|

| HOME | GLOBAL | DISTRICTS | CLUBS | MISSING HISTORIES | PAUL HARRIS | PEACE |

| PRESIDENTS | CONVENTIONS | POST YOUR HISTORY | WOMEN | FOUNDATION | COMMENTS | PHILOSOPHY |

| SEARCH | SUBSCRIPTIONS | JOIN RGHF | EXPLORE RGHF | RGHF QUIZ | RGHF MISSION | |

|

|

|

Joseph L. Kagle, Jr. Peace Essays

|

|

Some loves last a short time and some last a lifetime. So it is with the love that we have for our CARS. We comfort them when the weather is bad with a clean wash on the good days. We say to others, “I love my car. It is the one place where I can find peace of mind on the open road.” It is in this spirit that art has caressed the automobile as an icon of our time, building bigger and better highways, finding new ways to improve the comfort on the inside and restoring our “grandfather cars” to show them off to a new generation of lovers. In Denmark, the artists got together and had one of its members marry her stylish, yet tiny car; Alan Kaprow had Cornell students spread jam over a car and clean it off by eating it and he collected all the tires in New York for a courtyard leading to his new exhibition; Chamberlain took those part of shiny cars after the salvage engineers had crushed them and made sculpture; and another pop artist painted a smiling VW to hang in the galleries of the great museums alongside the other portraits of important characters. Also we can add time exposure to an American Oil Sign and all at once it is interesting for our viewing. The automobile is our round feet that we honor by improving it all the time to go faster, safer, more comfortable and aesthetically enhanced as a loved one which has been transformed into a work of art.

CARS IN ART: The Automobile Icon or Chitty, Chitty, Bang, Pop, and Away We Go

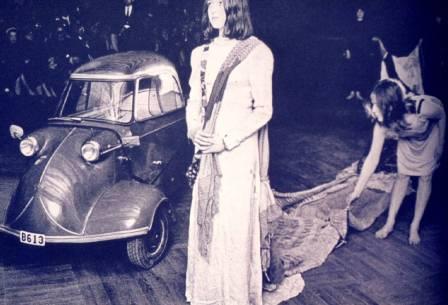

The first image that lingers in the corner of my mind concerning cars in art is the photograph of Rose-Marie Larsson standing beside a small foreign automobile in her wedding dress with train of 180-foot history-of-the-world-in-rags. The bug-like automobile and Rose-Marie were married in the fun-filled solemnity of a happening at the Modern Museum in Stockholm on April 7, 1964. The photograph was reproduced in Allan Kaprow’s Assemblage, Environments, & Happenings.

Kaprow was challenging the whole question of the enduring versus the passing. This theme has been coming up continually since Impressionism challenged the West's deep belief in the stable, clear, and permanent. The stationary and speeding car is both an enduring and a passing symbol for our time, an icon of contemporary life. The car, at times, cannot be separated from the man or woman who directs its motion, from the artist who uses its image.

In early depictions of the car by European artists, such as Andre Derain's London Bridge, 1906, the cars were colored marks in an overall composition, no different than buildings or trees. The artist was interested in nature and natural objects.

At the beginning of the 20th Century, the car was not, in the artist's mind, "natural". Some artists had, since the middle of the nineteenth century, been groping their way toward an art of elemental forces in which the illusion of nature was completely eliminated. Cubism was the intellectual representation of that pursuit of these forces in nature. The scientific method was the artist's tool to break up, the world. One would think that the car, non-natural, man-made object, would have been a choice subject for cubism, but the main subjects continued to be still-life, portrait, and landscape. The Futurists in Italy were interested in motion when they dealt with walking dogs, trains, cyclists, women, faces, bottles in space, walking men, but not cars. Antonio Sant'Elia's project for Citta Nuova, 1919, certainly created a culture around the car with roads, cloverleaves, drive-in buildings, but the cars were shown as black marks between two lines. The car was an object out of the mainstream of the subject matter of art. The car, in its earliest beginnings as shown in art, was a still-life. It was an object in the background, to be driven but not featured.

In 1914, there were young artists creating something new. It was for the apostles of ugliness, The Eight (called the Ash Can School) to take us to the city and begin to feature something unique, the car in art. This brazenness of American artists led to art for democracy's sake instead of art for art sake. Once The Eight tore down the canvas wall of exclusiveness, the image of the street, including the icon of the car, was liberated and proclaimed in brilliant color and the freedom of brushwork. Max Weber's Rush Hour, New York, 1915, was not long in coming. Weber took Picasso's Cubism and Italian Futurism and gave us the traffic jam in New York, with lights flashing, horns blowing, and speed, speed, speed. The car, an unnatural, natural object, was liberated in America. In turn, the car, as much as apple pie, mom, and the flag, became the symbol of America. It liberated the middle class to travel across the country, wherever they wished to go; it liberated the artist to depict the car in many ways; and it liberated itself from a simple machine image to the transformer for good and evil and finally, to the lover long-awaited. The car now has “a life of its own”. It is a conventional icon with a personality.

In America's melting pot of today, what is a car? It is style to show and style to go. It explores the boundaries of nature with good looks, comfort, and versatility. It is called a class act, sleek and sophisticated, a bold look that reflects a sense of good taste, plush, all in fun (in fact, funtastic), the toughest (in fact, a tough act to follow), supercharged, visionary, meticulous, superlative, luxurious, a new generation, power-boosted, flow-thru, dual-stage, clean, solid, electronically-tuned heartbeat of America. It takes the road by storm and racks your brains out, and in seconds you'll forget you bought it for its looks. Inside it, you can dust thy neighbor, be a driver like Jack Nicklaus, and have the perfect reconciliation between love of family and passion for driving. You can predict the future, explore the unexpected, rule the world, buy power, and be wedded to the ultimate driving machine. History will wrap its cloak of approval around you as you ride with giants who espouse "The Best or Nothing". By opening a simple door, you're held in the loving comfort of coachwork designed and handcrafted in Italy by Pininfarina. In the contemporary car, beauty is form and form is function, as you are placed on center stage. Adjust the ambiance. Take your reward. Begin a beautiful relationship. Become part of the new generation. Check the view. Join the totem of Lynx, Cougar, Taurus, Mustang, and Thunderbird. In the flash of 6.6 seconds, you propel yourself into a wide-stance, low-to-the-ground twin-cam 16-valve aero style pocket rocket that turns quick trips into instant excitement and long rides into all-day adventures. Look up in the sky. It's a bird. It's a plane. No, it is super-charged, supercab, super-crafted, super coupe.

It is much more. Built for the human race. Designed to suit your lifestyle. It represents the nine most important words in the United States: "Satisfy the customer, satisfy the customer, and satisfy the customer." The modern car fits like a glove. The car is the essence of the human spirit seeking a reason for living. It is why functional designs are so beautiful...so calming. It is the human eye distinguishing the essential from the non-essential, the aimful from the arbitrary. It is Porsche, Oldsmobile, Ford, Dodge, Nissan, Honda, Chevrolet, Chrysler, Cadillac style. Even the contemporary artist must, if we believe all the commercial mythology, see each break-through, world-class, award-winning car design with wish some degree of excitement. Our cars are lovers with rugged good looks, toughness, endurance...and a great body.

The values behind the icon, the car, are both enduring and passing, history mixed with speed. To see this changing American phenomenon, we need to narrow our focus. We need to envision America, not as a melting pot, but as a stew pot. The artists who use the car in their works of art are as varied as the ingredients in our stew. We cannot extract all the flavors at once; just a few which seem to rise to the surface of our boiling stew. Chitty, chitty, bang...

The car is not just the subject but the object of art, placed up front and center stage. In 1948, Professor Ing, Porsche creates Porsche No. 1, hand-building it in Gmund, Austria and embodying many of the aerodynamic qualities of the pure, functional, timeless elements of what will be termed "Porsche design." In 1976, now conscious that the car is a work of art, a collector's item, the Porsche creators become museum conservators, zinc sheet-metaling all upper and lower body parts. And presently, in 1989, Porsche artists, engineers and designers turn the overall body design into a conceptually pure, Brancusi-esque work of art by adding integrated spoilers. Part of the engine lid itself is turned into a spoiler (something that corrupts the pure functional design but is a practical necessity); lifting automatically when the car reaches 50 mph. It retracts again at 6 mph.

The car is a transformer with love-hate emotions entwined in the consumer/object relationship. Picasso's Baboon and Child, 1950, is a dynamic symbol of this relationship. The child clings to the Darwin-inspired baboon mother. The face of the baboon is created with the front and back of a toy car that seems to speed toward the child with his arms extended in anticipation of a loving embrace and to ward off the on-rushing vehicle. It is certain that the car/baboon/toy/mother will destroy her offspring. The sculpture is filled with love, hate, concreteness, and ambiguity. It is a visual oxymoron. Today, the car has an evolutionary history all its own.

In May 1964, Allan Kaprow creates a happening that deals with the hunting-gathering ritual of the car and the tribe. Women build a nest of saplings and string. Men cover a car with strawberry jam. Women go to the car and lick off the jam while the men destroy the nests with shouts and cursing. Men join the eating ceremony with bread and eat jam with their fingers, slapping the white bread all over the sticky car.

The men and women dance. There are no spectators. The men jack up the car, remove the wheels, set fire to it, sit down to watch, and finally light up cigarettes. All the men remain, eyes upon the smoldering car, until it is burned up. Then, they leave quietly, driving away. As Kaprow remarks, "The line between art and life should be kept as fluid, and perhaps indistinct, as possible."

Earlier and later, John Chamberlain takes parts and other metal from the junkyard and uses these pieces of the car as material for constructionist creations. He resurrects the car into a new, “found-object”, a work of art out of the graveyard of contemporary life. The artwork is made up of the car parts but exists as a statement about something more than the car itself. Chamberlain continues the tradition of Cubism and Hans Hoffmann's breakup of color by giving the assembled car parts new life and new dimensions.

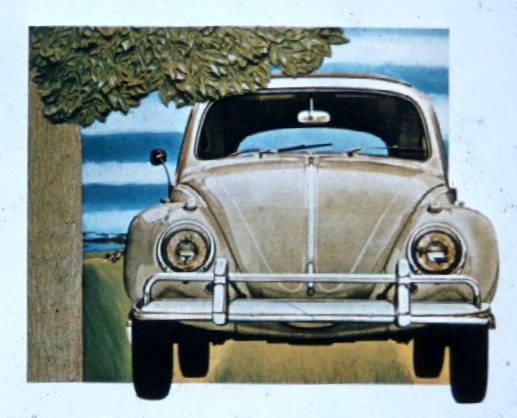

The car can now have its portrait painted by Tom Wesselman. It smiles its Mona Lisa bumper grin and stares out to each of us with its headlight eyes. In return, we place the portrait of the car in our secular temple, the museum, a large democratic, domestic shrine for the whole family. We hold the car portrait close and sacred. It is an act of faith in the power of art. The car takes its place as a legitimate character in the world of art.

In 1968, Rowland Emett, a perky, pink-cheeked Englishman, created eight thingamaboobs for the movie Chitty Chitty Bang Bang and installed The Emett Vintage Car of the Future, dedicated to the Spirit of Future Retrogression, in Chicago's Museum of Science and Industry. Thingmaker Emett is that most insidious of subversives, a spoofer who makes existential sense. He is a fantasticator whose works whirls, spin, make sounds, entertain the child in all of us, and mystify. The Emett Vintage Car of the Future is an individual in a world of clones, a unique personality, a Gaudi-like icon to confront and combat the Porsche. In 1976, an onlooker buttonholed the 70-year-old antic Edison of Wild Goose Cottage and demanded: "But what's the end product?" Emett's considered answer: "To bring the smallest smile to the eye of the beholder." He believes the decline of a society, mirrored in its satire, is the preliminary stage toward a reconstructed society that could become the model for the humanistic world of tomorrow. The celebrity car has arrived.

Pop...

The car is in every aspect of contemporary living. After its birth and legitimizing, the car can take its place in a larger context of the celebrity in the world of art. In fact, it can have its own Hopper-like, lonely environment. Ed Ruscha can create a painting around the special environment for the car, The Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas, 1963, without depicting one automobile. Even so, the specter of the car is present.

George Segal makes the service station stop more real than the mummies who people this space. He creates the bus as a tangible thing which houses plaster mannequins. Andy Warhol takes Chamberlain's twisted metal automobiles and parts and, through the repetition of a crashed vehicle, makes a haunting, emotionless work of pattern and form in Five Deaths Eleven Times in Orange (Orange Car Crash), 1964) . Robert Este reflects the modern city in the car's curved mirror surface.

Robert Rauschenberg combines the car, its environment, its parts, the road, an aerial view of highways, and the process of representing the automobile in one synergetic statement.

At the 1988 Carnegie International Exhibition, 4 Cars by David Fischli and David Weiss, created in plaster, are four non-emotional, cubed works of art that place the car on a pedestal. Individual artistic identity is forsaken to feature the car as a classic icon and an everlasting symbol.

And away we go.

In the late 20th Century, the car has found an identity. It has been lionized. Artists use it in their works as a natural icon of our times. The viewer sees it as more than a work of art. The viewer has, if he realizes it or not, mirrored the commercial where a consumer is shown in an art gallery, viewing a car on the wall. His hand tentatively reaches out and opens the car door. He looks around. No one is observing his actions. Therefore, he defies gravity by pulling himself into the car. Suddenly, he drives away across the wall, only leaving car tracks, just before an older, obviously traditional, viewer comes in stage left and marvels, wide-eyed, that the car is gone.

If we push the nineteenth-century search for a symbol of universal proportions to its twentieth century solution, we can make a case for the car being that symbol. It has been ritualized by Kaprow and given multiple identities by artists of many styles. The nineteenth-century search for an icon that rivaled nature is now with us, a man-made icon, the car. Nissan's Infiniti is shown by the heralds of advertising through images that are haunting in a Zen-like way: unmoving snow scenes with a group of trees on the far left corner with only the slow, constantly changing clouds in a gray sky; a crackling fire on an open, human-free beach that gives us eternity through change; and the stationary monolithic rocks high against an open, free sky, that compare the car to the rocks at Ryoanji Temple in Kyoto and Stonehenge in England. We are meant to forget that what is being sold is a car.

We have stepped into the vastness of the universe. We can now Eclipse the real eclipse. The object that propels us through space had been elevated to the position of more than subject matter in a work of art. Genre car has become super car, a divine normal, an icon rose to symbolic proportion.

Our cultural stew had been given its required time to cook. We can taste the whole and savor individual ingredients but the stew is so close to our lives that it is difficult to see or envision a time when the car was not with us. Luckily, a museum is an alive place, where data can be stored upon the walls, catalogued into units that can be studied and internalized for each viewer. An exhibit of cars in art is an opportunity to see parts of our artistic stew for ourselves and evaluate the car's impact on contemporary life.

The car has flowed into our lives. It has certain syrup, as Gertrude Stein once said, but it does not pour easily. A consumer has to work to see its influence. Today, maybe all of us: the artist, the viewer, and the consumer are as married to our cars as Rose-Marie Larsson was in Stockholm. Now, though, the spokesperson at the marriage ceremony will not say, "I now pronounce you..." but "We build excitement."

|

| RGHF peace historian Joseph L. Kagle, Jr., 2 September 2006 |