|

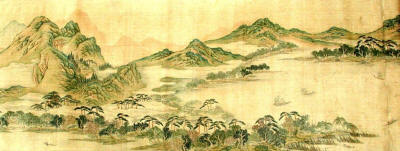

Part Four: The Ribbon of

Mist Comes Downstage

or Drifting Into The

Unknown

"There are ways but THE WAY

is uncharted."

“First you shoot the

arrows and then you paint the targets.”

Statement by a friend at

University of Colorado

“When going outside into

the world, hold hands.”

Robert Fulghum, from

Everything I Need To Know I Learned In Kindergarden

Where have we been? From our ordered, balanced world,

we journeyed into places where we need love and reason to

guide us. While drifting along, like an interlude in a

musical score, we got to know some of our companions, a

little about our self and we fancied who we might like to

take along on this trip as fellow travelers. It was a time

to allow our imaginations to drift too. We left the baggage

of time, job, worries and home behind us. When we left an

island where we had rested, there was sadness on leaving and

excitement about seeing what lay ahead. We were given

shelters where we could reflect on what we had seen and

guess what might come next. Again, the scenery changed

slightly (not enough to shock us but enough to keep our

interest). We saw the mists for the first time and a few

pockets of mists came forward but not enough to engulf the

clarity of our vision. We allowed ourselves the luxury of

drifting.

Orientation: As your guide, I must remind you to

check your knapsack for the essentials of this trip: your

imagination, your vision, your mind and spirit, your

attention to detail, your ability to thin slice, your

inquisitiveness (shared with the others on the trip) and

your memories. OK, if all that is packed, it might be time

to move out into the lake and slowly sail to our next

adventure. But before we do that, we must recognize that

this is a “work of art” (the work is the housing for the

art). The critical word here to examine is “of." The work is

all the details that I have pointed out. The art (the

creative thought-process behind the work) may be hidden at

times. As you saw in the last part of our peace journey, I

am an artist so I can, at certain points in your voyage, put

myself into the skin of this Chinese painter on silk.

Many through history have asked the question, “What is art?”

Some on our trip might say, “It is a painted, hand scroll

landscape.” But that is the “work” that reflects the art

which is the thoughts, emotions, memories, and visions of

the artist. Art is a risk. One never knows where the trip

will lead (although you start with a plan which must change

as time passes). Art is like jumping into a deep lake,

keeping yourself afloat with the actions of your limbs (now

that is “work”) until a boat comes along (an idea or image)

and takes you further along your journey. Art is the

creative imagination in action, seeing a little beyond where

the ordinary viewer sees, and having the courage to move

ahead.

Two Artist Companions: When I was studying Chinese

painting history with Dr. Li at NYU in New York, one of my

fellow students was Alan Kaprow, the artist who gained

international fame with his “happenings”, works of art in

time and space, with a script and ordinary participants.

Where Alan’s happenings led even surprised him sometimes. We

were sitting in a restaurant, sipping, eating and relaxing,

and discussing the difference in how we approached the

unknown. He said that he used everything and I said that I

took some things away until I had the essence of the

creative experience. We both exaggerated (I will not say,

“Lied!” but we did embellish reality). Alan told me how he

learned to go on his trips with the “happening” in a state

of patience (much like Sam did at the poker table and B in

the insurance business): “I love to stand in line, waiting

to go into a theater that is playing something I wish to see

or just stepping into a line to wait with others for no

reason. It teaches me patience.”

As director of an art museum in Waco, Texas, I asked Robert

Wilson (whom I had met in Boston at the opening of three acts

of his Civil Wars (a 17-hour play which was composed for

six continents and was to be brought together for the 1984

Olympics in Los Angeles. It never came together since the

money ran out), opening at the Cambridge Repertory Theater,

and an exhibition of his drawings at the Boston Contemporary

Museum of Art) to create a work of art for his home town,

Waco. Wilson was better known in Paris, France than on the

streets of his birthplace. Houston had recently had him

direct the Houston Opera, a play at the Alley Theater, and

opened a massive exhibition of his work in the Contemporary

Art Museum. Bob is a Renaissance man for the 21st

century. His reply to my request was swift, “I want to

create a twenty-two foot high, core-ten steel (that rusts to

a point, leaving a marvelous patina) door, partly open.”

When he came to see the site, he walked all over the museum

grounds, down the street out of sight, and then returned.

“This place,” he said, “was the home of the Cameron family.

They had owned this whole hill. Their home was called

‘Valley View’ because of the sweeping vista of the Brazos

River and the flat plain to the east. I want to place it

here (pointing the ground), partly open. It will be a open

door to or from nature. I want pathways and walkways around

it so that it can be seen from many points of view.” At that

moment, we made a contract with our handshake. "The Door" has

become a symbol in that region of the country for the “open

imagination” of the artist in all of us. The work of

building “The Door” was done on the West Coast while Bob

opened a play in Sweden and Tokyo, money was moved through

the Parsons Gallery in New York and directed to his Byrd

Hoffmann Foundation (Bird Hoffmann was a dance teacher that

told him to slow down his speech, since he stuttered until

the age of seventeen, and he did with enormous success. At

the same time, he slowed down the world in his art work.)

Robert Wilson is a model for the 21st century

artist who separates making the work from his art (the

creative act of envisioning what it will be).

What have you been doing while we journey along on this

lake, stopping and reflecting on where we have been, and

trying to notice all the details in this water/landscape?

Everyone around me noticed that I carry a notebook and make

sketches and notes in it. As your guide on this trip, I feel

that it is my job to record what I see and make some

decisions on their possible meaning to the whole experience.

Here are two sketches for Part Four:

Rule Six: Your mind is not

a storage unit (although sometimes a tool box and index

sorter). Keep most data in notebooks, computers, libraries

and other places that can be accessed. The notes are mind-

joggers.

It is time to thin slice

our vision again:

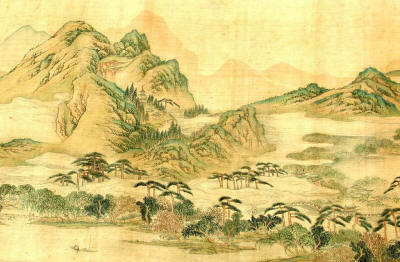

The mist is a ribbon that ties the background to the

foreground, acting as an open backdrop for the arrows of the

Evergreens.

Mountains cluster in rhythms like notes in a lake melody.

The first major Northern Sung mountain is introduced.

Bulrushes and sadness are still our companions.

The numbers: One, two, three, four and six are played

upon.

A many-layered, pointed Pagoda is nestled within the

shelter of guardian, needle fern trees.

On the far left is a major Northern Sung mountain with a

pagoda temple on its right shoulder. As your guide I should

point out that the line of trees at the bottom has taken

over the position of a frame (a job held by the mountains

and hills in Part One at the top of the scene) and they give

a foundation now to our imagination to fill the void. A

ribbon of mist which starts high up on the right side has

snaked its way to the foreground. Now, more is hidden than

revealed. The unknown is more dominant than the known. By

the composition, we are implored to search the space above.

Our bulrushes on the right side lead toward the future but

instead of being at the end of the island they are now at

the beginning. They stand as sentinels of the future. Old

friends are still with us: the Evergreens, the mists, walled

fortresses, boats, islands, hills and the mountains (that

have become massive statements stopping our vision for a

moment so that we are forced to explore them).

We have moved to a landscape where there is more emphasis on

space than substance. The mist is now the nervous system of

the scene and the boats, numbers (2, 3, etc), mountains,

trees are the underlying beat. We are carried along by the

music of the landscape (the water, the mist and the isolated

notes of boats).

The rolling mountains on the right side descend to the boats

like musical notations: two mountains to one peak to boats isolated on

the lake. The mist is the melody. All else is secondary as

an underlying heartbeat.

Art works have traditionally had four elements by which they

were appreciated and judged: usefulness, realism, feeling

and form.

Usefulness: A Ming Dynasty hand scroll is useful in

that it is a work of art that is taken out and exhibited

only on special occasions. In the West, we are used to

exhibitions being held in rooms with each work hanging alone

with enough space around it so that it can breathe. That is

the essence of freedom and democracy. In a Chinese scroll

there is freedom also but it is the freedom of each element

(not the whole) to exist in its own realm, its own space, at

some point in the work. As one artist friend said to me in

Taiwan, “I have the freedom of silence.” The usefulness of

the scroll is its use in the ceremony that surrounds the

meeting of friends in fellowship. The eating and drinking

and viewing are all part of a ritual.

Realism: Most cultures, and China is no exception,

see realism as pertaining to the likeness of things as a

society generally describes them. Realism is

representational (the object or scene represents something

that everyone recognizes as “real." The boats float on the

surface of the lake, the companions stop to reflect when

they become tired and their shelters (huts, temples,

housing, jutting rocks, etc) look like what we expect them

to be. The sky is up; the earth is down; the mists float

over everything; the lake flows around the islands and the

mountains are anchored to the land. We call that “real." We

are comfortable in a seemingly real world (I say seemingly

because you do remember from Part One that there were five

masts shown over only four boats).

Feeling: What we have felt to this point is

contentment in the formal order of the world, ABA; surprise

when this order changed, sadness on leaving someplace where

we had found shelter and a place to reflect, love of certain

objects: colors (green, pink, black and brown), movements

(the serpentine mist), stability (the majestic mountains

wedded to the earth), fellowship with our companions and

wonder in the vastness, and anxiety with the movement toward

the unknown and unknowable. Feeling is not of the mind but

the heart and spirit. It is an important ingredient in

judging a work of art when the meanings are shut behind the

“closed door” of the unconscious.

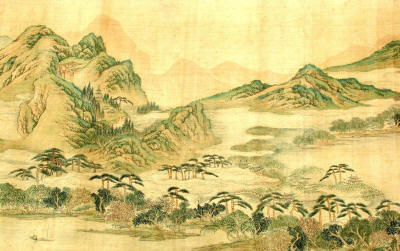

Form: In 20th and 21st century

art, form is the dominant element in seeing what makes up

the work of art. In this hand scroll, your guide can point

out a sequence of numbers starting on the right side of: (2)

two willows, (1) then one willow, (2) evergreens, (3)

evergreens, (4) evergreens, (3) evergreens, (2) shelters,

all leading to (1) great mountain form. The dragon spine

down the side of the mountain leads us to the end of a

ribbon of mist. Below the trees, on the lake, starting to

the right and moving left, (1) boat with (2)masts and (1)

passenger, leading to (1) boat with (3) masts and (2)

passengers. Below those lonely boats on the lake are the

bulrushes leaning to the left where we find (2) shelters

which eventually lead us to the mountain side where (1)

pagoda is flanked by a multitude of sharp-pointing trees

which stand as guardians for the temple with (2) two

isolated trees beside it

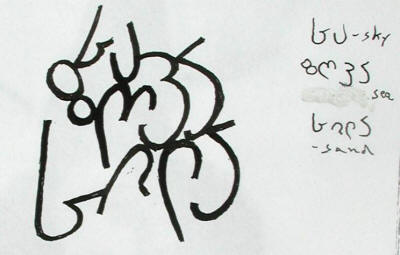

Story of Travel: In 2001, while on a Fulbright

Scholar’s grant to Georgia (Eastern Europe-Russia), I was the artist in residence

for the USA at an International Symposium of Artists

Workshop for a month in a small city 75 miles south of

Tbilisi, Georgia. Every day we worked on our creations,

getting ready for a large exhibition in the middle of

September. One hot day just to rest and relax, a Georgian

friend, his wife and their two children took my wife and I

to the Black Sea for a day at the beach. When you have been

working everyday, it is hard to stop so I decided while I

lounged around I would do some drawing from Georgian writing

(which I loved for the roundness of the form and the way

that it reminded me of Renoir’s women). I asked my host to

write “sky”, “sea” and “sand” in Georgian. He did. I started

to play with the forms, connecting the letters and seeing

how I could make something that was interesting and also

emphasized the fullness of their letter forms. Here is what

I created:

So it is with the forms that I find in this Ming hand

scroll. I want to see how they go together in a way that

pleases me and has a hint of reality to the process. Your

understanding of these forms is less important than your

recognition that there is a sequence and an ordering of

numbers to the simplest of shapes and details.

As we move forward, we see, on the left, two sharp peaks of

mountains with three similar peaks below those. Above are

three hardly visible, faint mountains in the distance,

giving us a sense that this scene is repeated all over the

world where we have water and land pushing to the sky. Below

the major mountain mass, on the lake, we view (1) boat with

(2) passengers and (1) mast that is heading back the way

that we came. It is the first image that goes backwards in

our journey.

Let’s Rest On One Object:

Let’s thin slice the dominant mountain and what it holds.

Pyramid of a mountain with pyramids of rock making up its

shape and form.

Pagoda placed at a golden section juncture; a little to

the right and a little past center up the mountain.

A single evergreen beside the pagoda which is built in

multiple layers.

Clusters of needle-pointed trees standing guard around

the pagoda.

Buildings as visual steps leading us to the pagoda.

One rock beside the pagoda as a thrusting force moving

our eye upward.

And down in the lower right hand corner is a fortress wall

that resembles and symbolizes a bridge for our travels and

our imagination. While all this is going on, the mist is

wrapping itself around every shape, every element and every

solid thing.

Rule Seven: When in a

foreign country, remember that you are the foreigner. The

world outside ourselves is foreign to us but we are what

must adjust, not the environment.

What forms intrigue you? What emotions does this trip

bring to the surface? What do you call “real” and what is

not “real”? Are any of the tools that your guide has given

you helpful (are they of “use”)? Send us your comments.

|