affairs

tells us to call him if we run into any difficulties.

The images of children’s writing on walls in our

neighborhood is put into the computer, enhanced, cropped and

made ready as visual data to use in the paintings. I have no

idea what they say but that is the beauty of the process. In

this case, further knowledge would color the vision of

seeing this writing as pure form. I do not wish to read it.

I wish to use it as visual enhancement for the surface of

the new paintings for the spring exhibition. I will never

see my own language in the same way. I know too much about

it to see it as if for the first time. I wish that I had

thought of this before the December exhibition. On some

paintings, it would have helped. There is immediacy in the

writing that is refreshing.

Sitting at a long table, the Rector, Vice Rector and three

members of the Art History Department sitting on one side,

Sharon Hudson Dean, Director of the Cultural Affairs

Division of the American Embassy of Georgia, Magda Madradze,

the Embassy interpretor and Assistant Cultural Affairs

person and me arranged on the other side, I get a totally

different reception than I have in the three months that I

have taught at the Academy. In fact, I got the royal

treatment with all telling Sharon what a wonderful person I

am and how much I have done for the Academy. This is in

marked contrast to the assistance that I have gotten to make

my job of teaching easier. I believe that it all changed

when I helped at the large meeting for the Rumanian

Ambassador and our lecture on Brancusi. After that, I am an

asset, not just a Fulbright Scholar from America.

The Rector was sure to tell Sharon about the history of the

Academy, dating back eighty

years which will be celebrated in May. It has 1100 students,

mostly from Central

Georgia, but actually all over Georgia. Later, I get to see

locked areas of the Academy

which had been closed to me before this, such as the

collection (which they now want me

to catalog). I tell them that I will use my students, train

them, and begin the process but

the job is something which will take several years (and I am

leaving, for sure, in May). It

is a nightmare of a collection. They have just left it sit

for 10-12 years or longer with no

covering to keep out the dust and no temperature and

humidity control. There is dust,

dust, and more dust over everything. I did get a promise

that all students would use the

American Art Archive Collection if I attempted this

impossible job. I do trust

the people I teach with in the Art History Department. They

want to have this dream

come true. Next Tuesday, we decide on a room for the

American Collection. Next Friday,

I start on the Academy’s cataloging nightmare.

I spend two days interviewing candidates for the Junior

Faculty Development Program to send Georgian faculty to

America. It is administered by the American Council. Over

the two days, a Georgian professor and myself thought that

we had six top candidates, out of twenty-one, for four

positions. The final decision will be made in Washington.

One excellent faculty member who teaches film and acting

told a story about finishing her movie which was praised

finally at the Cannes Film Festival, Moscow Festival, St.

Petersburg International Festival and the Kiev World

Festival. She told a story about making 15 to 16 films a

year in Soviet times, with the backing of the Communist

government (not everything was bad then). Now in the last

ten years, only six films have been created and she did two

of them. The Georgian government has put no money into a

film industry which was world class for years before the war

for independence. We asked her, since she was applying to

study arts management in America, how she got her film

finished that won so many honors. She said, “I went to all

the sources that I could find but for two years I had no

luck. Finally, I found a man to back my film.” Naively, I

asked, “And he was a patron of the arts? In the States, we

call that ‘an angel’.” “No,” she said with straight-forward

honesty and a serious look, “I sold my flesh.” I glance at

my co-examiner and she did not make any reaction to this

statement. Obviously, she has heard stories like this

before.

After that, I would have given her any scholarship to

improve herself and her exceptional art. There must be

stories like this all over Georgia. My partner just shook

her head, “Yes,” and went on to the next question as if the

young woman, age 50, had said, “I received a grant which

took two years to successfully obtain!” This woman is a

survivor where survival is king and queen and pawn and

everything. Americans cannot understand the dignity with

which this lovely, strong, courageous woman said, “I sold my

flesh.” How many artists would give up something that

precious to pursue excellence in their art? She saved her

inner soul and her inner dignity as an artist and a person

but she sacrificed something too. Selling your flesh is not

something which should be looked upon as degrading but a

statement of strength in this case to move into the future

with her head high. Was I impressed? More than words can

ever say; more than anyone will know. She said those words

as if they are normal and matter of fact but each word is

filled with resolve and purpose. It says, “I will anything

for my art. My inner being is more important than my body. I

will do what needs to be done and will move on.” Her film

won an award at the Cannes Film Festival but for me her

greatest reward is her resolve to create something personal,

yet a film that transcends the individual to a universal

statement.

Now it is early Saturday morning and the sun bites through

the mists of a coming storm across the hills which roll down

to the ugly apartment buildings. The statuesque churches and

Mtkvari River look cold in their stillness. The wind rips

through any garments and if one takes off gloves your hands

instantly freeze (it seems). It is a Tbilisi cold, the kind

that cuts to the bone. There are three min-buses filled with

children and Embassy personnel driving toward the mountains

for a short ski vacation.

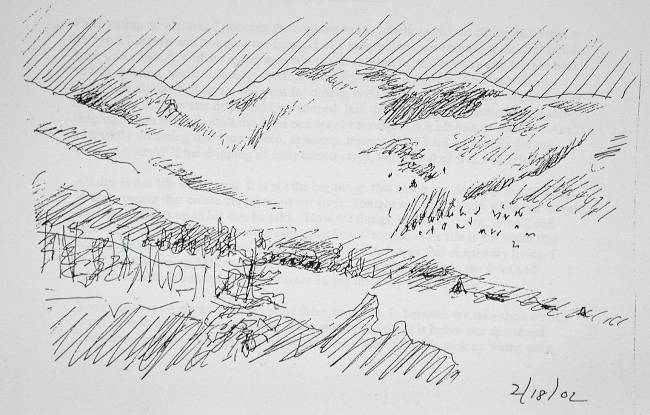

As we drive over uneven roads, the hills topped with snow

act as a frieze to the valley. The names tick by: Gori,

Alkabori, Ksani, Batumi, Sukami, like minutes and miles.

Ahead are the storms which are foreshadowed by the blurring

of the mountain tops as we drive toward Borjami (the place

of the mineral waters and the beginning of the “high hills”

which I call mountains). Nothing is a “mountain” unless it

is part of the Caucasus. As we drive into the foothills, the

ground is covered with virgin white six feet of snow. It

gives a visual meaning to the naked trees, dark houses,

silhouetted poles, brown weeds and a glimmer of grass that

seems to litter the landscape. Only the road is somewhat

clear but only for a time in this sea of white. The snow

drapes itself around the landscape like a royal robe.

Now the wet road is no more, just part of the whiteness and

more snow is falling hard. We are only halfway to the

mountain resort. If it keeps up at this pace, we will be

forced to turn back. Inside the van, it is warm and the

scene of beauty keeps our attention off an important

question, “If it gets worse, will we make it?” I am not the

driver who knows his job so I shelve that thought and

concentrate on the white scene which takes on its own glory.

On the side of the road a man stands waiting. For what, it

is not clear. In the streets of Tbilisi many men wait and

know not what for, except a job anywhere, doing anything.

Horse-drawn carts move slowly along the same white opening

between the fences and the trees. Merchants are still open

on the roadside, bundled against the blizzard that has now

evolved. We follow another mini-bus, pass stalled cars and

buses, but our movement is slow now. Suddenly, the three

buses stop at a rest station. Men and women run to the

bathrooms. The tile floor is slippery from the blowing snow

and the stalls are covered with layers of the new whiteness.

The sun is attempting to come out. It is clearing. We will

go on. The ice on the windshield is beginning to melt.

It is clear now. You can see the tops of the “high hills”.

The roads are still all white but the view of our

surroundings is crested by a muffler of soft mist. We drive

through sentinels of trees in stark contrast to the gray

“hills” beyond. The snow still falls and there is no

indication that it will stop but we know that we will make

the resort. Below in the rushing stream, a sole fisherman

stands thigh-deep in the freezing brown waters. On the other

side of the road, it drops off to a white field. Now we are

in the valley of the “high hills” with icicle-dripping rocks

on one side and the stream on the other. The road has become

a war zone of pot holes and small craters. Our driver is a

master of navigating this course. This is the same road that

we drove when we went to Kutaisi in August but it looks

different in its albino coat.

We climb and climb the high hills until three cars block the

road. Our drivers get out and help to move the stranded

cars. The snow at our sides is now four feet deep and mostly

untouched by human feet. Now, we step into the warmth of the

resort, the falling white snow, the shadows on the rolling

mountains and the silhouettes of houses, trees and people

are a black, white and gray painting by Whistler outside the

windows. It is one of his winter nocturnes. Snow purifies

the land. It gives it a cloak of ermine. As soon as we

arrived, we eat a simple meal. Tonight, it will be the same

at the Bakuraini Ski Resort.

When morning comes, pink mixed with a beginning blue emerges

over the Eastern rim of the Bakuraini Mountains. There is a

stillness here that the city will never know. The pace is

natural and normal. The beginning day is quiet and reserved

like an elderly gentleman rising with the sun. It is snowing

gently now after our walk to the village. The room is

painted stark white. We were instructed when we prepared for

the trip to bring sunglasses but I did not know that it was

for the indoor glare. The gentleness of the snow is now

heavy. The distant mountains are lost in flurries and white

fills the picture frame of the window. Our indoor world is

soothing and warm.

I

Today, we are leaving. It is blue skies and dripping

icicles, which at noon the proprietor knocked down with a

broom handle. We walk again over the white road, being

passed by cars, a man on horseback and horse-driven sleighs.

Every few minutes a snowmobile bounces up or down the road.

Taxis without chains and buses with them pass. Downstairs,

when the proprietor counted out the money from the Embassy

representative, he is unsure whether to give a receipt that

American Embassy needs for their records, a paper trail. The

man wants no paper trail for the Georgian government to

follow. This is true all over Georgia, a suspicion of

anything that could be used against them. Small corruption

like this man is showing is a survival technique. It is not

up to Americans to judge as we do not live here all the

time.

April:

Letter from Tbilisi:

It has taken me a while but I have come to the conclusion

that there are two centers of life in Tbilisi. There is

Rustavili Avenue, the six-lane Broadway of this city of 1.6

million people. In terms of many cities in the world, that

does not seem like a lot of individuals living in the same

place but this is a country with a population of 3.5

million. Rustavili Avenue is the tourist center and young

people’s gathering place. All the theaters and most of the

upscale restaurants border its sides. Its main architectural

symbols are the multiple rounded arches and the refuge hotel

behind the statue of King David on the turn-around circle

for traffic. The arches were the Soviet way to signify the

center of commerce. Now the arches houses a restaurant

called Montmarte. The “refuge” hotel is a continual eye sore

for Tbilisi, with the plywood partitions enclosing the

balconies and laundry always hanging from the metal fences

and windows. “Refuge” is not the correct term, although it

is used by visitors and citizens alike to describe the

place. Technically speaking, a refuge is someone who comes

from outside the country and is given asylum. These are

“displaced persons” from northern Georgia where the battle

still wages on who owns that region. The Georgian government

claims Abkhazia as part of Georgia, Abkhazia wants it as

their own country, and Russia says that it is still part of

their empire. Most of the terrorists who plague Tbilisi and

Russia come from this remote mountain region. Also this is

the region where the Russian have been bombing in recent

months in their “war on terrorism”. Russia says that this

northern Georgian region is the haven for Chechen

terrorists. On November 27-28, two Russian military jets

SU-25’s and four assaulting helicopters MI-24 broke into

Georgian air space, pounded the mountain slopes of Pankisi

gorge. Rustavili Avenue is dangerous after dark we are told.

The American Embassy of Georgia put out an alert about a

threat to all Americans in Tbilisi of kidnapping in October

and another alert after a German diplomat was murdered in

December. During the day, this area is alive with citizens,

paying bills at the telephone building, walking the streets

to look in shop windows, buying things from street stays and

of course getting a Big Mac from MacDonald’s main

restaurant.

But after you get to know Tbilisi better, you find that the

heartbeat of business, commerce and shopping is not in this

city center but the other one across the river, Tbilisi’s

largest bazaar. The bazaar is roughly three to four square

miles of open-air stands that sell “everything” from food to

the kitchen sink. I mean literally kitchen sinks, bathrooms,

plumbing supplies, hardware, tape, paint, wire, lumber,

plywood, food and anything else Russians, Turks, English,

Dutch, Georgian, Greeks, Germans, etc. wish to sell. My

driver, and in Tbilisi you must have a driver for protection

as well as transportation, Raphael, takes me to the bazaar

for whatever is needed in our daily lives. We break a

connector on our commode. Go to the bazaar. Need material to

put up an exhibition of art. Go to the bazaar. Need clothes.

Need daily things. Need food. Go to the bazaar. Surrounding

the bazaar, starting early in the morning, are men looking

for work with their signs and tools lined up beside the

road. The bazaar itself is a labyrinth of shops. In fact,

sometimes two or three shops are in the same space and only

when you pay do you understand that it is run by more than

one owner. The walkways are dirt. There is no protection

from the weather. To find what you need, you must take the

time to stop and look at each place, each object for sale,

while walking the winding, narrow passageways. Actually this

bazaar is three bazaars, one for food, one for small objects

and one for construction materials and large items. There

are no signs telling you what is where so you must allow

time to shop. It opens at about ten in the morning and

closes when the sun goes down. It stays open in all kinds of

weather in every season of the year. If you come when it

opens, you can watch merchants shoveling potatoes from the

back of large, enclosed trucks into canvas bags and then

marvel at shoppers who somehow tie on top, on the side, and

cram produce bags inside overloaded cars. They come from

Tbilisi or nearby villages. Whole families come and whole

families sell the wares. It is life at its elemental base

with some luxuries for those with the money to buy.

Merchants know a foreigner by how we shop. We are infrequent

shopper. Three or four times a week, the average citizen

buys at the bazaar. Almost all the time, it is less

expensive than shopping along Rustavili Avenue. Also, there

is little danger because it never stays open at night with

its limited electricity and no bathrooms. But if you listen

carefully as you meander through its maze, you can hear a

heart beating. It is the people’s commercial organ of

Tbilisi.

One thing about living constantly with warnings about

kidnapping, bombings and other dangers, you begin to think

in these terms. As an artist, my problem and talent has

always been that I could imagine all kinds of things and see

the images with crystal clear vision. When the image is a

nightmare, that makes it more difficult to dismissed

(particularly when the event is something triggered by CNN

News on the laptop).

One Drop of Blood

Waking early in the morning, which is the pattern for my

sleep schedule in Tbilisi, I lie a moment, thinking about

the strange dream that still slips in and out of my

consciousness. I was the bureau chief for a national

newspaper, newly positioned, and I sent out a correspondent

to get a story. It gets a little cloudy in terms of the

detail from here on when I try to place myself in the

correspondent’s body. What is clear is the next scene. I am

sitting under a large, gnarled old tree in the courtyard of

a small town in the Middle East and a drop of blood appears

on my hand. As I look up, I see the body of the

correspondent in the limps of the tree. Somehow the person

who killed him placed the body there for us to find. Only

one drop of blood came from the body but it was enough. I

sent off another human being to get a story and he became

the story. Even the murderer knew that. He sent back the

body to tell the world that this is what happens to

Americans who come to this part of the world for stories.

They become the story.

On waking I returned to CNN on my laptop. In Tbilisi,

Georgia, we have no television or radio. In the last eight

days, the electricity has been off each day more than it has

been on so television or radio is not a sure source of

information. And even if we did have electricity, all the

news is in Georgian therefore no television, no radio, just

internet. Shortly after the abduction of Daniel Pearl, the

Wall Street Journal reporter, who was kidnapped in Pakistan,

the US Department of State sent out one of its periodic

warnings to alert all Americans about the danger of

kidnapping. In three months in Georgia, it is the third

warning, with one briefing to go with the printed word. The

message is clear, “Do all that you can to not become a

kidnap victim?”

You wonder at time if those announcements are really for us

or are our government’s way to say, “We told them to be

careful.” In the normal course of events, you make contacts

with individuals in the country where you are staying.

Daniel Pearl came to the Middle East to fill out a story on

the terrorist Richard Reid. He had to make contacts. That is

how one gets a story. He contacted a man named Bashir, who

it was found out later to be Sheikh Omar, a terrorist leader

in Pakistan. The contacts were simple: emails passed back

and forth. One from Bashir read, “I am sorry to have not

replied to you earlier. I was preoccupied with looking after

my wife who has been ill. Please pray for her health.”

Pearl consented to meet Bashir outside a restaurant and he

was kidnapped on January 23. I noticed that the Olympics are

the lead story now on CNN and Pearl is secondary news. Yet

he is still a story in the making. What will propel Pearl

into front page news again is that one drop of blood.

Even the kidnappers know, like my killer in my dream, that

the real story is America’s concept of the value in a single

life. We do hold some truths as self evident. One of them is

that American life and American freedom is precise. Pearl

was not kidnapped as a person but as a valued pawn to play

on some global chessboard.. Yet once he was kidnapped, other

Americans value Daniel Pearl as an individual. If Pearl had

gotten his story about Richard Reid’s connection to al-Queda

and bin Laden, he would have had his reporter’s byline at

the top or bottom of a story. Now it is clear that he is the

story.

We value one drop of American blood. We value human life in

a way that is strange to many in this part of the world. As

I teach American art to Georgians, it is critical to teach

American values and American democracy. The work of art is

only the story when the artist is less famous than his

painting or sculpture or performance. I teach about Texas

artists who become the story when they are seen in the

larger picture of American values.

To live abroad, you are constantly reminded by other

Americans and by the Department of State, “You can become

the story.” But how is anyone know if the person following

you is a terrorist who is targeting you for kidnapping or a

friendly person just interested in improving his English?

Americans cannot conduct daily life abroad in fear and there

has to be some degree of trust. You wish to keep your

humanity alive no matter where you are. Especially after you

learn that a contact has a wife who is ill, has children

that he loves, and wishes to call you, “Friend”. But trust

is difficult and takes time when there is the threat always

of one drop of blood. The problem is, when looking for a

story, time is not a luxury that a reporter has. The bureau

chief wants it while the story is hot.

On way to dismiss nightmares is to stay in bed awake,

snuggling in the warmth when the cold is all around. Also at

times, logic is not the best companion for a Fulbright

Scholar.

Becoming 70 or What’s The Difference Between A Duck?

I woke up considering the fact that I was growing old. I do

not consider it much of the time but tonight I did.

Normally, I wake up about three o’clock and Anne turns on

the light to read. We don’t stay awake long but it happens

as you grow in years. Tonight I said, “I am going to stay in

this warm bed until May and then get up to go dancing with

you for my 70th birthday.” She kind of turned my

way, rolling her eyes to the heavens when I get into one of

these moods, and said, “You have too much to do on your

Fulbright before May.” “No,” I said, “I am going to stay in

bed for weeks on end, just snuggling against your warm

presence. Your skin is so wonderful and fresh.” “Have you

seen the age spots on my hands?” she asked. “No,” I

answered, “you are always YOU to me.” “That’s not logical,”

she replied as she turned a page in her new book. “Logic

does not interest me right now,” I smiled, rolling on my

side. “It is a myth that someone else created, probably

someone in their teens. I feel like asking questions about

the universe tonight like ‘What’s the difference between a

duck?”

Laying there in the warmth, I dismissed the notion that I

would ever have to get up again and began to consider the

uselessness of logic to mature citizens of the world like

myself. Logic was invented for the young. If x happens then

it follows that y will happen. If I make an appointment, I

must keep it at the time and place that it was made. That is

not the thinking or actions in the South Pacific. They get

up when the sun rises or not, and go

to sleep when the moon shines or not. It is the style of

life that we have found in Georgia. As one Georgian said to

me, why should I pay taxes or tell the government what I

make, it is corrupt and will put the money in their own

pocket? I tried to consider this logically but was

frustrated by the fact that the same individual complained

about not having electricity because the government could not afford it in

winter. That is when he mentioned the line about telling the

government about his income.

It is may be logical that to make a living you have to get

up and work. But tonight, in the warmth of this bed, with

the heavy Georgian covers holding off the chill of the

outside cold, it is enough to think about staying here for

weeks on end. It is not logical but it is the moment and it

is enjoyed.

I live in an illogical world, which sometimes borders on

insanity. War has been the prime movement of the 20th

century and the way this century is starting, it is the way

that the next 100 years will precede. During the First World

War (and aren’t all wars events that impact the whole

world), a group of artists, poets, writers and thinkers got

together in Zurich and started the Dadaist Movement of art,

which was based on illogic and was a protest against the

craziness that they saw happening in Europe. They would have

been happy with my question, “What’s the difference between

a duck?” Their answer may have been, “One of its two of its

feet is webbed.” I know that the answer makes no sense. It

is not logical but life is not logical much of the time.

I was born to die. I was born to live. Both of those

statements are true. It is not logical.

Love is not logical. I have had 45 years of a honeymoon

which has never been logical but is filled with love. Should

I run and get a divorce because love is not logical? The

woman that I married so many years ago, that I still enjoy

in the warmth of our bed, is forever “her”, not young, not

old. Art is not logical as a profession. Much of the time

you work and the only rewards are the satisfaction of

finding and exploring something new (many times yourself).

If I were logical, art is not the first pursuit of life. It

is my life though. It is not only a pursuit but a passion.

When people tell me that I “must”, “should”, “consider”,

“be”, “act” something, I want to call out in the loudest

voice possible. It is a voice not held back by age or

infirmity, even when those things are present. I call out,

“Sancho, bring me my sword, my spear and my shield, I just

dreamed the impossible dream. I will stay in bed until I get

up and then ride the winds of adventure. Age be damned.

Logic be damned.”

Another bad wind that keeps us awake, another nightmare

about security is all that the morning brings. Most days are

routine and that makes them safe. Some mornings, it is

important to write out the dream, to objectify it, so that a

normal day can proceed.

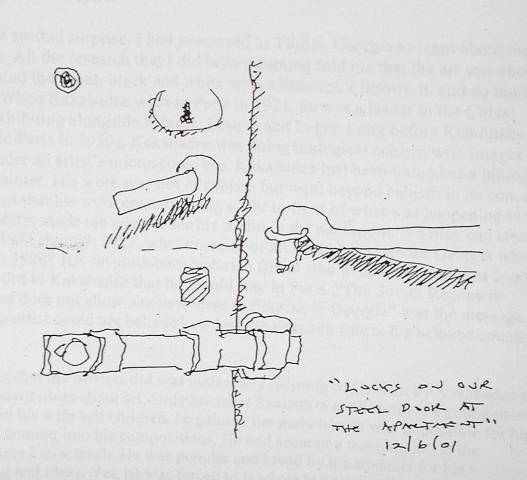

Drown, Swim or Fly

The wind crashes, seeming to lift the tin from the

surrounding garage roofs, rattling old skeletons of memories

that were hidden deep in the subconscious, and furiously

blowing away the last opportunity for sleep. Our second

floor apartment in the heart of Tbilisi, Georgia is at the

center of some demonic wind tunnel, coming in rushes of

sound, attacking the three foot thick walls as if they were

paper. In all this cacophony of sound, nightmares about

security rush in on the winds of the mind. I dreamed of a

scene as if from an Oriental Godfather movie with dark

figures in long coats (seen too many Matrix movies) invading

the apartment as if they though our two steel doors were

only tissue paper protection. I know now as I awake that it

was a nightmare but my artist’s imaging made it crystal

sharp and vivid. Writing is my way to put the demons into

the shadows. As long as we are here and terrorism roams the

world, it will not totally disappear but it also will not

hold me back from completing the job that I cam to do as a

Fulbright Scholar to Georgia. Anne is my lifeline to

normality in a society that is far from my normal. Tonight,

again for the hundredth time, there is no electricity so I

write in the ghostly light of a battery-driven half light.

I know now that I have made a difference in this society and

recently got a letter from Alan Maskin, an architect friend

in Seattle, who told me that Temur Jorjadze, a Georgian

architecd, had followed up upon my contacts and visited the

daylight laboratory at OlsonSundberg Architects. Now, he may

just bring back modern techniques to light this medieval

world of Georgia that is struggling to come into the 20th

century (and hopefully the 21st century). I met

with Ketevan Kintsurashvili, my co-teacher at the Academy,

and discussed the Georgian part of the American Art Archive

Collection.

What made this nightmare so real is the knowledge that it is

all possible (even though I know that it is very

improbable). In my dream, I awoke to several black figures

in the apartment and on my work table where I create the

colors of joy is a severed Oriental head with eyes wide

open, which turns as I walk around it. I can still see it

now awake. That is the curse of a visual photographic memory

that can pull any vision, real or imaginary, up from some

deep place to explore its possibilities in the light. You

cannot control the images that blow in like this wind from

the subconscious. As long as we are in Georgia, we will

never feel completely safe (in fact, that is the tale of any

traveler after the September 11th terrorist

attack in New York) therefore images that are conjured from

the deepest imagination will appear. I have not had this

kind of vivid nightmare since I was a child and now I push

seventy from the lower figures. I know where it comes from

as a mature individual and why it appears but that is little

consolation and it does not make the image disappear. Maybe

I am feeling the pressure of time- so little, so much to

accomplice.

The wind has not stopped as I write in this strange, clouded

light. It blows the demons of the imagination to the

surface, rattles the basic fabric of reality and reminds us

that man and man’s mind is a leaf in a whirlwind of crashing

sound and invisible power. Then again, it just might be a

Harry Potter night of youthful imagination. They call it

“second childhood”, I believe, and the scary parts of the

night wind will blow away with the gentle March winds which

come on Friday. It makes me chuckle at myself to see how

this gift of the imagination can twist a nightmare into a

child’s fairy story and, of course, visa versa.

As I write, my companion, like every night about this time,

5:00 a.m., is Coke and cookies. Maybe I am back into

childhood- so blow wind, the morning sun is coming and your

time is short. I sympathize with your fury! My heart’s mind

reaches out to your measured existence. So blow, blow and

“do not go gentle into that good night”.

The other day at breakfast Anne said to me over bread,

cheese, yogurt and fruit with, of course, our bottled water,

“You are eating dates, raisins, tomatoes and cucumbers which

you have not eaten in our forty-five years of marriage. What

is the difference in Georgia?” After a moment’s reflection,

I told her what could be advice for any Fulbright Scholar

who finds himself a stranger in a strange place, “In the

land of the sea, you drown, swim or fly.” Tonight, I thought

that I might be drowning but this journal kept me afloat,

along with the warmth of Anne’s body beside me.

It is the small intimate things that hold off the rushing

wind and the vivid nightmares. It is these things which seem

so fragile that endure.

What brings you through some days when the language gets

to you, or the traffic, or the lack of schedules, or no

electricity, no gas, no water, and no message from anywhere

telling you why, is the small things. No Fulbright Scholar

can exist without the small wonders that make up some days.

It’s the Small Things that Shape Us

Tbilisi, Georgia: We went out tonight to our favorite

Georgian pizza place. We had three beers, a small bowl of

garlic bread, Capri pizza for me, and pasta with spinach for

Anne, all for $15 USD. As I ate the pizza, enjoying the

olives and the artichokes, I thought about how the small

things in life shape our existence. It is not September 11th,

or the putting together the American Art Collection here as

part of my Fulbright grant, or building the first playground

in Tbilisi with the help of B. Rapoport, or teaching my

classes at the Academy, or the work with the

Non-Governmental Organization’s and the art dealers, or the

chance to paint and show in national exhibitions, or

attending ballets, operas and shows. It is all of that plus

olives and artichokes. I think that I have come to the point

where I am a rock where water is slowly (and in the case of

9/11 quickly) dripping to shape my existence. We cannot

change the shape that we take in a general sense although we

can open new currents of water and the pace of the dripping.

I cannot believe that my shape is predetermined so I fight

against the dripping of the day-to-day and try to shape my

own existence but I know that in one sense my struggle is

futile. Maybe that is why I keep the day-to-day journal. It

records the dripping and the shaping. And in the recording,

the observations, I step outside the action and shape the

inner life. As the king says in The King and I, “It is a

puzzlement.”

While eating an olive and noticing the contrast to the

artichoke, while sitting last night at the opera Carmen and

noticing the contrast of a gargantuan man engulfing the seat

beside Anne and a beauty with an aging man where she seemed

to be elegantly playing her host for this evening, while

tediously cataloging books for the American Art Archive

Collection all day before we went out for dinner, with

having no electricity while writing in my journal, the

water drips and I am shaped. It is the recording, the

noticing, the self-shaping which helps to push the drips one

way or another. Or is all this an illusion? Am I a butterfly

dreaming that I am asleep, or asleep dreaming that I am a

butterfly (as the Chinese query)? If the dripping of daily

events stops, will I awake? It is a puzzlement.

All this is our life in Georgia. It is not the big things

that shape our days but the dripping of daily events that

create the fabric of our lives. Tonight and every night when

our driver Raphael picks us up in his car, he asks, “How are

things, Mr. Joe?” I say, “Fine”, and record that he never

asks Anne the same question. Georgian male life is not water

that will shape me obviously. Anne is one true source of the

water that shapes my living. I shoot her a knowing backward

glance. Always in Georgia, men sit in the front and women

behind. We spend small moments during the day joking about

it.

Today there is no electricity. Last night there was none. In

between we take showers and wash clothes, and then leave to

shop at the grocery store that is below our apartment. They

know us now. We talk of no electricity and winter cold. We

pick up water, coke, Georgian bread, yogurt, six nut cakes,

toilet paper (we are looked at strangely because I buy three

roles everyday since I use them to clean my paint brushes),

one Snicker bar, two soups, and Russian breath mints. We are

normally together and the young girl says, “Hello”, in

English, and we reply in Georgian. It is a ritual of daily

life that we and they expect. On days when I just run down

to get something, the girl asks: “Where is your wife?” The

two of us are joined in her mind and therefore in ours too.

The lady behind the cake counter always tries to sell me

some new sweet. It is a game we play where I refuse most of

the time with a wave of my hand, a knowing smile and a head

shake as both of us do not speak the other’s language. Each

time I come she still asks and on rare days I say, “Yes”

(“Ki” in Georgian). It keeps the ritual alive and the drips

of living continue.

Just as the outside of our being is shaped by daily sun,

wind, stress and laughter, the inner self is shaped by the

dripping of large and small ideas, emotions and sensory

experiences. The mind does not separate size when ideas or

feelings are concerned. It is not time that ages our being

but the dripping of events, some real, some not, like olives

and artichokes in a sea of pizza.

An artist is lucky as a Fulbright Scholar, he has learned

how to forget. I wrote this article in celebration of that

gift, the importance of forgetting.

The Important Of Forgetting

Being far away from your home country, in a land where the

language is strange even in the world of languages since

Georgian is one of the fourteen world languages but is only

used in Georgia, you think and read a lot. Recently on

reading again a 1976 publication by Edward T. Hall, called

Beyond Culture, I was reminded of the artist’s, the

creator’s need to forget. Children learn it as they play.

You purposely forget so that you can see the world with

fresh eyes. Hall’s says, “The failure to understand the

significance of play in maturing human beings has had

incalculable consequences, because play is not only crucial

to learning but (unlike other drives) is its own reward.”

To an artist, forgetting is critical to any pursuit. I have

the kind of mind that can remember brushstrokes as I walk

through a museum exhibition. It gets in the way when I pick

up a brush for a new painting. Therefore the first hour or

so of painting is to forget all those other painter’s

solutions in my mind’s eye. This allows me, or any creative

person, to come to material with fresh eyes. The poet,

dancer, writer, musician, inventor or learner can find

individual and new solutions to “stuff” that others have

only seen through established patterns or forms. The Russian

scientist Luria in the mid 20th century

established the importance of forgetting in his book The

Mind of a Mnemonist, the life story of a man who could not

forget anything and remember everything that was placed

before him. On first sight this would seem a blessing but on

closer look, the man was a mental cripple. If you gave this

man a problem to solve, as a visualizer he could solve it.

But he could not understand poetry and abstract ideas.

“Infinity” and “nothing” were beyond his mental grasp.

I remember in school when the teachers would reward the

students who could memorize the best. I could not. It took

me years to find ways to keep things in my mind. I was

always seeing the world with fresh eyes and drawing/painting

it with those visions. I finally learned that if I put a

context to the data that I could remember it and by taking

away the context forget it as easily. This has practical

implications. At one point in my life I build houses from

the ground up. I did five over the years, from the

architectural plan to the last nail or the trawl of

concrete. After the first house, I found that I had to

forget all the bad things that happened, all the aching

muscles and long hours, all the feelings of disappointment

when something did not come out as I planned before I could

start a new project. Since I am a visualizer who remembered

pictures of things placed in front of me, I had to learn to

forget them so they did not get in the way when I wanted to

have a new vision.

I found that it helps to know how the brain works and that

there are ways to help you forget. Japanese Zen monks repeat

a phrase until the words are lost and only the sound

resonated in the soul of the priest. As Hall says, “The

reason man does not experience his true cultural self is

that until he experiences another self as valid, he has

little basis for validating his own self.” At points in my

life I travel to find my other self, to forget the Western

man that could only see with Western eyes. In the West, we

place logic and irrationality at two opposing poles. Recent

mind studies find that they are positioned in the same place

in the brain. Irrationality is a way to start the process

toward logic and visa versa. In the front of the brain are

the faculties for perception, body movement, performance of

planned action, memorizing, and problem solving. If you

dance, it helps with problem solving or your performance of

a planned action. You can memorize better if you clear the

mind of old “stuff” that clutters up the corners. Forgetting

is essential to creativity. It is too bad that the warring

factions in the Middle East never learned that lesson. In

the long run for a human to enjoy the freshness of spring, a

new rain, another sun-filled day, your child’s small hand is

yours, love and sex, forgetting is as important as

remembering.