|

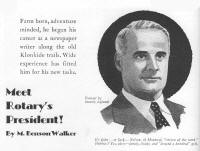

MEET

John Nelson, president of Rotary International! He's John Nelson

on the list of officers and in the Montreal telephone book. But he’s

John ‑ or John

‑to you and me and all those who have ever met him.

And so it infallibly follows that clean across North

America, from Atlantic to Pacific, in Canada, in the United States, and

in Mexico, there are people who are glad that John is on the job. There

are, incidentally, others who feel the same way in China, Japan, Korea,

India, England, Australia, and Europe.

For he has taken in a lot of territory in his time. The

chances are that he will take in a lot more.

His post office address is "Montreal, care of Sun Life

Assurance Company," whose public relations counsel he is. But in

actuality John‑or John‑Nelson's home is somewhat larger than this. Its

diameter, in fact, is something short of 8,ooo miles, and it has three

dimensions. This description, if you are mathematically minded, will at

once call into your imagination a globe approximately the size of the

earth.

That is exactly what it is intended to do. For, if John

Nelson is not a citizen of the earth by training, by personal interest,

by virtue of his association with a business organization which has

branches in forty countries, and because Rotarians of seventy‑five lands

have considered him fit to head Rotary International, then he is not the

man I know.

His first contact with foreign affairs came in 1898 when

he left his Ontario farm home as verdantly green cub reporter for the

Victoria Times which was published on Vancouver Island in British

Columbia.

NOW

this was before the day of the Pacific cable, and the enterprising

newspapers of the Pacific Coast used to maintain steam launches in which

their energetic young men raced to meet incoming ships from Asia and

Australia in order to pick up news of stirring doings from their

passengers and any foreign newspapers which the pursers had saved for

them. The news would then be wired to the other papers over the

continent.

That was when John Nelson first learned the importance of

foreign events, for he was one of the youths who beat the pilot boats to

the liners. As a matter of fact, he must have learned a few other things

as well, for two years later he was the city editor of the paper and in

three years more its managing director.

He was with the Victoria Times for thirteen years,

during the entire colorful period of the Klondike and Nome gold rush

when men streamed northward through Victoria, a few to return rich, many

to come back scurvy‑ridden, frost‑bitten, and broke; some not coming

back at all. It was a great epoch, hardy, virile, and full of drama.

Young John Nelson gloried in the glamour of it.

Then he crossed the Straits of Georgia to the mainland

where he was for five years the managing director of the Vancouver

News‑Advertiser. When he left that job he did so in order to buy the

Vancouver Daily World with two partners. He ran this paper until

he sold out in1921.

After this followed a period of four years of relief from

executive duties during which John Nelson was one of the most prolific

magazine writers Canada ever knew.

"The truth is that I've been smeared with printer's ink

all my life," he says now in talking over those days. "I couldn't get

away from the game."

It was his knowledge of

world affairs, gained during his years of active newspaper work in times

and places full of vivid interest, that made it possible for him to

write articles for some of the most authoritative periodicals of the

United States.

There was, for instance, that first Imperial Press

Conference in 1909 when a group of newspaper men from all parts of

Britain's Empire were invited to London to learn at the heart of the

Empire the problems that were facing its statesmen.

"I had to borrow the money to get to it," he confessed

with a school boyish grin. "But, Lord, it was worth it!"

WHY,

there we met every day in the Foreign Office and the great men of

England came in and

told us what was happening and what was going to. I

remember that they said then that war was coming with Germany‑the very

next year, they feared.

I've never had contacts so valuable and so stimulating."

That was one phase of his training in "world mindedness."

But there were others, too.

Even in Canada, at that time, the East and the West were

almost foreign to each other. Thousands of miles separated them. News

did not circulate. There was no understanding of each other's problems.

One almost might say that there was no unity except in government.

John Nelson was one of the men who realized this, and so,

with some newspaper confrères, he promoted a leased‑wire service

spanning the Dominion from Atlantic to Pacific to link all Canadian

newspaper offices, to facilitate the interchange of news, and to bring

about a national unity that was more than a matter of form. This is now

the Canadian Press, the equivalent in Canada of the Associated Press in

the United States.

Later on he conducted part of a racial survey covering

the entire Pacific Coast from the Mexican boundery to, and including

Alaska. Its purpose was to find out just what were the results of the

impact of the Oriental immigration on Occidental civilization. His

charge was the entire half of the Pacific slope.

"It was an exhaustive study," he admits now. "We took

hundreds of case histories of Chinese, Japanese, and Filipinos who had

come to this continent, and what had happened to them and to their

families. We followed the lives of children born of mixed marriages.”

In making these studies the currents of feeling led

across the Pacific itself, and out of this was born that great

organization now known as the Institute of Pacific Relations, whose

members are the great countries bordering the Pacific, and whose object

is to keep that ocean politically as peaceful as its name.

John Nelson was one of the prime movers of the group that

held its first meeting in Honolulu in 1925, and he later organized the

extremely active Canadian branch of it known as the Canadian Institute

of International Affairs, of which he has ever since been honorary

secretary. |

This achievement is perhaps John Nelson's one boast. He

is proud of the something that he has done to help along the cause of

his fellow man, to promote the feeling of security and peace.

For this is his philosophy as he told it to me. Read:

"We were all one people at one time, a savage people

perhaps. We multiplied and migrated. Some went west and some went east.

Some went south and their skins were sun colored.

"Presently we formed tribes and then nations. Now we have

armies and navies of our own, and we have forgotten or deny that we are

one people.

"Yet in the last generation we have again become one

neighborhood. That is due to science and invention. Now you know at your

breakfast table what has happened half the world away far sooner than

your grandfather knew what happened that night in his neighbor's back

yard.

"Science has done this for us. But science has failed to

do other things. We are paying the price for these failures now. For

science brought into close contact peoples who are not yet educated to

neighborliness ‑people whom even science cannot induce to live together

in peace and harmony.

"Instead, science has put into the hands of both savage

and civilized man weapons so horrible that we are in terror of their

use. It is because governments have recognized this gulf‑this time

lag‑between physical and social progress that they have tried to bridge

it with the League of Nations, with treaties, and with covenants.

"Now I don't believe it's of much avail if MacDonald or

Roosevelt merely sign treaties of friendship. But if you get men of

common interests and occupations, living in different countries,

pledging themselves to a common ideal of peace, then you get something

really valuable.

"In Rotary we have men in seventy‑five countries banded

together in perfectly unselfish union, ‑ pledged to friendship. That

brings war to a personal basis. If you say 'War with Austria,' that

means me that I've got to kill Otto Böehler in Vienna. If you say 'War

with Japan,' means I must kill Yoneyama in Tokyo.

"To Rotarians that is little else than civil war‑for it

is a war with our brethren. For Rotary is mobilizing individual goodwill

around the world. It has, indeed, declared a perpetual moratorium on

ill-will.”

That, by and large, seems a fair statement of belief. It

is the sort of philosophy which will keep the world sane in spite of

politicians who get frightened at bogeys conjured up by gentlemen who

are interested in the profits of war and armaments. It is the sort of

creed of which no Rotarian need ever be ashamed; which every man

believes, even if he cannot put it into words.

There are other points of interest about Nelson.

What are your hobbies,"

I asked. People like to know …"

“My family," he said at

once.

"Good, and what else?",

“Books and golf."

About what do you shoot?"

”Oh‑around a hundred."

I put it down with all the grinding envy of the man who's

lucky if he touches a hundred and twenty.

Behind his desk hangs a picture. It seemed to show a

familiar figure in unfamiliar garb. It took time to recognize exactly

who it was under the eagle‑feather headdress.

"T‑I‑O‑R‑A‑K‑W‑A‑T‑E,"I spelled out carefully the name

that was below it and promptly brought a blush to a hardened Rotarian's

cheek.

"Heap big chief, me," he mumbled embarrassed, though why

a business man should blush at having had an alias conferred upon him by

the honorable remnant of the once great Iroquois Confederacy it is

difficult to say.

"It means 'Bright Sun,"' he explained. "And it happened

three years ago. Furthermore I suspect that the good Mohawk braves who

had the naming of me, paid a kind of compliment to the company for which

I work in choosing that particular name."

Not only the Indians are inclined to compliment the Sun

Life through John Nelson. Rotarians of the Twenty‑eighth District which

includes Quebec, part of Ontario and a large portion of New York State

in its 65 clubs, feel the same way.

For when Jack Nelson was offered the 1929‑30 governorship

of the district he refused it, feeling that the obligations he would

assume might take too much time from his work.

But T. B. Macaulay, president of the Sun Life insisted.

"T. B.," as he is known in Montreal, was very definite in his approval.

"I want my company to be identified," he said, "with

every big thing in the public interest that is happening anywhere."

Later, as the inevitable nomination for the presidency of

International Rotary came along, Arthur B. Wood, managing director of

the company, himself a prominent Rotarian, took just as broadminded a

stand when a committee of leading Rotarians sought his consent.

The result is that when Jack‑or John ‑Nelson took over

the reins of office in Boston, he did so with the knowledge that he

could work whole‑heartedly for the welfare of Rotary and of mankind,

because of the full approval of the principal officers of his company.

And from that point on, my story is known well by all who

have read it thus far.

Published during

President Nelson's Rotary year in The Rotarian, January

1934. Written by M. Benson Walker,

part of the "Meet the President" series. Walker lived in

Montreal, Canada, the home-town of John Nelson, president of Rotary

International. He was the cable editor of the Montreal Daily Star.

Prepared by

Wolfgang Ziegler

31 August 2003

|