|

American Supra: Book Five

Turning Back To See

Let your boat of life be

light, packed with only what you need- a homely home and

simple pleasures, one or two friends, worth of name, someone

to love and someone to love you, a cat, a dog…,enough to eat

and enough to wear, and a little more than enough to drink:

for thirst is a dangerous thing.

Jerome Klapka Jerome,

1859-1927, from Three Men in a Boat (1889)

‘Tis distance lends

enchantment to the view,

And robes the mountain in

its azure hue.

Thomas Campbell,

1777-1844, from Pleasures of Hope

A Woman is a foreign

land,

Of which, though there he

settle young,

A man will ne’er quite

understand

The customs, politics,

and tongue.

Coventry Patmore,

1823-1896, from Woman

Life is an end in itself,

and the only question as to whether it is worth living is

whether you have enough of it. Oliver Wendell Holmes,

Jr., 1841-1935, from John Marshall (1901)

What is life? A madness.

What is life? An illusion, a shadow, a story. And the

greatest good is little enough: for all life is a dream, and

dreams themselves are only dreams…. But whether it be dream

or truth, to do well is what matters. If it be truth, for

truth’s sake. If not, then to gain friends for the time when

we awaken.

Pedro Calderon De La

Barca, 1600-1681, from Life is a Dream

Father, dear father, come

home with me now,

The clock in the belfry

strikes one;

You said you were coming

right home from the shop

As soon as your day’s

work was done.

Henry Clay Work,

1832-1884, from Come Home, Father (1864)

A man travels the world

over in search of what he needs and returns home to find it.

George Moore, 1852-1933,

from The Brook Kerith (1916)

Tbilisi 8

The covers keep us warm. We snuggle close to use our body

heat to ward off the cold. Certainly the walls and the

windows do not. The walls hold the night’s cold and the

windows are fragile interference for the harsh winter winds

that drop the temperature each night, each morning, each

day. I go to the Academy when I teach and it is cold. I go

to the National State Museum to view the works of art by a

sliver of daylight from the covered windows and it is

freezing inside so that we do not stay long. This morning,

although the bathroom calls, we stay a little longer under

the covers. There has been no gas for a week, therefore no

heat and no cooking. As we summon our resolve to meet the

day and the practical matter of using the bathroom becomes

more pressing, we move, get up quickly to dress in the

multiple layers of cloths that are only a partial deterrent

to the cold. The lights go out as if throwing another

challenge to living in Georgia before us. We also have had

infrequent electricity since we came back to Tbilisi in late

January. Anne jokes, “Maybe we should go back to bed.” For a

moment, we consider this wild idea and then reject it with

pleasant thoughts. We turn to the job at hand, battling the

cold. When the temperature is low in the apartment, the

freezing attacks the body but more it attacks the spirit. It

is hard to have lofty thoughts when your limbs are beginning

to numb It is just too damn cold. We have endured it for two

months; Georgians have endured it each winter for eleven

years. In May, we will be leaving all our winter clothes

with friends who are staying. Many cannot afford to fly away

from the cold that blows from the Caucasus. America and

Russia has a “cold war” for years but they had no idea of

this kind of indoor weather. Yesterday, Parliament (who does

noting to help with the problem, in fact these five days

were caused because the government did not pay a Russian gas

company) announced that it was “Women’s day” and all the

shops were filled with flowers. It was beautiful, although a

rebirth of a day that the Communists started. I suspect,

though, that it really was some camouflage for their

inaction in holding off the cold. Raphael, our driver, tells

us about how the television says, “Today it will go on.” For

the fourth and fifth day, it is a lie. There is no gas.

There is no electricity. There was no water all night. My

room for painting, which had been the warmest with the gas

heater, is cold and unused. It is hard to celebrate the

colors of life when your fingers are blue and chilled to the

bone. And the Georgia wind does its job to find each crack,

each defense against the numbing frozen march of air. It

blows the useless television disc outside the living room

window, the roofs of tin on the garages below containing all

the BMWs and Mercedes, and it blows away initiative if you

let it. Therefore, I write to warm my limbs. I write and

draw to keep alive the creative spirit which is the heat of

my life. I write because passion can be warmed by the inner

body heat. And lastly, I write while I seriously considering

going back to the warmth of our bed.

A Georgian painter friend complained the other day about her

daughter’s minor operation, which was in actuality not so

minor. Her daughter has lived in America for a time and has

gone to doctors there. Any procedure was explained in detail

before any “minor surgery” was performed. Here, she says,

she is told nothing by the doctor in charge. That was the

style during Communist times but it was to change when

democracy came to power. Obviously, it has not. The friend’s

daughter is very upset because she feels that it is more

than just doctors not telling patients what they are doing.

It is a human rights issue. I think that she might be right.

We have no gas for days and no one, in any way, television

or by public announcement, tells the people “why”! Oh, they

play the domino excuses. “It is not our fault. It is the

Russians. It is the City of Tbilisi. It is someone else than

us.” Raphael relates to us what he gets from the television

but mostly it is propaganda and inaccurate (everyday is the

day that it will come on). They promise and do not deliver.

No explanations.

The electricity came on at 10:00 a.m. after three hours,

while businesses downstairs have to use more expensive

kerosene, but now we have our electric heater on. I notice

the pattern of the outages. It is always during business

hours so that the stores have to use their generators run by

kerosene. I ask, “Who sells the kerosene?” Another Georgian

friend answers, “Mafia.” Whether it is true or not, there is

no trust in the government, its announcement or its

promises. Now, we huddle in the small computer room which

can take the chill out of the air. The rest of the apartment

is still freezing. In Georgia, you count your small

blessings and wait.

As the end of my Fulbright Scholar’s nine months comes to an

end, I begin to compare the two cultures, Georgia and

America. The major differences, beyond size and living

style, are three that I see: 1) the system (only one, and

not really that, of the cornerstones of democracy are in

place in Georgia- education of the elite to lead), 2) human

rights (women, citizens, minorities, etc. are not honored in

practice although they are in rhetoric), and 3) America’s

problems with the elemental comforts of life are the

exception; in Georgia, they are the role. The latter

situation leads to no planning, no scheduling, no

initiative. There are no or little human rights honored in

practice which leads to distrust of any governmental agency

or individual who wishes to make politics his or her

profession. The first difference that I mention, the system,

is a major problem to becoming a full partner in freedom and

peace. I have come to love Georgia and her people. In a

family setting, they are a most generous people. They take

you to the womb of their heart. Although this is a male

dominated culture, I still see it as a “she” not a “he”

culture. In truth, the women may be one of the dominant

forces in bringing Georgia into the 21st century

and to a true free democracy. The Georgian love of art

(visual, performing and literary) is an asset to growth but

it must be wedded to a political system which can be

trusted; one which gives more than it takes.

Tbilisi 9:

I have a new story about David Kakabadze. He hated Socialist

Realism but was force to do it to survive under the Soviet

iron control. He also wanted his Cubist adaptations of

Socialist Realism to be seen by the public, therefore he

painted a landscape filled with cones, cubes and cylinders

and in front of them, at the edge of the mountain, he placed

three billboards with images of Lenin, Stalin and Beria (the

latter two from Georgia). The museum was forced to hang his

Cubist work with other works from that time. Who could

reject Lenin, Stalin and Beria? When Stalin and Beria were

out of favor with the new Soviet leader who came to visit,

the museum was then forced to paint black over their

portraits, but it still left Lenin in front of the grand

landscape. It pleases me to see the ingenuity of this artist

who fought to the last to get out his ideas.

Something happened yesterday and I still do not know what. I

stopped feeling that “I have too much to do in too short a

time”. It just stopped and I cannot explain why. I made some

decisions three days ago about priorities, writing them out

in a formal order but that does not explain the joy, the

buoyancy of my attitude. I am a renewed person, suddenly not

tired, no old, not overworked, and I have not stopped my

jobs, got ride of any commitments or slackened my pace on my

painting. I have completed two large paintings, and spent a

day at home in the apartment simply with Anne, gone to a

simple but enjoyable dinner for two of chicken, been, fried

potatoes and a piece of cake, snuggled early into bed, and

got up as usual early in the morning to write and think.

Nothing has changed and yet it is a new world, a new

beginning. I still cannot explain it and will not try. It

just feels good to believe that “I have all the time that I

need to do what I wish to do.” As my daughter, Samantha,

says, “Dad, you are weird.”

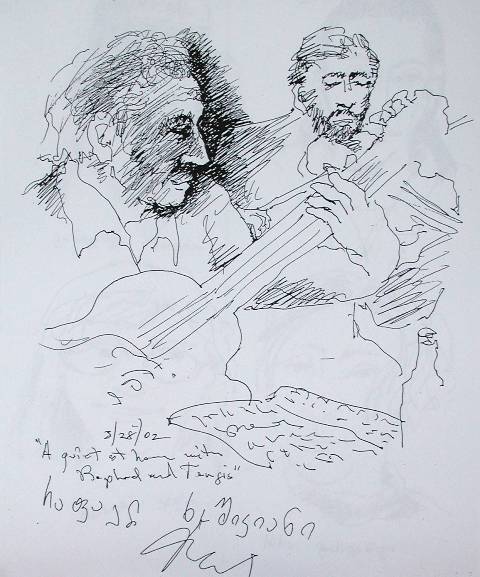

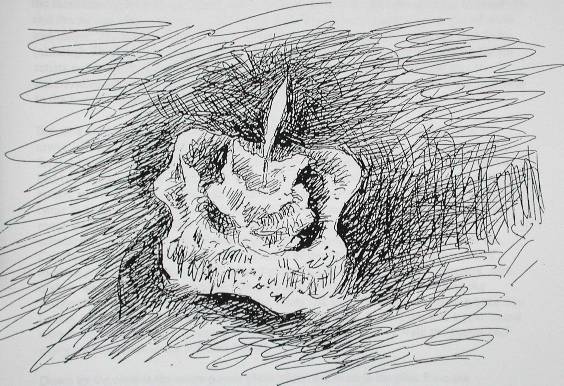

I have not honored my lone lighted friend before so here he

is. I think of gender with this candle because of the limp

lean of his stature. It was more pronounce when I first used

him for light but each night as his wax softens I made the

attempt to straighten him but there is always some lean. He

must be an old candle light, like me, which will never again

be perfectly straight but still gives off as much light as

the newly-bought, young candles newly-formed and dipped. We

bought this one in Kutaisi and as Anne says, “We may need to

buy some more before we leave in late May.” It is a few

dwindling days, but who is counting?

The stillness is broken by the lone dog calling to some

unknown, unseen mate who yelps replies in irregular patterns

of sound- at least, irregular to my untrained ear. In my

last days here, I will work with the State Conservatory on a

plan for major improvements. As the Rector, Manana, says:

“Our situation is terrible and the building is a national

treasure.” Since Anne and I have had nine months of pure joy

at the Opera House listening and watching the graduates of

the Conservatory, this is the least that I can do to repay

their efforts and excellence. Also, by going to the

Conservatory each week, maybe my ear will be trained to same

degree that my eye has acquired. Sound is the one thing that

they have in abundance. Now, though, outside, the rain has a

pattern that I cannot read with any context.

It has been raining steadily since early evening last night

and now it is just a sound in the night to go with the other

creaks, groans, and splashes. The day is waking- the

building stirs. Cars are now heard in the distance. The wind

picks up so the metronome of irregular beats comes again

into the silence. A dog backs and fades. I need to give my

lighted friend a rest, clean up the oilcloth that covers my

desk, and snuggle again against the security and warmth of

Anne.

Days are for others and projects but the night is my time. I

wake again early and sit in the darkness listening and

thinking. Now, the barking is from a pack of dogs. It

punctuates the physicalness of the silence and momentary

hiss of a passing car. Anne found a second candle. It is the

same size as my lone friend, and now I sit in the living

room, again at the oilcloth covered table, reading and

writing. What surprises me still, even after 45 years of

marriage, is that I am still filled with the love that first

drew us together, but now it is richer and deeper, adding

years to the mix and knowing that what we share will last in

our children. But we will burn out like my two candle

friends. With the power outages, I read more and write more,

not being able to work at the computer. It is part of the

process of survival. I cannot dwell on the aches and pains

of growing old. You ignore what you can and endure what you

cannot. There is little time for thinking about the vehicle

needing repairs since life is precious and time for thinking

must be things that uplift the spirit, not push it into

thinking “old”. At some point, the body will affect the mind

but I will fight this “wearing out” process to the end. As I

said to a friend, “Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage, against the dying of the light.” I do ramble on

but that is part of the Georgian experience.

20/20 Vision:

The year is 2020. Karaman Kutateladze walks the land again

where his vision started so many years ago but it has

changed so dramatically in the last 18 years that even he is

surprised at what Garigula’s Art Villa has become. It seems

only yesterday that the Foundation of the Revival and

Development of the Cultural Heritage of Shida Kartli was

created in 2000. Now, it is the idea and training center for

artists in the Caucasus Region, located in Shida Kartli but

moving out to the edges of the world. He had talked of this

vision with his wife Ana and other social activists in the

late 1990s. He had known the villa as a boy when his father,

who founded the Tbilisi Art Academy, had spent summers in

Gargula. It was always that “lovely 19th century

house in the vineyards with the tower, called the Bolgarsky

Citadel”. It was not until the year 2000 that the vision

started to materialize when the Georgian Ministry of Culture

awarded the Foundation, a group of visionaries, headed by

him and supported by two architects, Dima Mamatsashvili and

Irachi Vacheishvili, the house and the grounds for an Art

Villa.

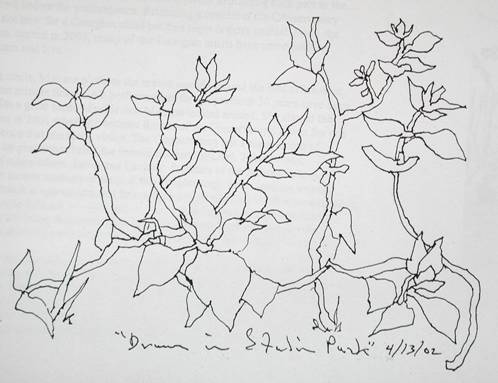

As he looks around, the white blossoms were coming out and

the green/brown vineyards still give abundant grapes for

wine. This is a region known for its wine and its healthy

climate. Pilgrimages by Georgians to Garikula have been

going on for years because of the medicinal quality of the

spring water. In fact, myth states that the sunlight in

Garikula and the air can stop nose bleeds and help

intestinal problems. Garikula is a mix of myth and magic.

The magic comes from the townspeople and the artist

population. Garikuka (although 75 kilometers from Georgia’s

capitol, Tbilisi) has a history as a retreat for the artists

and artisans of the Caucasus. The original mission of the

Foundation was to decentralize culture in Georgia. Little

did they imagine that it would reach out at this time to the

corners of the world?

But now walking down the road which leads to the splendid,

renovated Art Villa, its tower still standing majestically

tall with the two wings of the house restored to their

former beauty like arms open to greet all visitors, Karaman

remembers the shape that it had been in when the vision

began. The walls, floors, balconies, ceilings, wine cellar,

ice house, and everything needed a face life and more, a

reconstruction. Students and artists came to help,

architects donated time, some painting and mural making was

done, but more was needed. Now, that work is completed. New,

young students, some on scholarship (supported by the

Foundation’s endowment), from academies all over the

Caucasus region (and around the world) know of the Art

Villa, its invited masters of modern art and its

international faculty of painters, craftsmen, sculptors,

designers, film makers and other media specialists. On each

side of the road that winds around the Bolgarsky Citadel is

the workplaces of the artists and artisans. It is like

stepping back into history and forward to the future at the

same time. Garikula, in the past, was a year-round retreat

for artists but now it brings tourists to the small hotel.

They walk the streets and enjoy performances in the 200 seat

theater.

Down by the river is the water-power plant which had been in

the plan from the beginning, giving electricity to each shop

and the Citadel (while saving money to operate the Art

Villa), but that is not all. To the right stand three

windmills where only one was planned in 2002 and on each

house are solar panels which use the abundance of sunlight

in the valley. Most of the food for the Art Villa is still

grown on the 25 thousand square meters of land. Anyone who

has tasted Georgian food knows that it’s fame. Karaman says

hello to the potter from Japan, the printmaker from America,

the Germany painter and of course all the Georgian artists

and craftsmen who have come back to Georgia to be part of

the Garikula Art Villa success story.

Tonight there will be another grand opening of art works

from the summer students and faculty. Because of the weather

in the summer months with cool, refreshing breezes off the

Tezami River and the circle of rounded mountains protecting

this special place, the town is filled with international

tourists. New businesses are appearing each day. Karo, as

his friends call him, cannot keep up with the growth in the

small town or the Shida Kartli region.

With a broad smile, he thinks about how his father wanted an

Academy in Tbilisi to train artists in the early 20th

century, and now this vision of the Art Villa, realized in

Garikula, will train artists for the 21st century

and beyond. Standing at the entrance to the artist’s street

which had been a dim dream in 2002, he thinks: “Socrates was

correct. ‘Education is the fuel of the mind’ and art is the

flame that sets that mind and spirit ablaze.” The Garikula

Art Villa is alive and ablaze with creativity on this late

summer afternoon, one of many in the history of a vision.

Vision: 2021.

Imagine. The year is 2021. Exactly 120 years from the time

when the Conservatory building was built, 103 years since

the Tbilisi State Conservatory was registered as the first

music school in the Caucasus, 30 years since Georgia won its

fight to become a democracy, and 20 years since the great

renovation project of 2001 was conceived. The grand old,

repaired structure is showing off its glory for this special

night. Professor Manana Doidjashvili, winner of many

international piano competitions, retired Rector of the

Conservatory, and tonight grandmother, is attending another

world- renowned artist’s concert but this time with her

granddaughter and this time the artist is Georgian,

returning home. As she looks around with pleasure in seeing

the Concert Hall dressed in her best neo-classical clothes,

she thinks: “Every one hundred and twenty year old needs

some time in the repair shop to keep fit and young looking,

with a tinge of age to add distinction”. The little girl

comments on the new gold on the decorations, sparkling with

tiny beams of light from the magnificent chandelier placed

there in the renovation of 1997. As they enter the great

Concert Hall, opened in 1943, the girl’s eyes became wide as

she snuggled into her soft, blue seat. Like all Georgian

children, this is a known ritual which begins at the age of

two or three. In the beginning ten years when Georgian

democracy was growing up, the little girl’s mother had

attended with Manana each week for the opera, chamber,

individual and folk music concerts. At the Opera House, down

the street, she had watched and listened to adult ballet,

symphony, and opera, plus children’s performances at Sunday

noon, with a storyteller explaining each part to the

overflowing crowd before the performance. Attending a

concert at the Conservatory Concert Hall is not new for a

Georgian child but this night is extra special. Since the

Great Renovation started in 2001, many of the Georgian

artists have come back to Georgia to perform and live.

With a knowing smile, Manana pictures the crowd outside

around the box office door, hoping to buy last minute

tickets. All performances for the previous 30 years have

been sold out. It is with a great sense of pride that Manana

looked around. She started the Great Renovation in 2001 when

she became Rector of the Conservatory. It was for this

family of excellence that she had a vision. The Conservatory

has a track record of excellence with its professors being

the former students of Liszt, Tchaikovsky, Venieavsky, and

many others. Lavin and Lavinia, founders of the Julliard

School of Music, sent their former students to teach at the

Conservatory. Now, looking around, Manana thinks that it is

appropriate that this unique school of music is often

mentioned in the same sentence as Julliard, ---------, and

--------- when the great world centers of musical learning

are being discussed. Now in 2021, students from everywhere

are attending classes at the Conservatory. “It is like a

musical United Nations,” she thinks.

Before the major improvements to the Concert Hall in 1997,

she remembered walls falling apart and rats running the

halls instead of the crowds that now congregate around the

entrance door. Before the great renovation project began in

2001-2002, equipment had worn out, walls were peeling and

cracked, the foundation of the building was in standing

water, and no room had sound-proofing on the doors. Now it

is well lighted, safe, repaired when needed, and continues

to have a successful, energized family of musicians (that

is, beginning students and seasoned professionals). “Yes”,

she thinks, “It has always been a family of excellence but

now it not just a Georgian secret. Now, the entire world

knows that George Balanchine (Balanchidaze) and others was

Georgian. Now everyone speaks of the Tbilisi State

Conservatory in the same breath as any great, world music

center deserves. And now in 2021, all the George Balanchines

have come home to teach and perform.”

A young man walks on stage after a triumphal tour in

thirteen nations and sits at the newly-purchased Steinway

piano. The audience’s sound hushes to a knowledgeable

silence. A breath is taken. A vision of the music passes

through everyone’s mind. The hands slowly raise, and then

strongly strike a note that fills the hall with renewed

glory, and another chapter in excellence opens at

Saradaishvili Tbilisi State Conservatory.

Tbilisi 10

A lone dog barks. It is a welcomed sound unlike the vicious

sound of late last night. That was obviously a short but

violent dogfight. It woke both of us until the silence was

restored. When we arose and began to go out the front

entrance of the apartment house, a large dead dog lay across

the opening. We went to shop out the back entrance. On

returning, Anne noticed a smaller dog with her head on the

body of the dead one. It moved Anne deeply. For me, it was

symbolic of life here- on the edge of survival. It was only

later in the day when we went out for shopping again that we

observed that the body had been adjusted several times so

tenants could pass. We never went that way all day and when

we returned from the Embassy, the dead carcass was gone.

Later when we walked to pick up fresh, hot bread, we looked

into the large containers for garbage but the dead body was

not there. And now, except for the lone dog barking in the

early dark of morning, the image is fading. Survival demands

thoughts of living, not lingering on the dead.

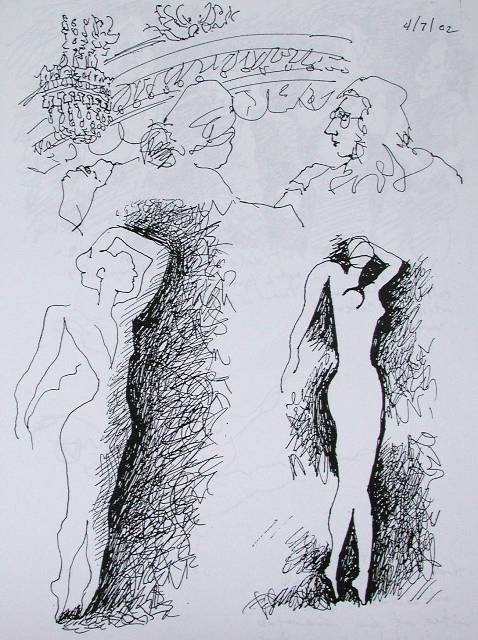

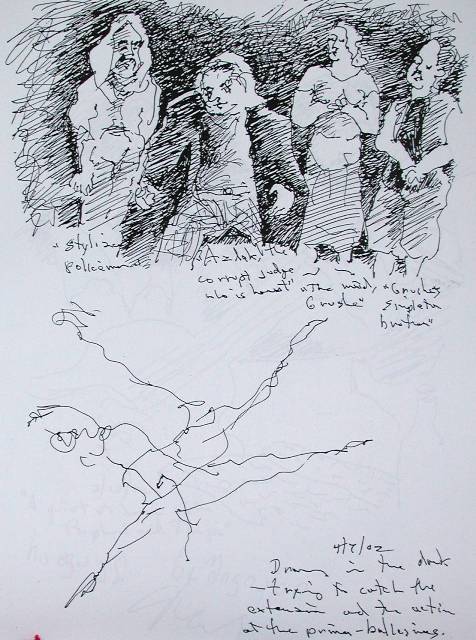

It is another day of magnificent ballet and farce. The one

image that remains is the one line of a dancer’s trained

body- one gesture where a figure stands on tiptoes and seems

to fly. Isn’t that what all artists do- help us to stand on

our tiptoes and imagine flying in grace and eternal beauty?

It is one line against the chaos of an image of lines. It is

one trained line of beauty that stands against the darkness.

This morning another candle burned to extinction and a much,

much taller one was placed on top of its still hot wax. The

tall one is about fourteen inches in height, standing beside

the last of the Kutaisi candles that is now down to its last

few inches of service.

As always, we went to a concert at the Conservatory where we

did not know who was playing or what the program contained.

Much, much later we learned that the piano concert was by

Jan Claude Petie from France. He played Shubert, DeBussey,

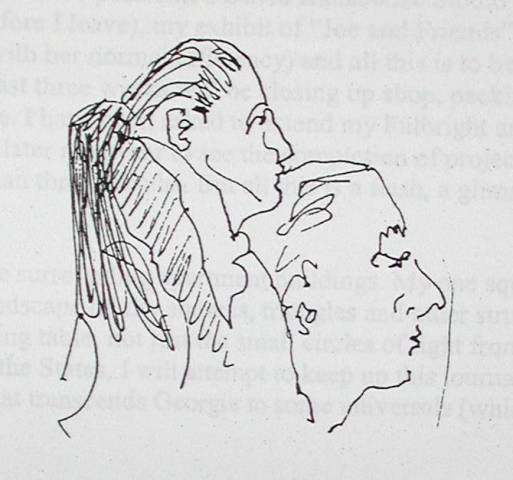

Ravel and Debrie. During the first two numbers, I noticed a

man intently listening to every note with his eyes closed. I

singled him out of the audience to draw. It was only at the

first intermission that I learned the reason for this

special listening. He tuned the piano. His ear, unlike mine,

heard the soft and hard edges to all the shades of sound,

plus the nuances in between. A woman in a red sweater nudged

by my seat and left a thin red thread on the back of the

green seat before me. I was torn between reestablishing the

purity of the field of green and leaving the thread as an

accent to heighten the green. Why is it that I see all the

little things that others might miss? It has been my life to

see the small reds on a field of green.

The sound trickles over us like rivulets of water or crashes

upon the shores of our inner souls. One piano, one player,

one audience and it is all one. The waves of sound rise up

and bring us tenderly back to the earth of our emotions.

Just as the eye can stir our emotions so the notes in the

grand concert hall play upon our heartbeats and nervous

system. For a time, we are the music. All through the

performance, I observe a weathered face of a woman who lives

each note, leaning forward, her arm upon the seat in front

and her intensity taking her someplace else.

I learned a new superlative today. The word is “vishi”. I

believe that it is Russian for “beyond superb”. It is a word

to use with the appropriate hand movements and positioning.

It is said with a low, guttural sound and extended into time

and space.

In a few days, this adventure as a Fulbright Scholar in

Georgia will be over and we will fly to Beijing, stay a few

days, and then back to Texas- home. I am sure that many of

my friends will expect me to be the man that I was before I

left, returning to the routine of the Southwest (and I may

to a degree). What they will not see, or really understand

because I do not understand it completely, is that I am not

the same man who came to Georgia last summer, journeying to

Kutaisi to be part of an international artist’s symposium,

returning to Tbilisi to teach, paint, write and lecture on

American art and architecture, and help a few individuals

and institutions to learn the survival game of free

enterprise. Somewhere, just under the newly-sewn, gift vest

with Georgian designs is a younger man, dressed as my

now-Georgian, imaginary ancestor. He looks something like

this:

There is silence that goes beyond normal where even the

creaking of this old concrete building is a welcomed sound.

I know that it is impossible for concrete to “creak” but

there is that sound that dismisses the impossibility of the

event. A gentle wind adjusts the tin roofs but only a quiet

sound in the absence of any other sounds. Somewhere in the

kitcheon, something keeps a metronome kind of measured beat

but not a disturbing sound, a kind of soothing remembrance

of our timed existence. There is no electricity again so I

write by the light of two candles. At one time in my life,

this would have seemed romantic but now it is just

inconvenient. Anne stays in the warming comfort of the bed

but I was getting too warm and the solace of sleep is not

possible when the mind is alive with ideas. Now, I am not

warm at all. One light, probably run by battery power, is

lit high up in the darkness, like a square star in the

approaching morning sky. It is interesting with candles that

as they burn they give off more light, using more wicks to

burn. The morning sky now is a dull dark gray with a whisper

of blue. Silhouettes of the apartment buildings come to life

and a tower of red dots projects itself into the dawning

sky. The wind picks up and the metronome becomes more of a

hurrying beat. My mind says, “It is an antenna somewhere

hitting the building, blown by the wind” but this logic does

not register, only the bar sound striking the impenetrable

apartment building.

Saturday, I had class again, two students and two faculty

members. The Academy does nothing to advertise my lectures,

and no one comes to open the room that I was using in the

first semester. Anne gets discouraged. I do not have the

time or luxury of that emotion, having too much to do in too

little time left before we leave Georgia. I will, though,

create a poster to get out the word on my Saturday lectures

and see if that will help.

Now the single square of light is spotlighted against a

large minimal square of black/gray. There is a painting

there somewhere, I think, storing the image.

It is now only 67 days before we board the airplane to

Beijing and then home. I find it hard to look ahead more

than a week at a time and those weeks are streaking by with

a speed that surprises me. The Kagle Resource Room for the

American Art and Architecture (a name that I first protested

but not loudly or prolonged), the playground (which Lika has

taken over with a passion), a David Kakabadze Studio

Foundation (which must be created before I leave), my

exhibit of “Joe and Friends” (which is taken over by Nino

Zaalishvili with her normal efficiency) and all this is to

be accomplished in the next five weeks. The last three weeks

will be closing up shop, packing and getting ready for the

journey home. I have been asked to extend my Fulbright and I

decided that, if asked, I will come back later next year to

see the completion of projects that do not get completed,

but no more than three months. But all this is a flash, a

glimmer of a future decision, reality is NOW.

Definition is coming to the surrounding apartment buildings.

My one square of light slips back into the emerging

landscape of city squares, triangles and other structures. I

am beginning to see my painting table, not just the small

circles of light from the two candles. When I return to the

States, I will attempt to keep up this journal but here it

has been a lifeline to reality that transcends Georgia to

some universals (which also transcend America). I see

Georgia as a surreal landscape at times. Time here is like

the Dali painting of dripping watches. In Tbilisi, citizens

do all that they can to survive and push away the reality of

their bare existence, no pay for hard work, and constant

unintelligible shortages of basic needs like electricity,

water and gas. Tbilisi motorists drive too fast, have no

road etiquette (except push in front, go first), nudge

bumpers into line without waiting for their turn, seeming to

rush everywhere but have nowhere to go except survival.

Magritte painted this world of faceless people in a

measured, ordered, stagnant,

perpetually-in-motion-with-no-destination world. And yet, at

home with their families or at the Opera House with their

children, one sees a different face to Georgia, generous,

purposeful and beauty-seeking. In business life, all too

often, planning is a myth. Many feel that Americans have

silver and gold pockets for the asking, deep and unending.

The concept that I have tried to teach of “to get, you have

to give something of value” is difficult for Georgians to

fathom and “in kind” contributions matching hard cash for

grants is a painful lesson, not easily learned. It appears

that no one values their time, because the time that people

work is not valued in salary amounts commensurate with their

labor, energy or effort. Therefore to put a value on life

and work to match someone else’s grant money is not apparent

to a Georgian. As I said many times, life here is hard.

We are driven to the Opera House to see the ballet, give our

tickets and are told that they are for last week’s

performance (although when we bought them, we were told that

last week’s ballet was sold out but they had tickets for

this week’s special event). Standing in front of the small

caged window, I complain that I was given the wrong tickets.

A student of mine from the Academy helps to translate and we

are told to go to the person in charge upstairs, inside the

Opera House. When we get there, we are ushered to our box

seats as if nothing had happened. It seems that when tickets

are printed they run out, so any ticket is given to

Americans to use. Somehow, magically, all at once, the

tickets are for this week. Georgia is not like anyplace in

the world that I have traveled. You do have to accept

surrealism everyday as a way of life. It seems to work.

As I stood at the ticket counter, a large woman tried to

edge her way in front of me, although she could see that I

was being waited upon. Since I am also large, she didn’t get

in front of me but I had to bodily make it clear that this

would not happen. There is no concept of “waiting your

turn”. There is no turn. For me, it shows a lack of

understanding of human, individual rights. Life here is a

collective pushing in front of the line. Again, the contrast

is vast. The ballet is marvelous. I have used that word

“marvelous” too often but I have tried to find another word

and just “marvelous” fits. The ballet dancers are

professional, acrobatic and superb. The audience is one of

the best that any society can boast for in their

understanding, appreciation and loyalty. The box where we

are seated has an older prima ballerina sitting in front of

us. It is refreshing to watch her on center stage at each

intermission. Going to the ballet today has been the worse

and the best experience.

June:

Letter from Tbilisi: As our year in Georgia comes to

an end and my Fulbright work is over, images spring to life

before my mind’s eye in a clear and sometimes fuzzy

panorama. Georgia is like the Roman god Janus, the keeper of

doors and gates, who was honored as the god of beginnings

(in fact, we name our first month of the year after him).

His Roman name was “Ianuarmius” which is close to our word

January. He was honored because “one must emerge through a

gate or door before entering a new place.” Certainly,

Georgia is a new place which has traditions which stretch

back 3500 years. Janus was the god with two faces.

Walking the streets in Tbilisi, one sees enormous poverty.

Beggars everywhere with a hand out, mothers with rag doll

babies in their limp arms, haggard old people, talented

musicians, and little children who follow you down the

street tugging at your clothes. If you try to cross

Rustevili Avenue, you take your life in your hands. You

daily see the most inconsiderate drivers in the world speed

up when a pedestrian is in sight. I watched a man on a small

side street getting knocked down by a Mercedes (or it might

have been a BMW) and saw the driver yell at the man for

injuring his shiny car. It seems that drivers take the years

of frustration of no electricity, no gas, no water for long

periods at unscheduled times out on the gas pedal. There is

no road etiquette. Double center lines are ignored, one way

streets are just a challenge to overcome by backing up or

driving in the wrong direction, and red lights are

occasionally obeyed. Everyone drives as if their life

depended on the speed that they could obtain on the short

stretches of narrow streets whereas the truth is the

pedestrian’s life is the one at stake.

And yet in the home, as a guest, you are honored as no guest

is honored anywhere in the world. As one friend said in

Kutaisi, “Georgia has survived the oppression of Mongols,

Turks, Persian, and Communists because at our table we honor

all guests, even our enemies. We greet them with wine, food

and an honored place at the table. In fact, at the Georgian

table, a plate is always left empty for the guest who might

come.” My students carried my bags to class. They came to

lectures when the inside of the building was freezing more

than the outside because the three-foot thick walls retained

the night’s cold and held it for the day. I told them, “If

you come, I will teach and we will freeze together.”

Georgian hospitality is legendary and goes back for

thousands of years. It is one of the tools of their survival

as a people, a culture and a unique civilization. But then,

since democracy and freedom came in 1991, their institutions

are impersonal. The hospitality of the home is not carried

over yet to the public places. It took me three days to find

their national state museum and when I entered no one

greeted me. And museum viewing is an experience unlike any

other place. It is dimly lit, cracked and peeling walls, and

at times viewing national gold and silver icons by candle or

flashlight (it happened three times in West Georgia). My

friend Maka Dvalishvili worked several years to create a

collection of museum reproductions of rare Georgian

treasures. She raised the money from outside sources,

designed the objects, began the marketing campaign and then,

a few days before the final official opening, she was told

the national museum, who housed her institution of arts and

culture, would have no electricity so the opening had to be

cancelled. The government would not pay the electric bill

for the museum. It was with tears of joy that she heard that

she could open the exhibition, but with only three days to

get out invitations and prepare. Planning in Georgia is a

daily process and long range plans are a myth or dream of

the future.

Like the image of Janus, Georgia shows many sides. Its love

of the arts is unmatched. I have watched mothers take small

children to the ballet, opera and exhibitions that would

challenge the patience of mature, knowledgeable adults. They

learn dance, music, singing, painting, poetry early in their

education and hold it close for life. The supra, the ancient

toasting to honor and preserve the traditions of Georgia, is

an event at every meal where family and guests gather. Some

drink too much; most doesn’t. The stories of recent courage

and dignity by individual Georgians are too numerous to

relate. Everyone tells you the government is corrupt and new

leadership is needed but the march on Parliament in November

of 2001 was peaceful and orderly. Although the problems are

enormous, the process of becoming a new democracy is moving

forward in fits and spurts but still moving. In Roman times,

the temple of Janus was a symbol of the state of the Empire.

If the gates were closed, the Roman Empire was at peace; if

open, it was in turmoil or war. The gates in Georgia are now

both open for democracy to come in as an honored guest and

closed so that the Georgian traditions can still flower and

grow.

|